Yikes: According to the Los Angeles Times:

Yikes: According to the Los Angeles Times:

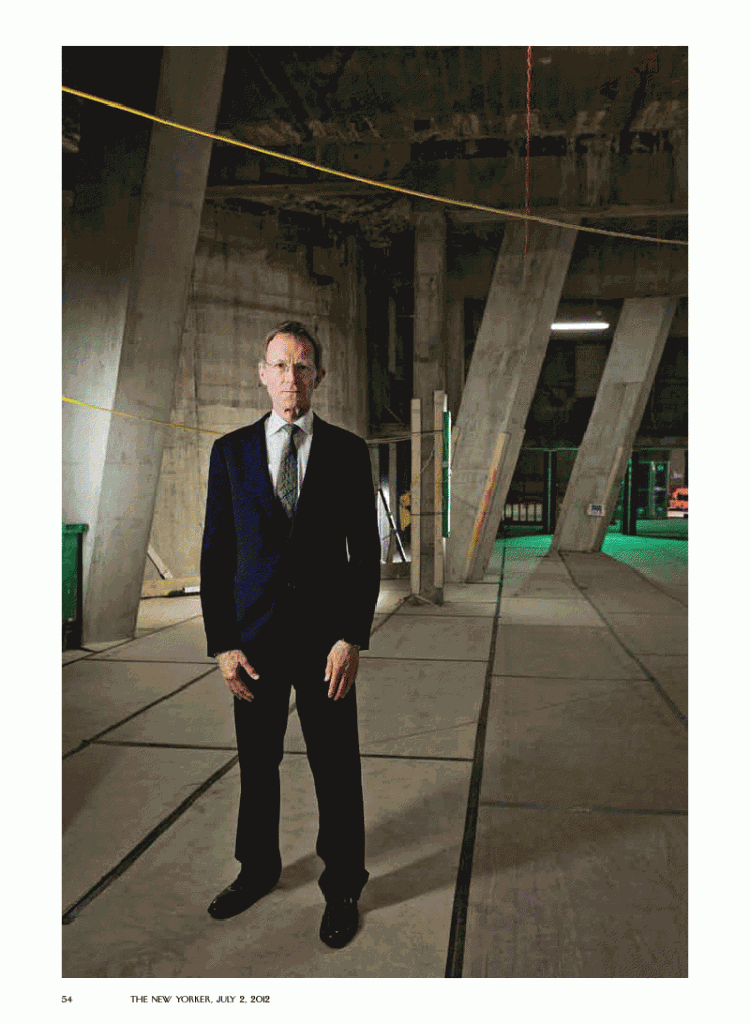

Paul Schimmel, the longtime chief curator at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art and one of the most prominent museum curators in the United States, was fired Wednesday.

The firing was made by the museum’s board of trustees and is effective immediately….

Here’s the link to more, though there’s not much.

UPDATE: And here’s the story that came later, which noted that he disagreed often with director Jeffrey Deitch and said:

Schimmel, who headed the MOCA curatorial staff for 22 years, was let go Wednesday after a vote of the museum board. According to several sources, he was summoned to the office of billionaire art collector and philanthropist Eli Broad, MOCA’s top funder, and told of the board’s decision.

Schimmel is indeed one of the best-known contemporary curators in the U.S., and I would add one of the most respected. Â We await the details. Not surprisingly, there’s nothing on the museum’s website.

UPDATE2: Here are Paul’s parting words:

Dear friends and colleagues,

For once I’ve decided to try and post something of some consequence, rather than pictures of dogs and children. I want to talk about my last day as Chief Curator of MOCA. It has been an extraordinary, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to have been part of this museum. I have counted each day of my 22 years at MOCA as truly special, and the work of helping to define a gro…wing institution and identify a rapidly changing community of artists, both here in Los Angeles and internationally, has been both a great pleasure and a great privilege.Working at MOCA has meant working with exceptional people, first and foremost the artists with whom I have collaborated over the years and who have made me the curator I am today. There are so many of you out there—artists, museum professionals, dealers, collectors, and patrons—who have meant a great deal to me and to the success that I’ve had at MOCA. And to all of you within the family of MOCA itself, I have found enormous support and opportunity—one that I can’t imagine could have been any better, or will be any better anywhere else. My colleagues in the Curatorial Department, many of whom have gone on to other wonderful opportunities, are extraordinarily dedicated people who have done some of their best work here. And the catalogs that we have produced with our publications department are not only great contributions to art historical scholarship, but testaments to the legacy and longevity of MOCA’s outstanding exhibitions.I extend my profound thanks to all MOCA staff past and present, including Richard Koshalek for having brought me to MOCA, as well as to former director Jeremy Strick, all of whom have made the important happen again and again through the years. These colleagues were driven as much by a passion for art and artists as for a desire for MOCA’s individual successes. Together, we have striven to make our shows not just good, not just great, but the best that artists and curators could ever achieve. I also want to recognize the many trustees and patrons how have supported MOCA over the years. Again and again, individuals have stood up to make important contributions to the museum, whether for the success of an exhibition or for the acquisition of a major work into our collection. I know that these last few years of financial crisis have been difficult ones, and I can’t tell you how much I appreciate your perseverance and dedication; when you love something, you love it unconditionally.I am so grateful that even during these last years that MOCA has been able to realize so many important exhibitions that it had long been committed to—“William Leavitt,†“Suprasensorial,†“Amanda Ross Ho,†“Ends of the Earth,†and the upcoming “Blues for Smoke†exhibition, as well as my exhibition “Destroying the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949-1962.†After over 20 years, I feel such pride and honor to have been the Chief Curator at MOCA, and I hope that for the next 20 years, MOCA’s staff and trustees can feel the same sense of privilege and accomplishment that I have.With love,

Paul

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the LA Times