For some time now, many museums have been reinstalling their permanent collections in new ways, moving away from a chronological progression to more thematic placements. Supposedly, thematic hangings are easier for visitors to understand — at least that’s the usual explanation for them.

Now we have the Tate reversing course. Beginning today,

Now we have the Tate reversing course. Beginning today,

…visitors can experience the national collection of British art in a continuous chronological display – a walk through time from the 1500s to the present day. BP Walk through British Art will comprise around 500 artworks over a newly configured sequence of over 20 galleries. The displays include works by major artists such as Francis Bacon, John Constable, William Hogarth, Thomas Gainsborough, George Stubbs, J.M.W. Turner, Gwen John, Stanley Spencer, L.S. Lowry, John Everett Millais, Bridget Riley, Damien Hirst, David Hockney, and Rachel Whiteread.

Brother, do I hate that “BP Walk through…” credit line, but that’s another post. Oh yeah, and another.

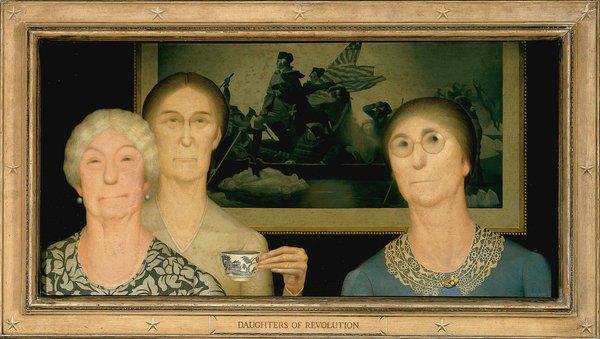

The Tate (I know it doesn’t use the article, but I do…) has also devoted new rooms to William Blake and Henry Moore, joining the Clore galleries that display the works of J.M.W. Turner, and now, Constable, too. It has also hung works by England’s first female professional painter, Mary Beale, including the portrait posted here, in an attempt to show more women artists.

But it’s the rehang that is of interest. Since 2000, the Tate Britain has mixed artists and periods in its galleries. The upside is this new approach (see this slide show), as the Tate, puts it:

But it’s the rehang that is of interest. Since 2000, the Tate Britain has mixed artists and periods in its galleries. The upside is this new approach (see this slide show), as the Tate, puts it:

The new chronological approach offers a fresh perspective highlighting surprising juxtapositions of art created within a few years of each other but rarely associated. An early Gainsborough landscape hangs side by side with Hogarth’s satires. The frolicking female nudes of Alma Tadema’s A Favourite Custom 1909, the epitome of Victorian revivalism, are seen next to Walter Sickert’s gritty modernist icon La Hollandaise 1906. Often separated when hung by movement or genre, the chronological presentation allows a more neutral view of the range of art being produced at any one historical moment to emerge.

Here’s more in the press release.

The Guardian rather approves. So does Richard Dorment in The Telegraph: “The permanent galleries have been rethought and re-modelled in a way that at last allows us to see the richness and variety of a national collection that in recent years has been lost to view….it is gloriously, satisfyingly, reactionary.” And the Times of London, though only subscribers can see past the first paragraph.

Might this signal a trend? I think I hope so.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of The Guardian (top); the Tate (bottom)