How funny, and inconsistent, the public is sometimes. When the Metropolitan Museum* raised its suggested price to $25 earlier this year, the outcry was tremendous. Ditto the Museum of Modern Art’s* admissions hike — mandatory — to $22.50.

But when Christie’s charges $30 per ticket to see 850 items once owned by Elizabeth Taylor — “including [her] legendary jewelry, haute couture, ready-to-wear fashion, handbags and accessories, and a selection of decorative arts, and film memorabilia being sold in the live auction” for four days, Dec. 13-16, no one says boo. No one complains that the tickets to the exhibition (Dec. 3 through 12) are available only online, are timed and offer no discounts to students or seniors. Oh yes, and add the $30 cost of a “printed gallery guide.” (The catalogues for the four-day sale cost $300.)

But when Christie’s charges $30 per ticket to see 850 items once owned by Elizabeth Taylor — “including [her] legendary jewelry, haute couture, ready-to-wear fashion, handbags and accessories, and a selection of decorative arts, and film memorabilia being sold in the live auction” for four days, Dec. 13-16, no one says boo. No one complains that the tickets to the exhibition (Dec. 3 through 12) are available only online, are timed and offer no discounts to students or seniors. Oh yes, and add the $30 cost of a “printed gallery guide.” (The catalogues for the four-day sale cost $300.)

Is there also irony in the fact that Christie’s suggests that visitors spend an hour and a half in the exhibit?

Here are the answers to other frequently asked questions.

People will pay and go. Taylor’s items have been on a three-month global tour that has included stops in Moscow, London, Los Angeles, Dubai, Geneva, Paris and Hong Kong. Some of those shows were free, but Christie’s also charged for admission to the exhibition in Los Angeles, where “tickets…sold out online within a matter of days, and Christie’s added extra, late night viewing hours to accommodate the many fans and collectors who came to see the exhibition,” according to its press release.

Christie’s, of course, has every right to charge what it wants. The market is bearing it. But it does make one wonder why people will pay for celebrity but not for the highest arts. What’s the message for museums?

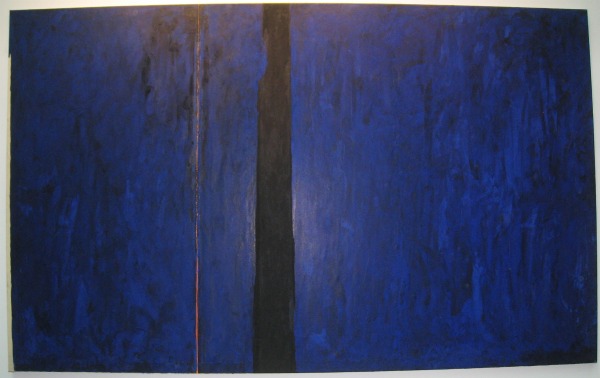

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Christie’s

*I consult to a foundation that supports the Met and MoMA.

This exhibition does, “focus[ing] on paintings and sculpture from three unofficial groups of artists, the No Names, the Stars, and the Grass Society, which pushed beyond Maoism in the early post-Cultural Revolution era. Each group pursued creatively diverse paths to artistic freedoms under the harsh political strictures and against the accepted aesthetic norms of the time. The work they produced opened the door for the avant-garde movement to emerge in China and paved the way for Chinese artists working today.”

This exhibition does, “focus[ing] on paintings and sculpture from three unofficial groups of artists, the No Names, the Stars, and the Grass Society, which pushed beyond Maoism in the early post-Cultural Revolution era. Each group pursued creatively diverse paths to artistic freedoms under the harsh political strictures and against the accepted aesthetic norms of the time. The work they produced opened the door for the avant-garde movement to emerge in China and paved the way for Chinese artists working today.”  I’m sure many people will visit at first. But it’s an open question whether Still’s art has the staying power, whether there’s enough interest in his works, enough variety in his works, to keep people coming. Last week’s auction,

I’m sure many people will visit at first. But it’s an open question whether Still’s art has the staying power, whether there’s enough interest in his works, enough variety in his works, to keep people coming. Last week’s auction,