To followup on my recent Cultural Conversation with John Patrick Shanley: “Doubt” premiered at the Minneapolis Opera on Saturday night and the reviews are starting to come in. I’m not surprised that they are mostly positive. For one, who’s going to criticize Shanley’s writing, even if it’s a new form for him? The reviews I’ve read barely mention the new elements he had promised, and delivered on, let alone comment on whether they work well.

To followup on my recent Cultural Conversation with John Patrick Shanley: “Doubt” premiered at the Minneapolis Opera on Saturday night and the reviews are starting to come in. I’m not surprised that they are mostly positive. For one, who’s going to criticize Shanley’s writing, even if it’s a new form for him? The reviews I’ve read barely mention the new elements he had promised, and delivered on, let alone comment on whether they work well.

Mostly, the critics comment on the music and the singing.

Here’s the Minneapolis StarTribune review,

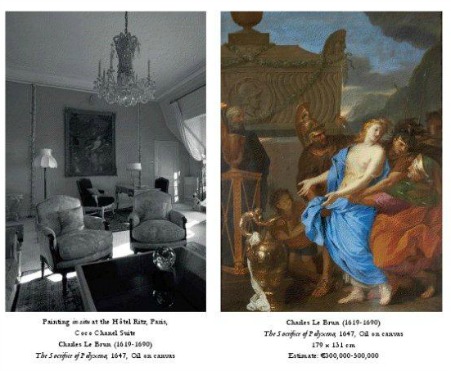

“…Cuomo’s music is of quiet power, most moving when most intimate; he knows how to insinuate what cannot be spoken. Though unmistakably American in sound, with echoes of Copland, Bernstein and John Adams, he avoids both pop cliché and music-theater razzmatazz. If Cuomo’s vocal lines sometimes seem awkward, his pacing is remarkably deft…Alive to Sister Aloysius’ steeliness, vulnerability and quirky humor, Christine Brewer [right, in the photo at left] makes her one of the most fully realized characters in contemporary opera. This is a great performance by a consummate singer; that it comes in the context of a new work makes it all the more extraordinary….”

Here’s the St. Paul Pioneer Press review, which says in part:

Here’s the St. Paul Pioneer Press review, which says in part:

“…Douglas Cuomo’s music serves to expand the emotional palette of Shanley’s words, layering levels of meaning onto exchanges and adding extra shadings to an already complex tale….It’s impressively sung and staged, its story’s ambiguity enhanced by Cuomo’s conflicted music. Yet the angular, often discomfiting character of that music might make it a tough listen for some….His melodies take many an unpredictable turn, single syllables sail in on a plethora of notes, and seemingly inconsequential phrases are repeated for evident emphasis, while others of relative importance are sung simultaneously and swept away in swells of sound…”

And here’s the AP review, published by Salon: “… The opera, with a libretto by Shanley and music by Douglas J. Cuomo, makes for a gripping 2 1/2 hours of theater. …The loudest applause deservedly went to Christine Brewer, the distinguished American soprano who may have found the role of a lifetime as Sister Aloysius…”

So the big winner seems to be Brewer. That’s Denyce Graves at right, playing the role of Mrs. Miller.

UPDATE, 1/30: The Wall Street Journal has weighed in; it, too, likes the singing and the “spare and clever set,” but doesn’t think the music rises to the libretto.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the StarTribune (top) and the Pioneer Press (bottom)Â