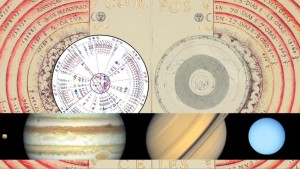

On October 12, the same day I will be in Belgium giving my keynote address at the Third International Conference on Minimalist Music at the University of Leuven, John Sanborn’s video to my piece The Planets (as recorded by the indomitable Relache ensemble) will premiere at the Mill Valley Film Festival at 6:45 at the Smith Rafael Film Center, San Rafael, CA. (Above, a still from “Uranus.”) A second showing will occur Friday, Oct. 14, at 8:45. The 11-day festival draws 40,000 audience members, and I’m very excited by the opportunity to get one of my major works past the circumscribed barriers of the new-music world and out to a larger, nonspecialist audience. John’s films are, I think, magnificent and erudite and sexy, and make the music fly by so fast that the whole thing seems like 20 minutes instead of 75. Below, stills from “Jupiter” and “Mercury,” respectively:

You can hear Venus and Uranus on my web site, and purchase the unfortunately rather difficult-to-find CD at the Meyer Media web site. (Maybe we should re-market it as “Soundtrack from the John Sanborn film The Planets“! I know it would sell more copies. Regular people actually buy soundtracks.)

Oct. 16 is the official release date of the 50th-anniversary edition of John Cage’s book Silence, with a new foreword by myself, so this is one of the biggest weeks of my life. [UPDATE, 10.3 – My copy just arrived in the mail.]

While I’m indulging in shameless self-promotion, new-music fan Ulysses Stone has created a playlist of postminimalist music on Spotify, based on my postminimalist discography (which is seriously in need of updating, if I can ever get around to it). Apparently, you need a Facebook page to get on, so I can’t, or won’t.