I’ve been posting way too many photos – probably more of you have already seen Yurp than I imagine – but I couldn’t resist this image of John Luther Adams (front) listening to his Veils and Vesper installation at the Muziekgebouw:

It was a fantastic space for it, high-ceilinged and well insulated from other spaces despite its openness, and surrounded on various sides by wood, concrete, metal, and glass – tieing in conceptually, in that respect, to John’s percussion music, which groups instruments via those categories. Walking among the different loudspeakers, you got a strong sense of each veil giving way to the next, like wandering through a series of waterfalls. I wish I could post a soundfile for you, but the music occupies ten full octaves, and contains lots of subtle acoustical stuff – like Phill Niblock’s and Eliane Radigue’s music, it would never survive MP3-ization.

In response to my last post, John offers:

Last year I revisited Emerson’s expansive essay “Nature”. As always, I was amazed at the breadth and depth of Emerson’s mind. And I realized how much I’d missed in my earlier readings. Soon after, I rediscovered Thoreau’s final essay “Walking”. Reading it took my breath away, like listening to the music of the hermit thrush. It felt to me like coming home.

As you say, Emerson and Thoreau couldn’t be closer in spirit. Yet their sensibilities couldn’t be more different….

In my own music, the human presence isn’t represented in the music itself. It’s there in the presence of the solitary listener immersed within the music.

After years composing music inspired by landscape, my recent works – particularly the installations – have literally become places. Now, I’m beginning to invite the human presence of performing musicians to traverse those lonely landscapes. Still, creating place in sound, time and space remains the heart of my work. I feel this is the best gift I can offer to my fellow human animals.

As our species begins to stare our own possible self-induced extinction squarely in the face, I believe that music can serve as a sounding model for human consciousness. Music can help us remember how to listen, and how to know our place within the larger world we inhabit.

All very true. As for me… well, at least I drive a Prius.

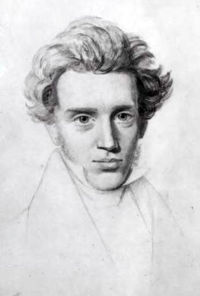

How the theologically provocative author of Fear and Trembling became one of those writers is difficult to say. I was reading Sartre in college, without understanding him much, because existentialism seemed like the cool philosophical trend of the time. Camus had a more concrete impact. I remember thinking that The Myth of Sisyphus did more than even ale could to “justify God’s ways to man.” But working backward through existentialist chronology, I ran into Heidegger, Husserl, Nietzsche, and finally Kierkegaard, and while I would later explore the others, it was only this last who grabbed deeply into my imagination. Perhaps I was attracted by the glancing resemblance of his last name to my full name, or the coincidence that he died almost exactly a century before I was born. More likely his position as the first phenomenologist of anxiety, fear, and depression offered a promise of kinship to my adolescent introversion. Whatever the underlying psychology, I spent, at Oberlin, a depressive, reclusive year reading almost half of the 43 books Kierkegaard wrote in his feverish 17 years of authorial activity, ignoring all else. The next year, once that fetish had played out, I sank even further into the abyss and read nothing but Samuel Beckett, who at least had the advantage of being considerably more concise. The less said about that spiritual crisis, the better. Suffice it to say that Godot did not arrive.

How the theologically provocative author of Fear and Trembling became one of those writers is difficult to say. I was reading Sartre in college, without understanding him much, because existentialism seemed like the cool philosophical trend of the time. Camus had a more concrete impact. I remember thinking that The Myth of Sisyphus did more than even ale could to “justify God’s ways to man.” But working backward through existentialist chronology, I ran into Heidegger, Husserl, Nietzsche, and finally Kierkegaard, and while I would later explore the others, it was only this last who grabbed deeply into my imagination. Perhaps I was attracted by the glancing resemblance of his last name to my full name, or the coincidence that he died almost exactly a century before I was born. More likely his position as the first phenomenologist of anxiety, fear, and depression offered a promise of kinship to my adolescent introversion. Whatever the underlying psychology, I spent, at Oberlin, a depressive, reclusive year reading almost half of the 43 books Kierkegaard wrote in his feverish 17 years of authorial activity, ignoring all else. The next year, once that fetish had played out, I sank even further into the abyss and read nothing but Samuel Beckett, who at least had the advantage of being considerably more concise. The less said about that spiritual crisis, the better. Suffice it to say that Godot did not arrive. All this prologue is to set up how excited I was to receive in the mail this weekend the Innova recording of the Concord Sonata – orchestrated by Henry Brant. In addition to being the leading composer for spatially separated ensembles, Brant has always had a reputation (furthered by Virgil Thomson’s writings from way back) as one of the greatest orchestrators ever. I heard his orchestration of the Concord, quite aptly retitled A Concord Symphony, at its New York premiere back in 1996, and was blown away then. This live recording by Dennis Russell Davies and Holland’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra makes it even more exquisite.

