When Sotheby’s took to the press release in early September, announcing that it “won” the consignment to sell the estate of Alfred A. Taubman–the auctioneer’s one-time owner–it raised a lot of questions. While Christie’s competed for the consignment, Sotheby’s had to win–not doing so would have cost it a lot of face. But in the end, losing it may have proved to be the prudent thing to do–considering that Sotheby’s provided a universal guarantee of $500 million.

Even then, dealers and other experts I spoke with were skeptical; now that highlights have been shown in Hong Kong and London and that a vast amount (if not all, I’m not clear on that point) is on view in New York, I think the skeptics have a point.

Even then, dealers and other experts I spoke with were skeptical; now that highlights have been shown in Hong Kong and London and that a vast amount (if not all, I’m not clear on that point) is on view in New York, I think the skeptics have a point.

I went to look yesterday and saw little that convinced me the sales will reach $500 million. That means that Sotheby’s will be stuck with a lot of unsold art.

Of course there are some good pieces–to name a few:

- Modigliani’s Portrait de Paulette Jourdain, estimated at $25- to 30 million

- Degas’ Danseuses en blanc, estimated at $18 million to $25 million, plus two other Degas pastels (one good at $15- to $20 million, one less so)

- Two Rothkos, one small and colorful ($20- to $30 million); the other large and more somber ($20- to $30 million)

- Frank Stella’s Delaware Crossing, $8- to $12 million

- A couple Picassos, Giacomettis, a Matisse ($12- to $18 million)

- Heade’s The Great Florida Sunset, $7 to $10 million (above left)

- At least two dozen Schiele works on paper

- A so-so deKooning and Jasper Johns

- Several Burchfields and three (or four?) Homers, all perfectly fine but not great; a beautiful Milton Avery, but then others by him, too

And on and on: and that’s the trouble: can Sotheby’s get top-dollar for all the main lots? To my eyes (and others I chatted with), there are very few masterpieces, no matter what Sotheby’ says. Even so, can it then sell the bulk of the rest? There are many mediocre works and some things I’d categorize as worse than that.

I do not know the high-low estimates for the entire estate–Sotheby’s would only provide the $500 million figure–but I think knowing it will be revealing.

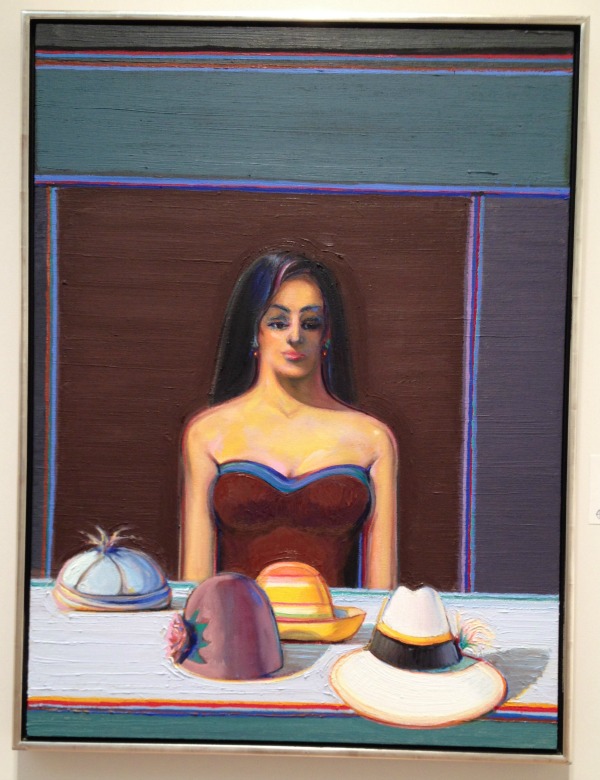

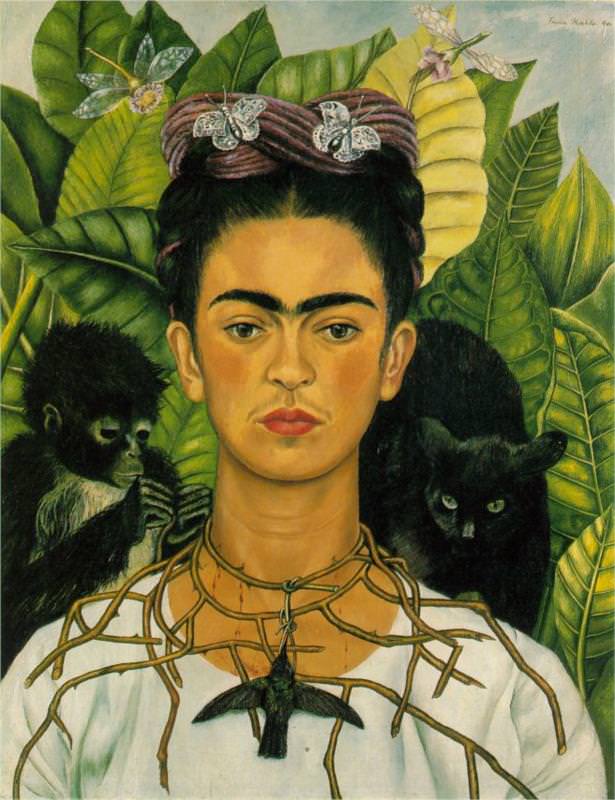

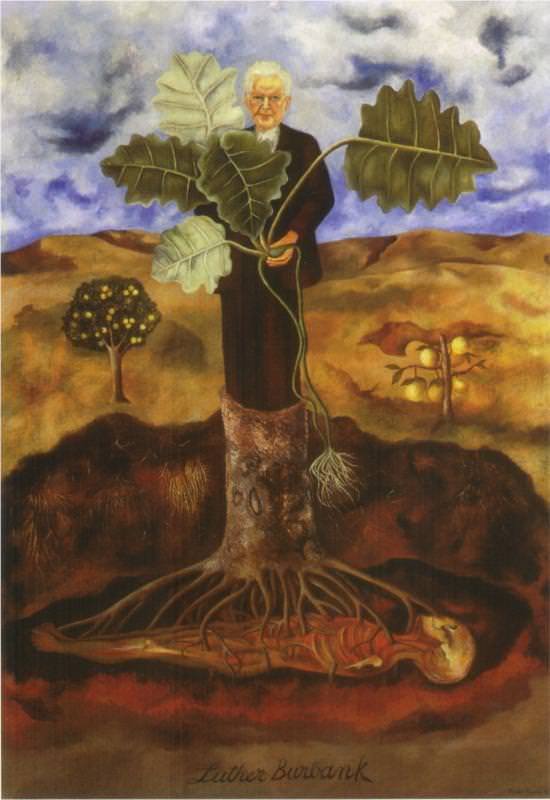

Meantime, I’ve posted some pix below from the exhibition, by (in descending order), Avery, Monet, Thiebaud, Vuillard, Carlsen and, finally, von Max.