How did we (I)Â miss this? The National Gallery of Art in late January re-opened its 19th century French art galleries after a two-year renovation, with a new installation that is somewhat non-traditional. (Just as others have, here and here, for example.)

I haven’t seen it yet, but the Washington Post review suggests that it has some idiosynchracies. For one, paintings by Caspar David Friedrich, Thomas Cole and Frederic Edwin Church have been thrown into the mix. Last I checked… they weren’t French.

I haven’t seen it yet, but the Washington Post review suggests that it has some idiosynchracies. For one, paintings by Caspar David Friedrich, Thomas Cole and Frederic Edwin Church have been thrown into the mix. Last I checked… they weren’t French.

The goal, as ever, is to present a showing that people will understand better than a traditional art-historical hang — which nowadays means “do not stick to chronology.” Sometimes, that’s helpful;Â sometimes, it’s confusing, imho.

But thematic presentations are the new norm, I think.

Here’s how the NGA describes its work in a press release:

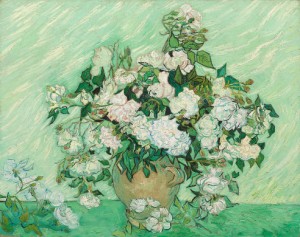

The new installation is organized into thematic, monographic, and art historical groupings. The “new” Paris of the Second Empire and the Third Republic are highlighted through cityscapes by Manet, Renoir, and Pissarro. Showcasing sun-dappled landscapes and scenes of suburban leisure, a gallery of “high impressionism” masterpieces of the 1870s is prominently located off the East Sculpture Hall, including such beloved works as Monet’s The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil (1880) and Renoir’s Girl with a Hoop (1885). A gallery is devoted to the sophisticated color experiments of late Monet, while Cézanne’s genius in landscape, still-life, and figure painting is explored in another. Paintings exemplifying the bold innovations of Van Gogh and Gauguin are displayed along with Degas’ later, experimental works in one gallery, followed by a room of canvases by artists such as Delacroix, Renoir, and Matisse celebrating exoticism and the sensual use of color and paint handling. The final gallery is dedicated to the Parisian avant-garde circa 1900: Toulouse-Lautrec, Modigliani, Rousseau, and early Picasso.

One good thing: the NGA has taken works from the “Small French Paintings” galleries in the East Building, which displayed donations from Ailsa Mellon Bruce, and intergrated them into the new installation in the West Building.

The Post, however, gives us a better idea of what’s different. Mary Morton, curator of French painting, took “an eclectic approach.” To pull in those German and American landscapes, she organized a room around one of the “ideas prevalent in France,” rather than nationality — painting outside. She includes many Mary Cassatts in the hang, but that’s not unprecedented. And as critic Philip Kennicott writes:

The Post, however, gives us a better idea of what’s different. Mary Morton, curator of French painting, took “an eclectic approach.” To pull in those German and American landscapes, she organized a room around one of the “ideas prevalent in France,” rather than nationality — painting outside. She includes many Mary Cassatts in the hang, but that’s not unprecedented. And as critic Philip Kennicott writes:

Ever so gingerly, Morton has introduced small thematic explanations for several rooms: One is devoted to “Exoticism,†another to “A Literary Approach†and yet another to “Bohemian Paris,†blurring some of the “isms†and standard family trees that are old shorthand for understanding the 19th century. Although the use of text to explain groupings of art is standard in most museums and common at temporary exhibitions at the National Gallery, its use in the permanent collection (with the exception of handout material) is rare enough to be a novelty. Â

She also lets the 19th century continue into the 20th, with a final room containing Picasso’s “Family of Saltimbanques†from 1905 and paintings by Amedeo Modigliani.Â

Kennicott says it works, and I will trust him on that for now, until I see it myself. And with gorgeous paintings in the galleries like the two here, van Gogh’s Roses and Manet’s Railway, who could complain anyway?  Read more here.

Photo credits: Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art

Hence this post. The attribution research movement, if I may call it that, fascinates me. It began decades ago, and by now should have had a far bigger impact on museums.Â

Hence this post. The attribution research movement, if I may call it that, fascinates me. It began decades ago, and by now should have had a far bigger impact on museums.