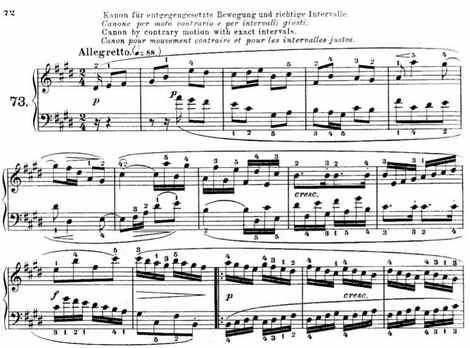

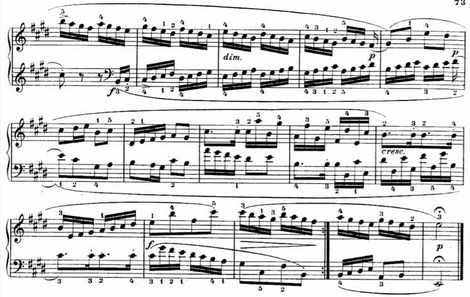

You can hear the canon here in a recording by Danièle Laval. Of course in E major he has to reflect the lower voice around F#, because the major scale (as a glance at the keyboard will show, noting D’s position among the white keys) is symmetrical around the second scale degree. Debussy tweaked fun at Gradus ad Parnassum in his Children’s Corner, and Charles Rosen blasts the collection as a marathon of mechanical soullessness. He’s almost 100 percent wrong. They’re all teaching pieces on some level, but included are dozens of lovely, memorable vignettes, variously diverging toward early Romantic harmony and warm neo-Baroque counterpoint.Â

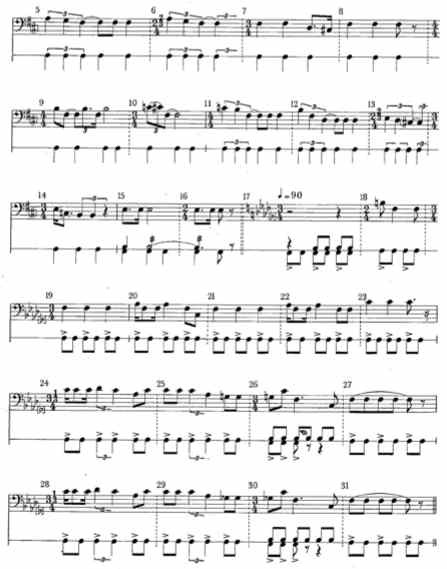

I’ve always gotten a kick out of keeping a secondary musicological specialty besides contemporary American music, sort of as a hobby and to keep new music in perspective. My period used to be medieval, which I studied in grad school with Theodore Karp, one of the leading figures in the field. But the last time I taught medieval, the textbook (by Jeremy Yudkin, the only enjoyably readable medieval music text) contradicted half of what I said, and I realized that that field changes too fast for me to keep track of – pieces are now attributed to different composers than was true when I was in grad school, and even the technical terminology has changed. So several years ago I switched to Classical Era as a secondary specialty, though I only do the instrumental music; most 18th-century opera bores me to tears. I enjoy taking students through the Haydn symphonies because they’re so incredibly varied and numerous, though it’s a rare student who shares my enthusiasm for Haydn. And I try to show them that the period was a lot funkier than it gets credit for, by playing Albrechtsberger’s concertos for jew’s harp, Michele Corrette’s Combat Naval with its forearm clusters on the harpsichord, and music in odd meters like this fugue in 5/8 by Beethoven’s childhood friend Antonin Reicha:

But I bring up Clementi’s inversion canon even in composition lessons as an example of grace achieved under intense compositional restrictions.