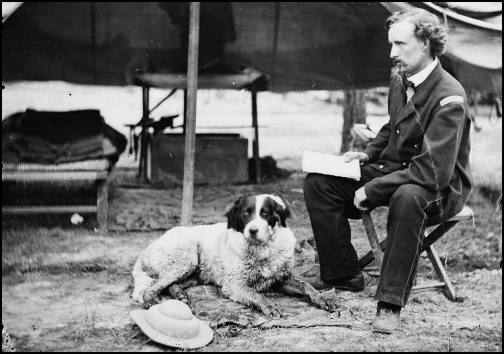

All this prologue is to set up how excited I was to receive in the mail this weekend the Innova recording of the Concord Sonata – orchestrated by Henry Brant. In addition to being the leading composer for spatially separated ensembles, Brant has always had a reputation (furthered by Virgil Thomson’s writings from way back) as one of the greatest orchestrators ever. I heard his orchestration of the Concord, quite aptly retitled A Concord Symphony, at its New York premiere back in 1996, and was blown away then. This live recording by Dennis Russell Davies and Holland’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra makes it even more exquisite. And so Mike Maguire and I have completely remade my one-man music theater piece Custer and Sitting Bull. Mike (whose composing name is M.C. Maguire) is not only one of the most surprising and innovative composers around, but an expert commercial sound engineer with broad experience in commercials and film. So I gave him the MIDI files and some general pointers, and he’s completely refitted the piece with new sounds, from the ground up – we got together in Toronto to go over the results with a fine-tooth comb. Mike’s sounds are indeed grittier, livelier, more energetic than the ones Dale Hourlland and I had once coaxed out of 1999 technology, but – what’s most important to me – they feel as supple and definite to perform with. I hope this stills some of the complaints I get about my electronic timbres, and if not, that’s the end of the line – my music is not for everyone. It’s my observation that some people are so attuned by pop music that they can listen only to production, to the extent that distinctions of syntax escape them if unorthodox production values get in the way. And then, to people reluctant to bend their ears to it, microtonal music will always sound simply out-of-tune, and the strangeness gets projected onto other elements as well.

And so Mike Maguire and I have completely remade my one-man music theater piece Custer and Sitting Bull. Mike (whose composing name is M.C. Maguire) is not only one of the most surprising and innovative composers around, but an expert commercial sound engineer with broad experience in commercials and film. So I gave him the MIDI files and some general pointers, and he’s completely refitted the piece with new sounds, from the ground up – we got together in Toronto to go over the results with a fine-tooth comb. Mike’s sounds are indeed grittier, livelier, more energetic than the ones Dale Hourlland and I had once coaxed out of 1999 technology, but – what’s most important to me – they feel as supple and definite to perform with. I hope this stills some of the complaints I get about my electronic timbres, and if not, that’s the end of the line – my music is not for everyone. It’s my observation that some people are so attuned by pop music that they can listen only to production, to the extent that distinctions of syntax escape them if unorthodox production values get in the way. And then, to people reluctant to bend their ears to it, microtonal music will always sound simply out-of-tune, and the strangeness gets projected onto other elements as well. But you knew I’d come back from a minimalism conference with some new obscuuuuuuuure recordings for

But you knew I’d come back from a minimalism conference with some new obscuuuuuuuure recordings for  And on the subject of Serbian postminimalism, which I’m sure you’ve brought up at a cocktail party by now, I’m happy to present several pieces by my new friend

And on the subject of Serbian postminimalism, which I’m sure you’ve brought up at a cocktail party by now, I’m happy to present several pieces by my new friend