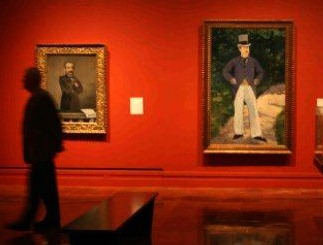

What precisely did the Metropolitan Museum of Art* deaccession the other day? Apparently, a painting far more valuable than the museum had expected — and perhaps one with incorrect attribition.

The Met had decided to sell sixteen Old Masters paintings to benefit its acquisitions fund, and sent them to Sotheby’s, which put them in last Wednesday’s Old Master paintings auction. At the end, as Sotheby’s wrote in its press release, the Met had “achieved strong results, totalling $2.4 million.”

The Met had decided to sell sixteen Old Masters paintings to benefit its acquisitions fund, and sent them to Sotheby’s, which put them in last Wednesday’s Old Master paintings auction. At the end, as Sotheby’s wrote in its press release, the Met had “achieved strong results, totalling $2.4 million.”

Everyone’s eyes were on one lot in particular, labeled “Portrait of a young girl, possibly Clara Serena Rubens by a Follower of Peter Paul Rubens.” During the sale, five or six bidder competed for the work, witnesses there told me. Against a presale estimate of $20,000 to $30,000, it sold for $626,500, including the buyer’s premium.

It’s a small painting, just 14 by 10 1/4 in., but with a long history. You can read the whole description here. It has an good exhibition history (long), figures in much literature, and has this catalogue note:

The sitter of this portrait resembles the younger subject of a similarly informal portrait by Rubens in the collections of the Princes of Liechtenstein in Vaduz. She also closely resembles the sitter in a drawing by Rubens, now in the Albertina, Vienna. The Vaduz portrait and Albertina drawing have both traditionally been thought to depict the artist’s daughter, Clara Serena, who died at the age of twelve in 1623. As Held observes (see Literature), such a repeated portrayal of apparently the same sitter does suggest a close personal contact between artist and model.

Held also, however, downgraded the painting from being a Rubens to being a Follower of. As for provenance, this is what’s listed by Sotheby’s:

Possibly Mme Camille Groult, Paris;

Possibly Sir Robert Henry Edward (Alabert?) Abdy, 5th Bart., Paris;

Mrs. Peter Cooper (Lucy Work) Hewitt, New York;

Her Estate sale, New York, American Art Association/Anderson Galleries, 6 April 1935, lot 613;

Frederick R. Bay, New York, by 1936 until at least 1939;

Charles Ulrick Bay, New York, by 1942;

His widow, Josephine Bay Paul, New York, 1955;

By whom given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1960 (Inv. no. 60.169).

In the condition report, Sotheby’s discussed some retouching, but concluded “the painting is presentable and there is no need for further work. offered in an elaborately carved and gilt wood frame.”

Is it really a Rubens? Was Held wrong? That would be a happy ending, except, of course, for the Met.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Sotheby’s

*I consult to a foundation that supports the Met