The news I foreshadowed here on Aug. 15 has come true.

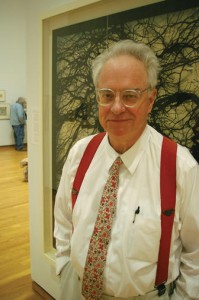

Jeffrey Hamburger, the Harvard professor behind the petition, now more than a year-old, asking Prussian authorities to reconsider their plan to mothball half of Berlin’s collection of Old Masters so they could place a modern art collection in the Gemaldegalerie (pictured at right), their current home, is declaring victory.

And, true, the Old Master paintings will not move from their current location. The Foundation of Prussian Cultural Heritage has done what one German newspaper called a U-turn, admitting that its original plan, to build a separate museum for the paintings on Museum Island near the Bode Museum, which is home to Old Master sculpture, is too expensive and will not take place. It would have cost 375 million euros.

And, true, the Old Master paintings will not move from their current location. The Foundation of Prussian Cultural Heritage has done what one German newspaper called a U-turn, admitting that its original plan, to build a separate museum for the paintings on Museum Island near the Bode Museum, which is home to Old Master sculpture, is too expensive and will not take place. It would have cost 375 million euros.

That is what many of us petitioners feared — that the Old Master put in storage while the new building came into being would last a very long time, possibly indefinitely. Some never wanted the Old Masters to leave the Gemaldegalerie, period, but I was not among them. Nor was I among those who felt any delay in returning them to view — even an indefinite one — was worth it to have the Old Master paintings close to the Old Master sculpture on Museum Island.

So here’s where we are now: In a press release issued about the feasibility study they ordered because of the petition, the Foundation admits that simultaneously placing the modern art in the Gemaldegalerie in the Culture Forum AND relocating the Old Masters to Museum Island is not financially feasible. Therefore, it will now make plans to build a museum for the modern collection at the Culture Forum on Sigismundstraße. It will have 106,500 sq. ft. and cost 130 million euros.

The board of trustees and Parliament must still approve this new plan. The board next meets in December.

Many thanks to a reader in Germany, Wolfgang Gülcker, for sending me the official news.