A change of pace — no complaints today, just a congratulatory shout-out to the Menil Collection. On Saturday, Sept. 22, the Menil will formally celebrate its 25th anniversary. The date occasioned several efforts, none earth-shaking or innovative, but all an effort to reach out to people who will appreciate a museum that was started and conceived by Dominique de Menil as a quiet “place apart†for contemplating art. (Would that her view were prevelant today.) As you will all remember, Renzo Piano designed it, his first U.S. museum, and one that remains his best. Â

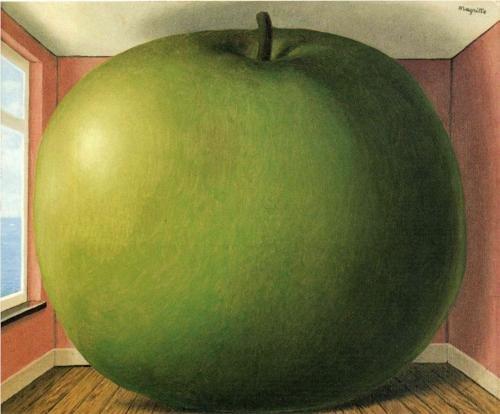

First, as ever to me, are the exhibitions. How can you not love one called Silence? Opened in July, it contains  32 paintings (including Magritte’s The Listening Room, at right), sculptures, performances, and sound and video works, and they aim to “explore spiritual, existential, and political aspects of the absence of noise or speech.”

First, as ever to me, are the exhibitions. How can you not love one called Silence? Opened in July, it contains  32 paintings (including Magritte’s The Listening Room, at right), sculptures, performances, and sound and video works, and they aim to “explore spiritual, existential, and political aspects of the absence of noise or speech.”

Nearby, the Menil remembers its history, with an archival exhibition called Dear John and Dominque: Letters And Drawings from the Menil Archives. They were sent by friends, artists, curators, and others, and the Menil is turning a gallery into a readin room so that people may have peek.

Second, the celebration on the lawn. It’s free, includes music, dancing, a scavenger hunt and birthday cake.

Before and after that date, there’ll be concerts by the likes of Yo-yo Ma and lectures by, say, Calvin Tomkins. Plus a cell-phone walk through the complex.

It’s solid, not-flashy but appropriate, perfect for the Menil. Â

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Menil Collection