If you read my last post, about thematic exhibition cooperation among museums, you know I was in Santa Fe recently. But why was I in Santa Fe–that’s another story, one that resulted in a review published in The Wall Street Journal last Thursday. It was about an exhibition at the Wheelwright Museum of the American In dian titled Connoisseurship and Good Pie: Ted Coe and Collecting Native Art.

dian titled Connoisseurship and Good Pie: Ted Coe and Collecting Native Art.

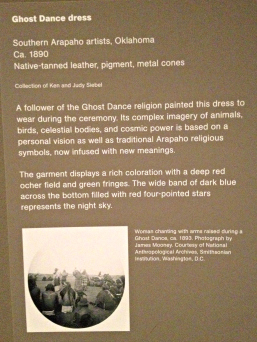

I liked the contents of the exhibition: Coe, educated as an art historian of European art who once worked with the great Sir John Pope-Hennesy, trained his eye by traveling all over the country to see Indian art and visit with native American artists. He collected across all of North America, buying pieces from the 18th century to the 21st century. And he clearly had a good eye to begin with.

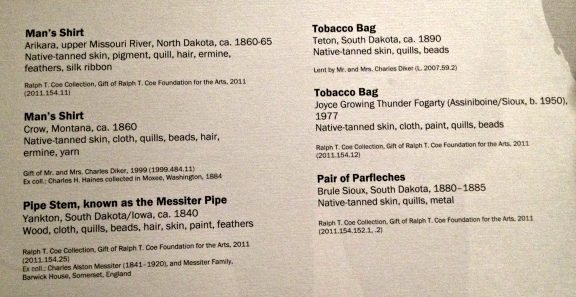

But this is a lesson in display, too. The organizers, including the Ralph T. Coe Foundation and the Wheelwright, didn’t do the material justice. I think the fault lies with both parties. For one, the space (nicely shaped as an eight-sided hogan) is pretty small for 200 objects. That meant there was no room for labels–other than tombstones–for any of the objects, even the very best and most rare objects. So visitors will (I hope) appreciate the aesthetics of the pieces but take away little knowledge about them.

Second, but less troubling, the placement of the art works seemed very arbitrary. After an introduction to Coe, the man, the curators organized the layout around three past exhibition themes, and followed that with a section on Coe’s long-standing friendship with a renowned artist (Joyce Growing Thunder Fogarty) and her family. Â The objects, by and large, were not in those exhibitions and themes did not come through.

Finally, and this seemed very odd to me though I did not have room to deal with it in my review, that introduction to Coe included specimens he had collected of other so-called native, or primitive, art. So the first things a visitors sees is not the Native American art of the title, but rather art from India, Papua New Guinea, Japan, Ivory Coast, Benin, China, Zaire and the Solomon Islands.

Finally, and this seemed very odd to me though I did not have room to deal with it in my review, that introduction to Coe included specimens he had collected of other so-called native, or primitive, art. So the first things a visitors sees is not the Native American art of the title, but rather art from India, Papua New Guinea, Japan, Ivory Coast, Benin, China, Zaire and the Solomon Islands.

Considering that Native Americans rightly take exception to having their art lumped in with categories that bear no relation, I found it odd that an exhibition devoted to a man that pushed so hard to have Indian art recognized for its aesthetics would start off on such a wrong foot.

If you are in Santa Fe, my advice is simply to visit the Wheelwright and enjoy the show. Perhaps the two examples–above, an Omaha (attributed) child’s vest (c. 1880), probably intended for a boy chief, and at right, Crow Indian Maggie Pickett–Yellowtail (1894–1956)’s moccasins and leggings (c. 1945).

Here’s link to my review on my website and here’s one to the WSJ version (which I had to shorten).

The displays themselves are a jumble; the objects are not arranged

The displays themselves are a jumble; the objects are not arranged