I would like to write something about my new piece Kierkegaard, Walking: not to draw attention to it, but because of a technical aspect of the work that I think draws together a number of late-20th-century influences and says something about the extent to which musical ideas can be style-independent. On a personal level, this is to fill in gaps in the lengthy drinking discussion John Luther Adams had the other night about our respective premieres, and also to clarify for anyone curious that my new piece does indeed intend to do what it seems to do. Consider this a kind of extended wonkish program note of the kind I would write if I assumed audiences had infinite patience and infinite interest in the details of the composer’s creative process.

Scene 1: Almost anyone who would be reading me knows what happens in the startling ending of Morton Feldman’s Rothko Chapel: it is one of the most famous effects in recent music. For some 15 minutes we’ve been immersed in a splintered sound world whose disconnected images at least seem homogenous in style and origin. Dissonant chords float by with the pulselessness of clouds; beatless soprano and viola melodies emerge from the distance, and occasionally a hesitant timpani pulse pushes against the grain of the meter. No one at the premiere (or listening to the recording when it was new) would have failed to understand this as a continuation of the soundworld of the 1950s avant-garde.

But suddenly – you know what happens – a vibraphone picks up with a cheerily repeating G B A C motive that sounds like it belongs to a different piece, a different composer, a different era. (In his Seattle talk, Alex Ross connected it to a motive from Stravinsky’s appropriately neoclassic Symphony of Psalms, and noted that Feldman was working on the piece the day of Stravinsky’s funeral.) One might as well have Winnie-the-Pooh and Piglet skipping onstage in the fifth act of Macbeth. The dark poignancy of the first 15 minutes of the piece is unveiled as artifice, as fiction. The contingency of an ostensibly “natural” style is frankly admitted, one’s suspension of disbelief dispelled. It’s a magnificent sucker punch, one of the great postmodern gestures.

This is not the only place in which Feldman ends a piece by opening a door that leads the listener out of his soundworld and back into the real one. In Why Patterns? the three instruments play for half an hour in mutually oblivious time worlds, parallel lives. Then at the end, after each has exhausted its material, they quietly fall into regular 3/8 meter and descending chromatic scales. Following the predictable weirdness of Feldman’s universe comes a passage so obvious, so banally normal, that no other composer would have ever dared pen it.

Scene 2 of our story takes place in the same decade, but musically in a very different location. George Rochberg, in the 1960s, had started writing pieces that juxtaposed fragments of incommensurate styles: bits of Mozart, Mahler, Webern, Miles Davis butting up against each other like someone twirling the radio dial. (One might note a brushing similarity with Cage’s Variations IV.) A couple of years after Feldman wrote Rothko Chapel, Rochberg embarked on a series of string quartets for the Concord Quartet which went beyond quotation of famous works to writing in historical styles. Beethovenesque fugues lurch into Bartokian atonality, giving way to Mahleresque pathos or the Baroque French overture idiom. Though it was initially met by a flurry of some of the harshest professional outrage ever elicited by mere music, Rochberg’s gesture emboldened others to strike out in this direction as well, notably William Bolcom and John Corigliano. Bolcom’s Fifth Symphony has the time of its life counterpointing the hymn “Abide with Me” and Lohengrin in a Mahleresque funereal style, then breaking into Tristan‘s Love-Death Music reinterpreted as a fox-trot.

For musicians, this was postmodernism, as far as we understood it on our terms: the fracturing of the organic stylistic unity that one had always considered an inviolable premise of any work of art.

Scene 3: For my late and lamented colleague Jonathan Kramer, the problem with the Bolcom/Rochberg type of postmodernism was that it almost necessarily degenerated into potentially satiric collage, a kind of high-class P.D.Q. Bach. Jonathan was obsessed with this aspect of postmodernism. He didn’t live to quite complete his book Postmodern Music, Postmodern Listening, but I’ve read the manuscript, and people are working on it; when it finally appears, the book will revolutionize the way musical postmodernism is understood. For Jonathan (though this is not strictly to our point), postmodernism is not so much a quality of musical works as a kind of listening potential which some pieces of music encourage more explicitly than others.

