Talk about a life: Alma Thomas was born in Georgia in the 1890s, one of the most vicious decades of the Jim Crow South. She told a reporter in 1972 that when she was young, blacks like her could not enter museums. Yet that year she became the first African-American woman to be honored with a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

But it wasn’t her biography that drew me, and that draws others nowadays, to Alma Thomas. It’s her exuberant art–something she took seriously only after she retired from teach art to middle-schoolers at the age of 69.

But it wasn’t her biography that drew me, and that draws others nowadays, to Alma Thomas. It’s her exuberant art–something she took seriously only after she retired from teach art to middle-schoolers at the age of 69.

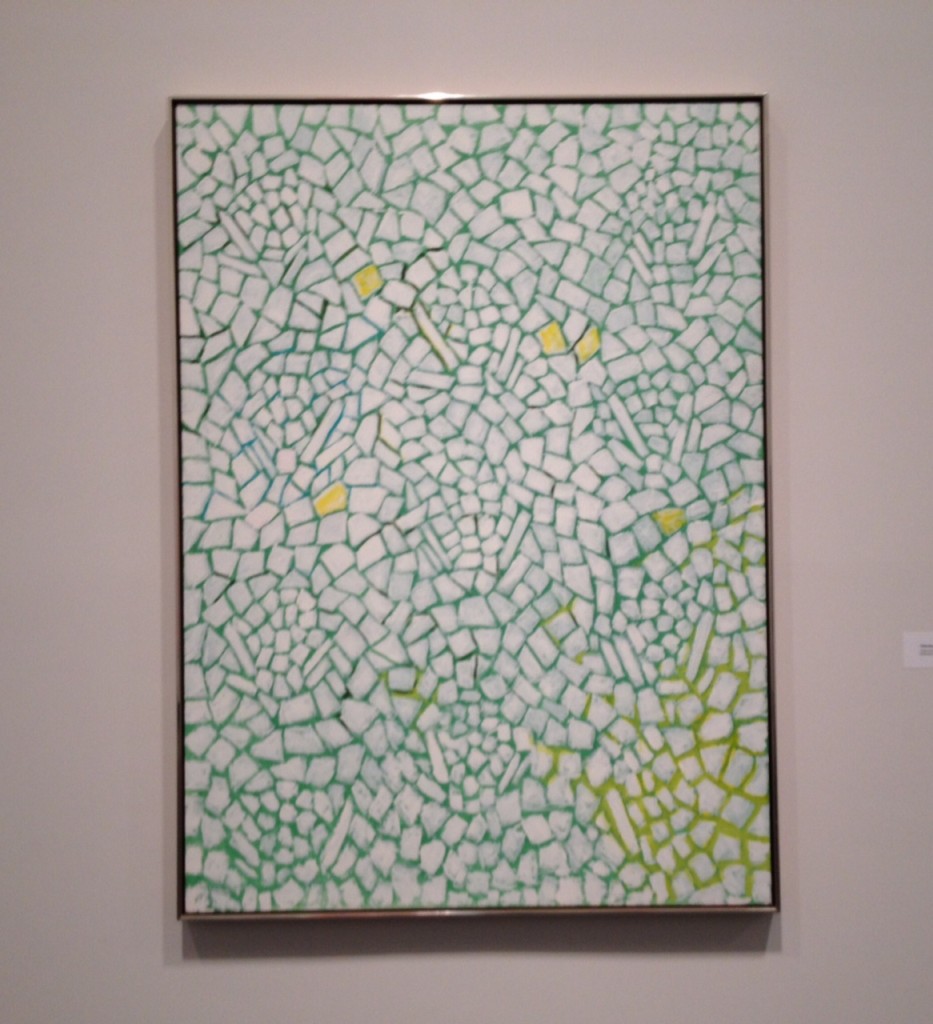

In fact, one of the most memorable works I noticed when the Whitney opened downtown last year was her “Mars Dust,” which had been purchased from the 1972 show but, in recent years at least, kept in storage. I had heard of Thomas, but I’m not sure I had ever seen her works in person until then.

So when a press release arrived saying that the Tang Teaching Museum at Skidmore was giving her a show, I quickly pitched a review to The Wall Street Journal,  which published it today. You can read it here (and see a different painting of hers).

Before she died, Thomas gave or bequeathed many works to the American Art Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, so take a look at those works.

I love many of her works–though not all–and another thing I love about her is her flair for titles–especially when so many artists cop out and slap “Untitled” on their work. Not Thomas. Her titles are as imaginatively engaging as her art. There’s “Snoopy See Earth Wrapped in Sunset,†“Breeze Rustling Through Fall Flowers,†“White Roses Sing and Sing,” “Scarlet Sage Dancing a Whirling Dervish” and many more like that.

What a charmer.

More good news: Â you can see the exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem this summer if you cannot make the trip to Saratoga Springs.

UPDATE: I have retrieved some installation shots from my phone to share:

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Whitney Museum (top) and me.