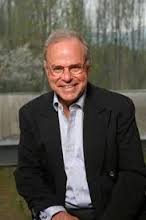

And it’s Matthew Teitelbaum, currently director of the Art Gallery of Ontario.

And it’s Matthew Teitelbaum, currently director of the Art Gallery of Ontario.

If you read yesterday’s post here, you’ll know that’s one down–of many museum director jobs open along the East coast–and many more to come.

In fact, I hear that another I mentioned yesterday will be announcing in the next week, or ten days.

Meanwhile, back to Teitelbaum:

Teitelbaum was appointed Director of the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in 1998 after having first joined the museum in 1993 as Chief Curator. With a vision to transform the Gallery into an institution of global stature serving a vibrant city and region, Teitelbaum significantly grew the museum’s collections, broadened its audiences, increased its research initiatives, and raised its standing to unprecedented levels. Starting in 2002, Teitelbaum spearheaded a major expansion and renovation of the museum, realized by Toronto-born architect Frank Gehry, which encompassed a 47 percent increase in gallery and exhibition space and a complete refurbishment of its existing beaux arts building. Teitelbaum was instrumental in securing a landmark $100 million (CAD) gift from collector and business leader Ken Thomson to complete the museum’s $306 million campaign—surpassing its original $276 million goal. The campaign also funded endowments for operations and contemporary art acquisitions.

I have spoken with Teitelbaum, but not lately, and I don’t have anything to add about his appointment now.