I’ll bet that if you ran a new-music series and gave composers the following choice – “We’ll either give you a $500 honorarium, or you can have $100 and talk about yourself to the audience for 20 minutes” – almost all composers who aren’t in dire financial straits would choose the latter option. When the subject is ourselves, we do not like to shut up. I was on a panel of composers last night preceding the Cutting Edge series concert at Symphony Space, and the desire to chatter on was palpable. William Bolcom was the grand old man of the group, and seemed accustomed to occupying a stage by himself; we all deferred to him and let him talk most. Two of the other composers had, in fact, been students of his. Composer Victoria Bond, who runs the series, has clearly been in the moderation business a long time. She cut off each composer as graciously as though he had come to the end of a prepared text.

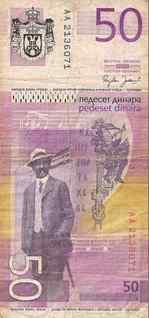

Whence comes this intense desire for self-expression? The yearning to have our music played, the prestige of gigs, the need to get money for our work, are all easily understandable. But why do I want the audience to know, before it hears my music, that I studied with Ben Johnston? Victoria drew a tentative connection between a vernacular element in my work and the fact that I’m from Dallas, and I slightly bridled at being thought of as a “Dallas composer.” Why? How silly. Do we imagine we’ll be the more admired if we say something clever? that some credential we bring up offhandedly will convince someone to give our music a more serious listen? Why does the picture our music draws seem so incomplete? The desire isn’t quite universal. Conlon Nancarrow was famous for answering series’ of long questions with a bare yes or no. Frederic Rzewski seems to use the interview format to prevent people from learning anything about him. But most of us are pathetically eager for an opportunity to represent ourselves, to draw a picture of our character for the audience. And, being so, we naturally bend over backward not to appear so. Every composer learns to efface himself in such situations, to substitute for some unyielding conviction a gentle joke that signals that he doesn’t take himself too seriously. We take turns out-modesting each other. We sensitize ourselves to the slightest clue that the interviewer is ready to move on. We conform, chameleonlike, to whatever level of discourse our peers launch into.

I’m old enough to recall when composers spoke more dogmatically and aggressively in public. Back in the day when we tended more to be judged by the intricacy and objectivity of our systems, we were more given to explanation. Composers informed the audience what to listen for, detailed their patented pitch methods, proclaimed their allegiances to this school or that. Of course we all know why this went out of favor. The audience didn’t much care about those pitch systems anyway, and rarely heard what we told them to hear. We were shamed out of that dogmatic technical mode, and scarred by the aesthetic battles that were its context. Next, starting in the late 1980s, came the “influences” trope: “My influences include….” For the liberal among us, “my influences” generally included Arnold Schoenberg and John Lee Hooker, or Brian Ferneyhough and the Sex Pistols – to prove to the audience that though we were intellectuals, we weren’t snobs.

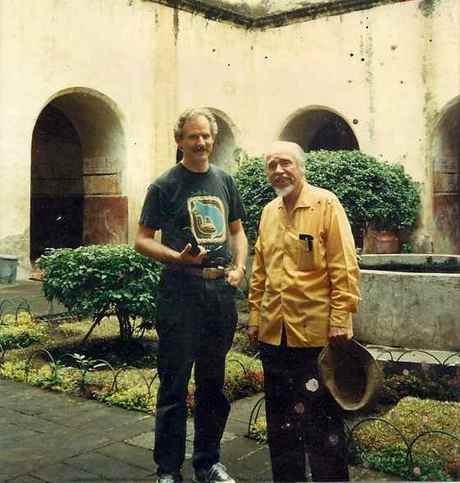

These days it’s all personal. Paul Yeon Lee heard his piece in a dream. Derek Bermel got his compositional idea from listening to foreign-language tapes. William Bolcom talked about underrated musicians he had known. Mark Grey extolled the colors of the light in the valley in Austria where he lives. I talked about visiting Nancarrow in Mexico City. After the bad old days in which composers used to impress their audiences with technical expertise and quasi-scientific musical mandates, we seem to be on a huge swingback, more modestly just trying to convince the audience that we’re nice, down-to-earth guys. (I don’t mean to single out this concert at all: I’ve been noticing this phenomenon for more than a decade, and used to write about it at briefer length in the Village Voice.) The prestige of the modern composer has fallen so far that I think the reflexive self-effacement is a true reflection of the perception that society doesn’t take composers very seriously anymore. Still recoiling from the days in which we were all trying to be the next Stockhausen, now we’re all trying to convince the audience members that we’re just like them, except we write music. In front of an audience of complete amateurs this has one effect, but seems a little different in front of the musically sophisticated listeners that the Cutting Edge Concerts seem to attract, or so it felt. Despite the thousands of hours we put into honing our compositional philosophies, we’re afraid to be leaders, or to pretend to be experts.

But we composers have more to say than this. What did it mean that Bolcom’s trio had clear, vernacular-tinged rhythms couched in a bracingly dissonant pitch language? Or that Grey’s A Rax Dawn for piano was precisely the opposite, lushly Romantic in its harmonies but fluidly mercurial and complex in its rhythms? What do such choices have to do with our strategies for reaching an audience? In 2009, each of us can choose any musical language he fancies; what philosophic or social concerns guide our choices? How are composers responding to the world financial crisis? The response in 1933 couldn’t have been starker: abstract, dissonant music was abruptly discredited, writing music for the masses was in, and quoting Appalachian folksongs got you extra credit. What’s our response now? Some of us pitch our music toward audiences, quoting or appropriating whatever elements might draw them in. Others devoutly believe in autonomous personal expression, and are content with however small an audience their idiosyncrasies attract. How are we dealing with the ascendence and hegemony of commercially supported pop music?Â

No one wants the aesthetic battles of the 1980s to return, but by now we ought to be able to address big issues without dogmatism. I, personally, regret the lack of substantive dialogue in the current new-music scene, but it seems symptomatic of our current condition. Privately, I imagine we are all still inspired by Big Ideas – I know I am – but publicly, we hide their effect. Perhaps we’re in too mushy a period to draw coherent distinctions. We’re split into subcultures, and no one wants to offend anyone else. Everyone feels a little helpless. No generalizable new language beckons. The personal seems safe, unthreatening. But where are the important issues facing early 21st-century music to be delineated? Certainly not by critics, who don’t understand the compositional issues at stake. Some of us composers are desperately trying to reach the audiences who fled from late modernism, but reluctant to admit that fact. Others continue in a straight line determined by their education, and don’t want to confront the popularity issue at all. I envy the discourse of novelists reviewing other novelists in the Times Book Review and the New York Review of Books: writing words about someone else’s words, they take on big issues, and are not reduced to personalities. I’ve spent thousands of hours contemplating what kind of music I ought to be writing, and I wish I could get out in public with other composers and work out the why and wherefore, rather than retreat into whatever personal tidbits of my life seem relevant to the piece at hand.

I came home and dreamed that I was ineffectively singing the Grandpa role in a school production of Copland’s The Tender Land (of which I bought a vocal score last week). The second act was taken up by a long monologue by the heroine Laurie’s rebellious little brother, whom I’d never noticed in the opera before – because he doesn’t exist. I’m still trying to figure that one out.