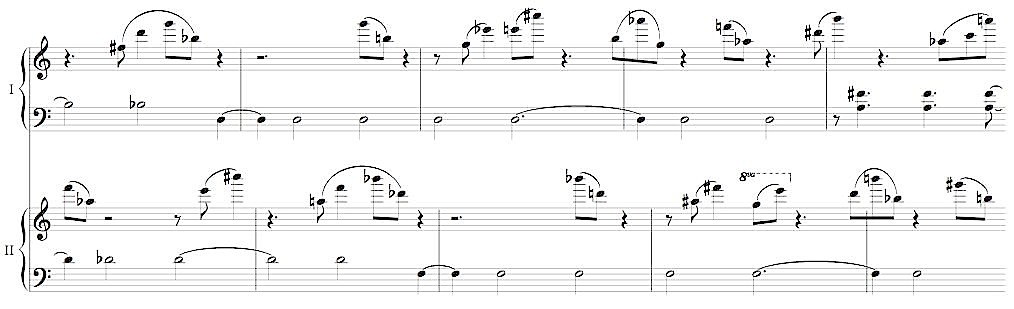

After Jonathan’s early postminimalist phase, he began pursuing the postmodernist idea creatively. In 1992-3 he wrote a superb piece called Notta Sonata which constituted a critique of Bolcom and Rochberg just as surely as Kierkegaard’s Philosophical Fragments constitutes a critique of Hegel. Notta Sonata is for two pianos and percussion, intended as a companion piece to the Bartok Sonata and just as exciting in performance. It’s a shame the piece isn’t yet available on recording, but you have to hear it if I’m going to talk about it, so I post its two humorously titled movements here:

Notta First Movement (11:28)

Also Not a First Movement (12:09)

(The piece starts very soft and soon gets very loud. I’ve compressed the dynamics a little for fear computer listening would be totally inadequate.) For Jonathan, the more interesting musical option was not to use other composers’ styles in your music, but to make up imaginary styles that had never existed. Thus Notta Sonata contains (to quote what I once wrote about it)

passages [that] sound like Baroque counterpoint on mallet instruments, tonalized fragments of Boulezian serialism, piano horn calls from a Weber opera reworked by Stockhausen with raucously ringing glockenspiels.

Notta Sonata represents a fractured consciousness, an advanced case of stylistic schizophrenia, without sounding like a trip through some composition teacher’s record collection. Adding to the rioutous effect is that the music often breaks off abruptly, veers off in a raucous new direction, and then snaps back serenely to where it left off, as though one stretch of tape were spliced into the middle of another. So many passages in it conflate styles that don’t fit together, with qualities that no other composer ever thought to fuse in one measure. As far as I know his output, it’s Jonathan’s masterpiece: a very important (and thoroughly entertaining) work whose historic position and theoretical achievement will inevitably be recognized someday. Why not right away? What are we waiting for? It’s been around for 15 years.

