The Guggenheim Museum, despite suffering a power outage to its downtown administrative offices, which are closed (its email and phone systems are also down), managed to get out some news today (the museum itself was closed, as usual for Thursdays, but it plans to reopen tomorrow — it has been closed since Sunday, but opened yesterday only for Picasso: Black and White). So I thought it was worth a post: the museum named Danh Vo as winner of the Hugo Boss Prize. It’s the 9th time for the biennial prize, which involves a $100,000 award. The jury’s citation:

We have chosen to award the Hugo Boss Prize 2012 to Danh Vo in recognition of the vivid and influential impact he has made on the currents of contemporary art making. Vo’s assured and subtle work expresses a number of urgent concerns related to cultural identity, politics, and history, evoking these themes through shifting, poetic forms that traverse time and geography.Â

I can’t agree or disagree — the work leaves me befuddled — so I’ll post a few pictures and comments. Here’s one (Tombstone for Phùng Vo — at left) from the competition. The Walker Arts Center, which owns several works by Vo including that piece, has an interesting rationale for its choice by curator Bartholomew Ryan that begins:

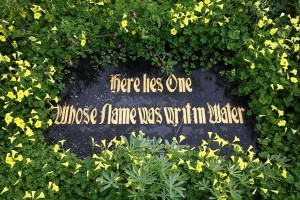

“Here lies one whose name was writ in water.†So reads the inscription on a black stone with gold-leaf engraving that will be installed in the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden in the spring of 2012. Titled Tombstone for Phùng Vo (2010), it’s one of several works by artist Danh Vo recently acquired by the Walker. …it’s my hope that this piece becomes a part of the life of the Twin Cities—that people will discover it and notice as the installation changes over time. In fact, the tombstone itself won’t always be here. On the death of the artist’s father, Phùng Vo, the stone will be shipped to Denmark and placed over his grave in Vestre KirkegÃ¥rd, a large cemetery in Copenhagen….

Just as immigration documents have controlled his family’s movements in life, the Walker’s acquisition of Vo’s work has led to contractual obligations that will impact various activities after his father’s death:…Phùng Vo has created a will for the Walker that …bequests to the institution four artifacts of personal significance, including a gold crucifix with a chain and three objects based on versions he purchased soon after he arrived in Denmark. These items—a Dupont lighter, an American military class ring, and a Rolex watch—have since been “upgraded†to newer models. Phùng Vo bought them originally because as a recent immigrant from Communist Vietnam, they symbolized a particularly Western brand of success and masculinity.

Whereas the tombstone will rest within the protective enclave of the Walker until it is sent to the cemetery in Copenhagen, these four objects will be part of Phùng Vo’s daily life until he dies. After the tombstone arrives in Copenhagen, the artifacts will be delivered to Minneapolis where they can be installed in a vitrine designed by the artist.

And here’s what Frieze magazine said about him in 2007, reviewing a show in Berlin:

Danh Vo investigates the invisible boundaries between the public and the private, and the possibility of their porousness. He undermines the institutional (he curated an exhibition of works by well-known artists in his parents’ house in Copenhagen) as well as the personal (he has married and then divorced several people, augmenting his name with theirs but not sharing a private romantic life). He has collaborated on a project with Tobias Rehberger without declaring his co-authorship, and stolen an idea from his artist boyfriend for his own funding application. Vo adopts appropriation more rigorously than is often the case, to discover how much a person can actually appropriate. Another person’s idea? An art work? An identity? There is a constant back and forth that questions authorial status, ownership and the role of personal relationships that prevents the ‘appropriator’ from keeping the upper hand….

See what I mean? Vo’s work is undoubtedly thought-provoking, but I haven’t seen it in person (at least I didn’t take note of it, if I have). Until then, I have to reserve judgment. Â

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Guggenheim (top); of Frieze (middle)