Here, courtesy of OM-Radio director Richard Friedman, were the composers at Other Minds this year: Louis Andriessen, I Wayan Balawan, Han Bennink, myself, Janice Giteck, David A. Jaffe, Jason Moran, Agata Zubel, and Other Minds director (and fantastic composer himself) Charles Amirkhanian:

Here I am giving a presentation on my music and suddenly realizing that I had subconsciously plagiarized the theme from “Baywatch”:

Here the Djerassi landscape takes a long look at me and notable Dutch jazz drummer Han Bennink:

Here I am breakfasting with one of my best friends in the world Janice Giteck, trying desperately to remember why I never stand in front of a light source:

Here Louis Andriessen, Agata Zubel, Janice, and Charles discuss contemporary music as I seriously contemplate finding another line of work:

And here’s the barn in which we met every day:

Thanks to Richard for all the great photos. They’re not coming out well-focussed here – I have no idea why, they look perfect on my computer. (UPDATE: Richard says to click on them and they open in-focus.)

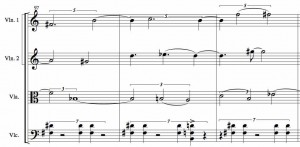

Trimpin, whose mischievously adolescent sense of humor is one of his most endearing qualities, had the best joke of the week. David A. Jaffe had inherited a bunch of percussion from his teacher Henry Brant, and he used those instruments in his piece The Space Between Us. Included were about 25 chimes, and Trimpin had the idea of suspending the chimes from the ceiling and having them played via MIDI. So David’s piece had two string quartets, one on each side of the audience, plus a Disklavier onstage, a couple of MIDI-played xylophones, and the chimes hung from the ceiling. On the preceding panel, as the audience sat underneath those chimes, David explained that Trimpin had suggested suspending the chimes, but that he, David, was afraid that they would fall down and strike audience members. Charles asked, “So Trimpin, how are the chimes suspended from the ceiling?”, and Trimpin answered, “Oh, with very thin twine….” The Space Between Us was perhaps the festival highlight, with the string quartets playing ethereal melodies with the disembodied chimes in rhythmic unison. It was a fantastic week. I’ve found so many composer gigs disappointing that my expectations are permanently set at zero, but this was a crescendoing pleasure.