Paul Cezanne said that. He also said that Delacroix’s palette was “the most beautiful” in France.

That headline is the end of a short video made by the National Gallery in London; that sentence is the pitch to it. Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art is currently on view at the NG, and one aspect of Delacroix’s impact on other artists and modern art stems from his theories on color.

That headline is the end of a short video made by the National Gallery in London; that sentence is the pitch to it. Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art is currently on view at the NG, and one aspect of Delacroix’s impact on other artists and modern art stems from his theories on color.

So the NG asked Professor Paul Smith to made a video and explores Delacroix’s theories on color and how his approach had a profound influence on the artists associated with the rise of modern art. You can see it here.

It’s a good, no-frills video and I wonder if it would resonate here in the U.S. Yet I found it, and other NG videos to be more informative than some here in the U.S. Here, for example, is the introduction to the exhibition and here’s a “tour” of it.

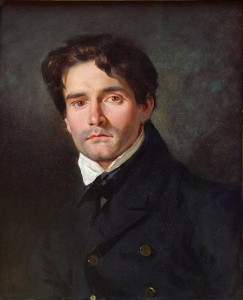

That’s Delacroix in a portrait by Léon Riesener at right.