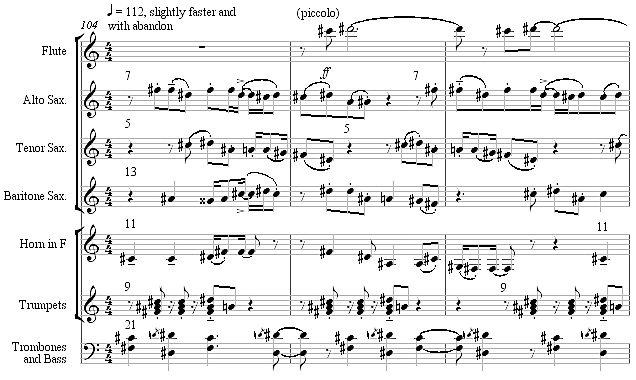

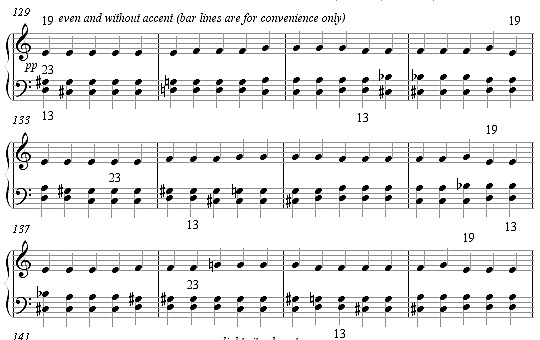

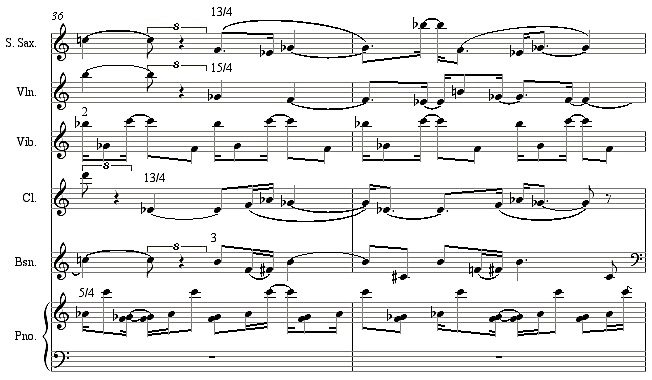

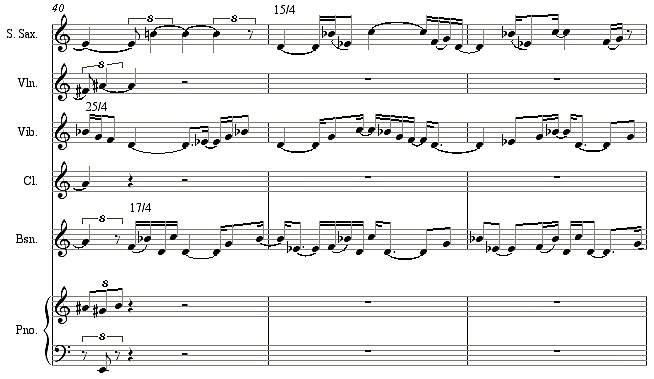

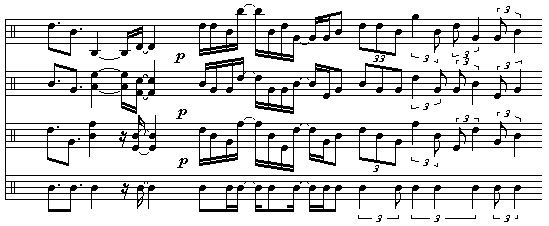

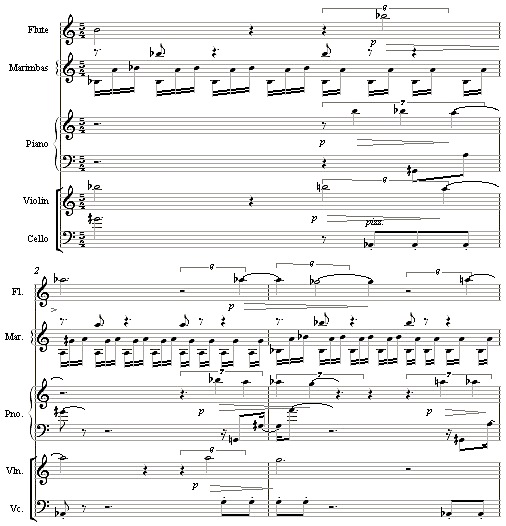

Scene 4: This brings us to my own quieter and more modest effort Kierkegaard, Walking. The piece transfers the collage effect of Notta Sonata to the quieter level of Feldmanesque negation; or to put it another way, it pursues Feldmanesque discontinuity on the more pervasive level of Notta Sonata‘s collage technique. The fragments fused together in the piece are not expansive or complete enough to be distinguished as styles: each is little more than a group of out-of-synch repeating phrases with a certain rhythmic character, based around a harmony or tonality:

