That depends on how you measure success.

That depends on how you measure success.

There was a lot of doubt and even some worry that TEFAF, the world’s best art fair, would not be able to make a go of it here in New York, or that if it did somehow do that, the main fair in Maastricht would suffer. After two years in New York–both spring for modern art and fall for Old Masters and 19th Century art, with antiquities showing up in both–the doubters seem to be quiet, at least on one level

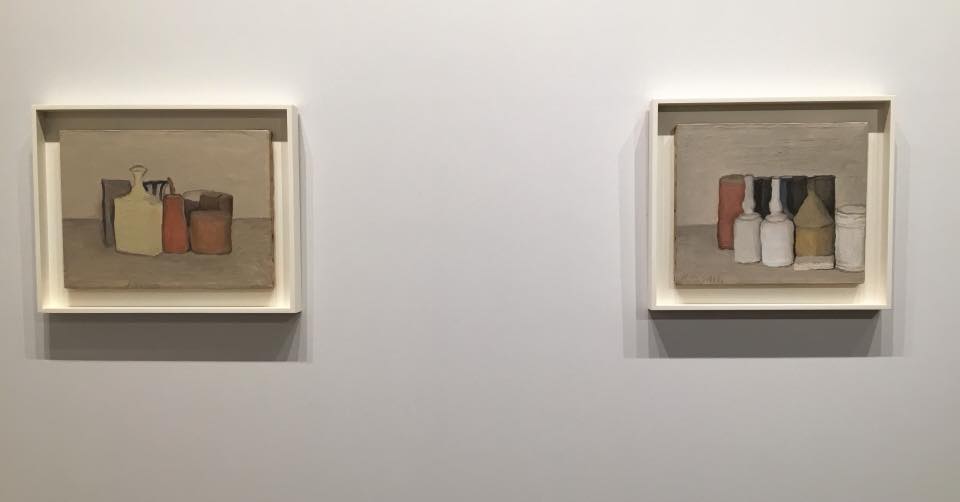

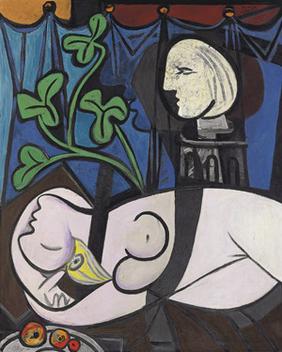

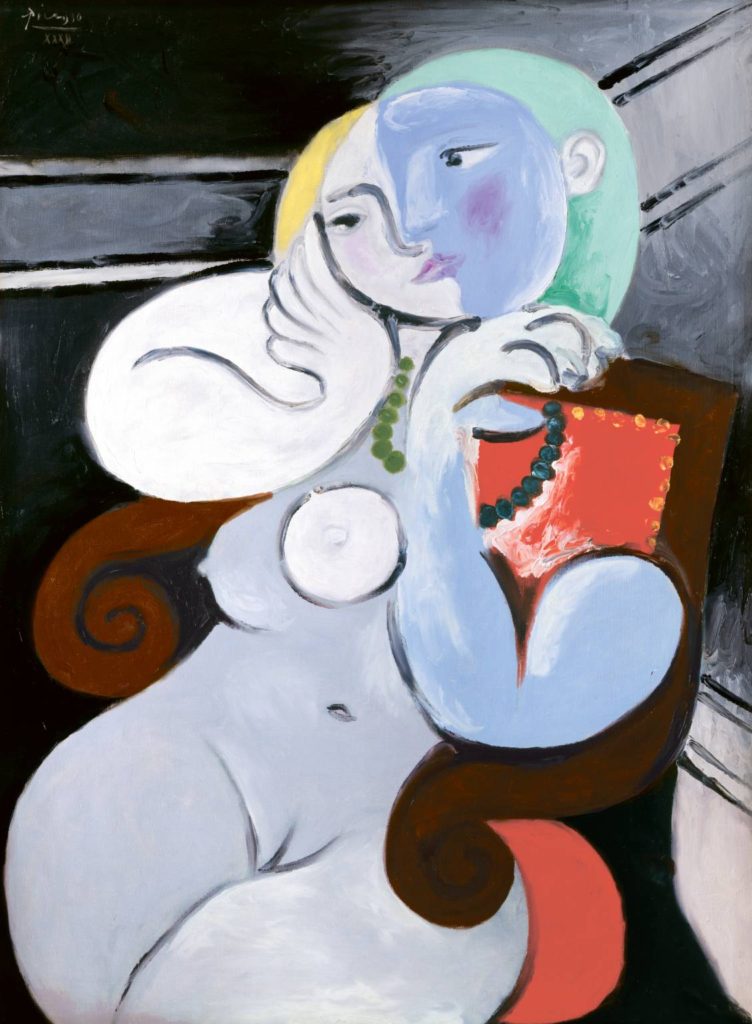

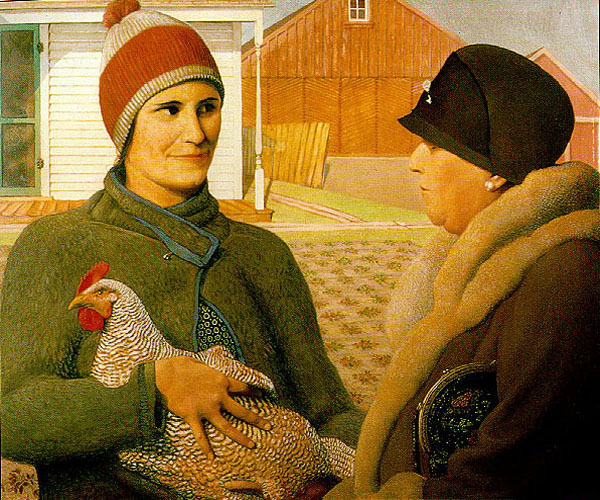

The high quality of art on display at the Park Avenue Armory this week (and through Tuesday, in case you have not yet been and can go) is the reason. While some dealers who had booths last year were shut out for this edition–24 of the 90 participants are new–and they complained, visitors benefited because the art on view really was of a higher caliber. My favorite booth was Wildenstein’s–which offered several Bonnards, and only Bonnards. David Zwirner had an excellent booth, too, matching works by Josef Albers with a wall of Morandis.

Those two stood out in part because they had a narrow range of work that left a big impression–but I didn’t see a “bad” booth in the entire Park Avenue Armory and virtually every one had something fantastic.

So, for fair visitors, TEFAF New York Spring is a big win. Likewise, TEFAF New York Fall.

