I haven’t yet managed to get myself to Los Angeles and environs for Pacific Standard Time, so I was pleased to receive an email offering a chance, via videos, to see some of the happenings that took place a few days ago, during the “Pacific Standard Time Performance and Public Art Festival.” There is now a YouTube channel for these events.

I haven’t yet managed to get myself to Los Angeles and environs for Pacific Standard Time, so I was pleased to receive an email offering a chance, via videos, to see some of the happenings that took place a few days ago, during the “Pacific Standard Time Performance and Public Art Festival.” There is now a YouTube channel for these events.

Here’s the link.Â

Here’s the link.Â

As of this writing, 14 videos have been uploaded, documenting the 11-day romp, which included contemporary re-enactments of some iconic works. Among them are John White’s restaging of his 1971 performance piece “Preparation F,” featuring players from the Pomona College football team exploring issues of masculinity and gender; Judy Chicago’s “A Butterfly for Pomona,” a new pyrotechnic performance on the Pomona College football field inspired by one of her earlier works; and James Turrell’s recreation of his 1971 “Burning Bridges,” a performance utilizing highway flares, plus pieces by Suzanne Lacy, Robert Wilhite and others.

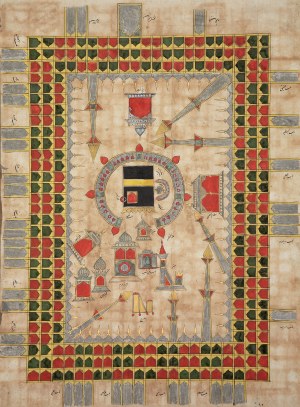

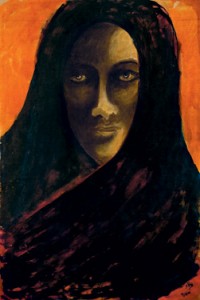

I’m not much of a video-on-the-computer watcher, but these are short — just a few minutes each — and sometimes entertaining. So far, I like Judy Chicago’s “A Butterfly for Pomona” and Lita Alburquerque’s “Spine of the Earth” best (at right). But the most popular one, so far, is Chicago’s “Sublime Environments” (top left).

More may be added — the press reps say. It’s not clear yet. Â UPDATE: Four more videos were just added, including “Three Weeks in January” by Suzanne Lacy and “The Ball of Artists at the Greystone Mansion.”

I can hear groans — is this art? With Performa now an expected part of the visual arts scene, I don’t see how one can deny that it is, however ephemeral.

But I will give the last word to Lucas Samaras, who was part of the happenings scene that begain in 1959 in New York. As he recently told The New York Times:

It was a short period, and it was terrific. It was like you had a tribe, a group of entertainers going from village to village with a tambourine. But then you get to a point where you say, “I’m not getting enough out of this.†Everything has a beginning, middle and end, even if you don’t want it to.

Photo Credits: Courtesy Arrested Development (top) and USC Annenberg School (bottom)Â