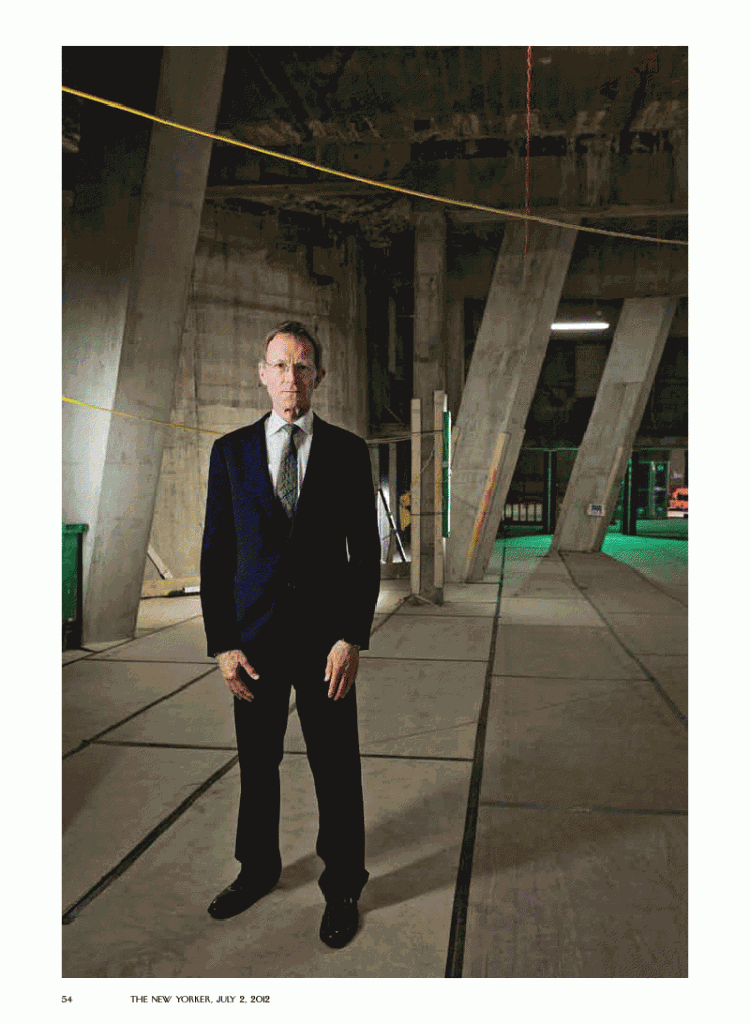

Calvin Tomkins profiles Nicholas Serota, longtime head of the Tate Gallery (-ies, really), in this week’s New Yorker, and it’s largely laudatory, as one might expect. Tomkins doesn’t shy away from saying, straightaway and approvingly, that

ÂSerota has Âbeen Âwidely Âacclaimed— and Âoften Âviliï¬ed—for changing Âthe Âculture of Great Britain. The establishment, the press, and the numberless upright citizens who used to regard modern art as a joke, a foreign-born absurdity practiced by incompetents or charlatans, now embrace it with almost unseemly fervor. Tate Modern, the Tate’s new building for twentieth- and twenty-first-century art, which opened in 2000 in a derelict power station on the south side of the Thames, draws about five million visitors a year, making it the world’s most heavily attended modern-art museum.

Tompkins chronicles Serota’s rise to these heights, changing from an economics major at Cambridge to art history; running Whitechapel Gallery in the East End; co-organizing shows like “A ÂNew Spirit ÂinÂPainting,â€Â at Âthe ÂRoyal ÂAcademy in 1981, with Âwork by the likes of deKooning, Bacon and Richter; inviting artists into the galleries during his first days at the Tate; raising private money for the Tate Modern; etc., etc. It’s not a puff piece, but you know exactly where Tomkins stands.

I’m fine with that. Serota has done marvelous things for art in London. What makes me worry a little is signaled in the headline and deck: “The Modern Man: How the Tate Gallery’s Nicholas Serota is reinventing the museum.” Those definite articles imply that his way is it — he’s leading everyone else to the museum of the future.

If so, various revealing sentences comes as early as the first column. Describing the scene inside the Tate Modern, Tomkins writes about its visitors:

They drifted around in pairs or small groups—hardly anyone was alone—chatting convivially, taking pictures of one another with their smartphones, pausing now and then to look at a work of art. [Boldface mine]

This theme continues in later passages, all challenging the definition of a museum. Examples:

We have many more people than we’d anticipated who want to hear lectures and ask questions, or just spend time here, looking at art, buying Âa Âbook, having coffee with a friend….

For students and young Londoners in their twenties or thirties, the members’ room at Tate Modern is one of the cooler places to hang out on Friday and Saturday evenings, when the museum stays open until 10 P.M. The museum as a social environment, where people interact with art and with one another on their own terms, and create their own experiences, might seem to work against the close study of individual works that Serota learned from Michael Jaffe, at Cambridge. “One criticism of this building is that you can’t have an intimate experience with Âa Âwork of art,†Serota conceded. “That’s something we are going to address in the new building, where we’ll have some smaller galleries, for photographs and modestly scaled works. But, if you come here at ten or eleven on a Âweekday morning, you can still have that experience.â€

Later, Tomkins gives his blessing, by quoting an impeccable source:

John Elderï¬eld, the greatly respected, British-born scholar who recently joined the Gagosian Gallery after many years at MOMA, believes that what’s happened at Tate Modern is “a really radical change in howpeople use museums now. It’s not only about looking closely at works of art; it’s moving around within a Âsort of cultural spectacle.ÂI Âhave friends who think this is the end of civilization, but a lot more people are going to be in the presence of art, and some of them will look at things and be transported by them.†[Boldface mine.]

Hmmm. Does really matter if a lot more people are in the presence of art if they’re not paying attention? No one can predict how big, or small, that “some” will be.

There has to be more than one way to run a museum: Serota has a formula, and a good one, but it’s not the only one.

Here’s the link to the article, though I believe it’s behind a pay wall.

UPDATE: I’ve made a PDF of the article — NewYorker-Serota.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the New Yorker