Several days ago, I asked here if any other art museums in the U.S. were spending as much money buying art as the Crystal Bridges Museum. I had added up the announced purchases over the past year or so by Crystal Bridges and it came to more than $150 million.

I could think of only the Broad, which hasn’t opened yet, as a contender. This morning, I received an email from the Broad announcing “more than 50 new artworks added to the Broad collection in anticipation of the September 20 opening.”

I could think of only the Broad, which hasn’t opened yet, as a contender. This morning, I received an email from the Broad announcing “more than 50 new artworks added to the Broad collection in anticipation of the September 20 opening.”

But I still think CB is spending more. That’s because:

Most of the additions to the 2,000-work Broad collection built by philanthropists Eli and Edythe Broad are artworks that were acquired within a year of the artist producing them, reflecting the museum’s commitment to build a dynamic collection of the most comprehensive and current contemporary art.

Interestingly, though, the names at the top of the release are all well-known. They include Julie Mehretu, Takashi Murakami (with “the largest painting in the Broad collectionâ€), John Baldessari, Ed Ruscha, Jeff Koons, Christopher Wool and Damien Hirst, a 1954 combine by Robert Rauschenberg and three sculptures by Cy Twombly. Less-known Goshka Macuga and Ella Kruglyanskaya were also cited.

Some of the new highlights:

- Mehretu’s Invisible Sun (algorithm 8, fable form), 2015, an ink-and-acrylic-on-canvas piece “currently on view at the Art Basel art fair in Switzerland.â€

- Robert Longo’s Untitled (Ferguson Police, August 13, 2014), a charcoal drawing of the Ferguson, Mo. police line last year, after the shooting death of Michael Brown; pictured above.

- Murakami’s 82-foot-long and 10-foot-high In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow.

- Macuga’s Death of Marxism, Women of all Lands Unite, Suit for Tichý 4 and Suit for Tichý 5.

- Kruglyanskaya’s Girl on a Hot Day, 2015.

- Hirst’s Fear, 2002 (thousands of dead flies thickly encrusted in resin)

- Wool’s Untitled, 2015, the 20th work by Wool added to the collection

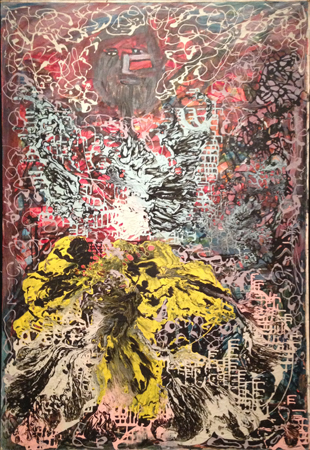

- John Currin’s Maenads, 2015

- Ruscha’s BLISS BUCKET, 2010; JET BABY, 2011; PERIODS, 2013; WALL ROCKET, 2013; and HISTORY KIDS, 2013 (five lithographs)

- Koons’s Hulk (Organ)

- Baldessari’s Pictures & Scripts: Honey – what words come to mind?, 2015; Horizontal Men, 1984; plus a full set of screenprints from his 2012 Eight Soups series (bringing the collection’s Baldessari holdings to 40 works spanning nearly 50 years).

- Twombly’s three sculptures brings the collection’s holdings in work by Twombly to 22.

More pictures are here.

Photo Credit: Petzel Gallery via The Guardian