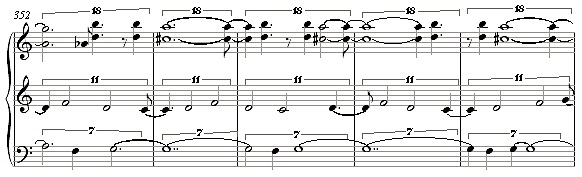

The tiles of the mosaic are carefully and intuitively balanced and contrasted as to direction and function: tonal against atonal against polytonal, rhythmically regular against syncopated, additively processed against repeating against through-composed. You could think of each one as a Feldmanesque mini-texture, say, the repetitions of Crippled Symmetry regularized into quarter-notes and 8th-notes. You can listen to a good rehearsal tape of the piece here (15:12), or download a PDF score here.

At the same time, the radical distancing gesture of Feldman’s closing disjunctions is normalized into a series of smooth nonsequiturs, like the mountains of Notta Sonata squeezed into a narrow corridor. No passage bears a direct link to its immediate predecessor or successor, but a center, or perhaps multiple centers, can be intuited of which the different passages are manifestations. The most recurrent idea, a series of loops going out of phase with each other, comes back almost as a series of variations on a texture. That image contains within itself a friction between time and timelessness (another Kramer obsession, which he pursued in his fantastic book The Time of Music), since the repetitiveness denies forward progression while the changing combinations imply forward movement. The connection with Kierkegaard is a parallel to the contrast of Either/Or, the time-related aesthetic life versus the sub specie aeternitatis meditations of religiosity; and also the fluid succession of fictional personas that Kierkegaard maintains throughout his written ouput. Taken as a whole, Kierkegaard’s total ouevre would be a model of postmodernism, speaking as Victor Emerita one moment, Johannes Climacus at another, and occasionally as Kierkegaard himself.

In being a series of nonsequiturs that relate to each other centrifugally rather than linearly, Kierkegaard, Walking has other, related sources. The centrifugal form – a nonlinear succession of phrases that point to a central idea – calls to mind Nancarrow’s Study No. 24, which I’ve always thought of as his most elegant and most perfectly crafted work. That piece has no motives or harmonic materials of more than local significance, yet derives a powerful unity from the derivations of its alternating A and B sections from a pair of textural ideas, manifesting differently depending on where they occur in the accelerating tempo structure. Another, more obvious model is Erik Satie’s exquisite Socrate, also a series of quiet nonsequiturs, seemingly without center.

Of course I don’t mean to imply that this is how I consciously arrived at the piece: few of my works have seemed to flow from my subconscious so smoothly, without me “knowing WTF I was doing.” But these pieces are all models deeply implanted in me, and which, in retrospect, I recognize as having prepared me for Kierkgaard, Walking. I was very much into the collage idea as a teenager, actually; an ensemble piece of mine from high school (not worth reviving) pits a marching-band version of The Rite of Spring against Liebestraum. But then minimalism came along, and narrow focus was the order of the day. It was when I started writing for Disklavier that collage techniques began to interest me again, because it was so easy to crash fragments into each other without worrying about performance logistics.

In any case, the stylistic nonsequitur has become an option of our current compositional arsenal, and it is clear that it can serve as many different purposes, perhaps, as there are composers to use it:

* the Zen confidence of Socrate

* stylized depiction of rural life (Virgil Thomson)

* bracketing of an otherwise homogenous style (Feldman)

* commentary on the history of music (Bolcom)

* schizophrenia, or perhaps more normal disjunctions in consciousness (Kramer)

* imitation of channel-surfing and other technological intercutting (John Zorn)

* mimicking a Kierkegaardian conversation with its points of stability and abrupt transitions of persona (Kierkegaard, Walking)

There will never be another Rothko Chapel, and that effect can never be achieved the same way again. But no composer today need any longer assume, as he’s working on a piece, that the next measure need remain in the same style, or inhabit the same world, as the one he’s working on at the moment. It’s a curious thing to think about.