Here’s another one of those you-can’t-make-this-up stories, which I received in a press release this morning:

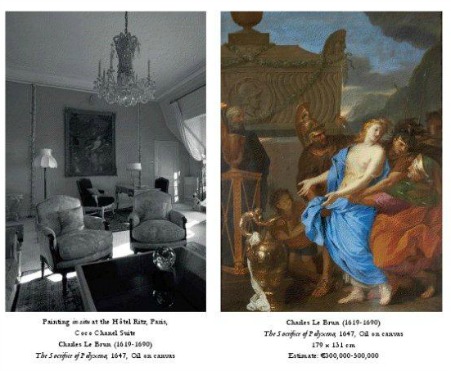

A previously unrecorded painting by Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), official painter to the ‘Sun King’ Louis XIV, has been discovered hanging in the Coco Chanel Suite at the Hôtel Ritz in Paris by the London-based fine art consultant Joseph Friedman. Formerly Curator of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor’s residence in Paris, Friedman was advising the hotel on its current €200 million renovation project when he came across the work. The painting, thought to depict The Sacrifice of Polyxena, will go on public view in New York at Christie’s from 26 to 29 January 2013 before being auctioned by Christie’s in Paris on 15 April 2013 (estimate €300,000-500,000).

The Ritz should be embarrassed, but it’s clearly not. Less than two  hours after I received that, Christie’s sent out its own release, noting “Occasionally, the biggest surprises are hiding in plain sight.” Then:

The Ritz should be embarrassed, but it’s clearly not. Less than two  hours after I received that, Christie’s sent out its own release, noting “Occasionally, the biggest surprises are hiding in plain sight.” Then:

…it was not found in a dusty attic, but on prominent display in the heart of Paris, in the most opulent and celebrated hotel in the world, the legendary Hôtel Ritz. The Ritz archives have not revealed how the painting came to the hotel or when it was first installed in the fabled ‘Coco Chanel Suite’, but it is possible that it was already in the townhouse (built 1705) when it was acquired by César Ritz in 1898.

The Sacrifice of Polyxena was painted soon after Le Brun returned to Paris from three years in Rome, where he studied the paintings of Raphael and came under the influence of Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665). This work clearly shows Poussin’s influence.

Sue Bond’s press release, the first quoted above, has more — she represents Friedman. At left is how the painting looked in the Chanel suite and what it really looks like.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Christie’s