It’s that time of year — actually, it’s a little past that time of year — when the Anonymous Was A Woman Foundation makes public the ten female artists who will receive $25,000 no strings attached, just to support them. This is the 19th set of winners  — and I was there at the creation, sort of. So I sometimes like to publicize the winners (which were announced on July 2).

The awards go to women over 40 “who have significantly contributed to their field, while continuing to grow and pursue their work.” This year they are:

The awards go to women over 40 “who have significantly contributed to their field, while continuing to grow and pursue their work.” This year they are:

- Janine Antoni

- Nicole Eisenman

- Harmony Hammond

- Kira Lynn Harris

- Lynn Hershman Leeson

- Hilja Keading

- Elizabeth King

- Beverly Semmes

- Elise Siegel

- Marianne Weems

These women paint, make sculpture and ceramics, work in theater and performance art. Five are from New York; the rest are from elsewhere in the U.S.

It’s too bad we still have to make special awards for women artists, but I don’t think the playing field is level yet.

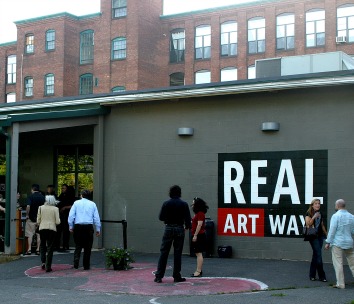

Photo Credit: production still from House/Divided by Marianne Weems, via the Anonymous Was a Woman FoundationÂ