So, for fair visitors, TEFAF New York Spring is a big win. Likewise, TEFAF New York Fall.

It’s unclear how much is being sold, however–though I did see several red dots on the VIP day and some more on Friday, when I returned.

UPDATE: A press release issues on 5/6 said sales in the first two days were “significant” across the fair and cited several examples, including a Guston painting that went for $5.5 million and a Basquiat for about $5 million.

It’s also unclear if TEFAF is breaking even or making a profit. Though TEFAF itself doesn’t shoot for profits, its partner here in New York, Artvest, does aim to make money. And they are trying–in addition to the prominent new dealers in the mix, there are more partners and sponsors, there’s a bigger cultural panel program this year in an attempt to draw visitors, and they introduced the TEFAF Art Market report with a new focus on art financing. (At the moment it has not been uploaded to the TEFAF website, so I can’t tell you what it said. UPDATE, 5/6–it is now posted, and I’ll look when I have a moment.)

As for TEFAF Maastricht, I didn’t notice any falloff in quality this year, and contrary to rumors, the fair is not leaving Maastricht–it recently signed a 10-year agreement with the city to stay.

For art-lovers here in New York and visitors who can attend here, TEFAF New York is a huge success.

I’m posting a few pictures–a Matisse from Acquavella, a Bonnard from Wildenstein, two Morandis at Zwirner.