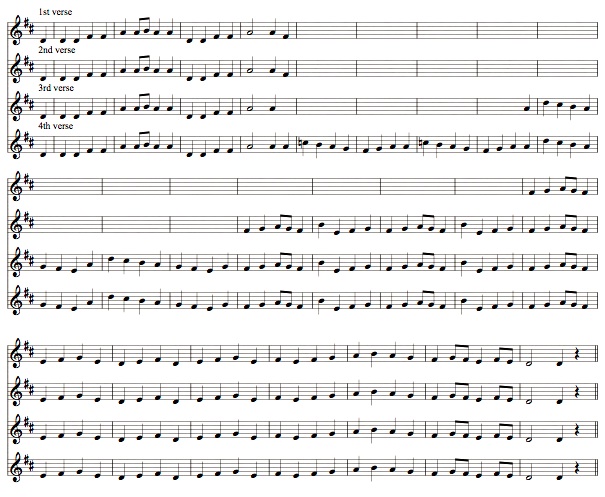

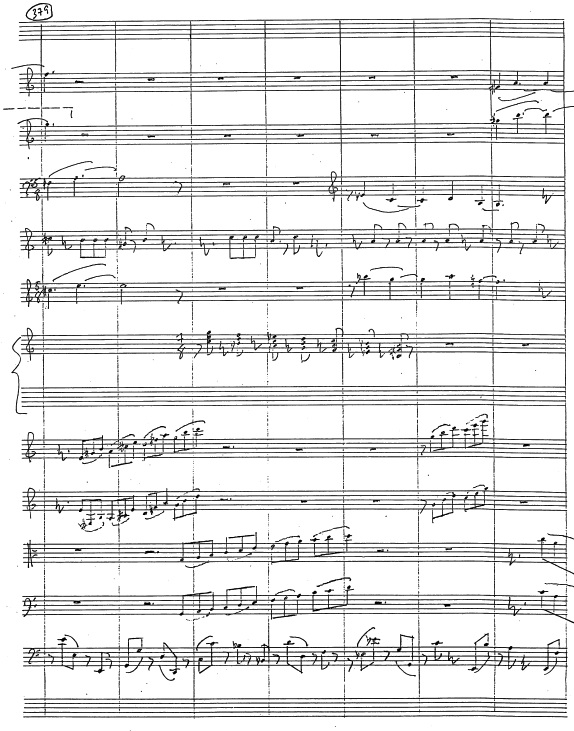

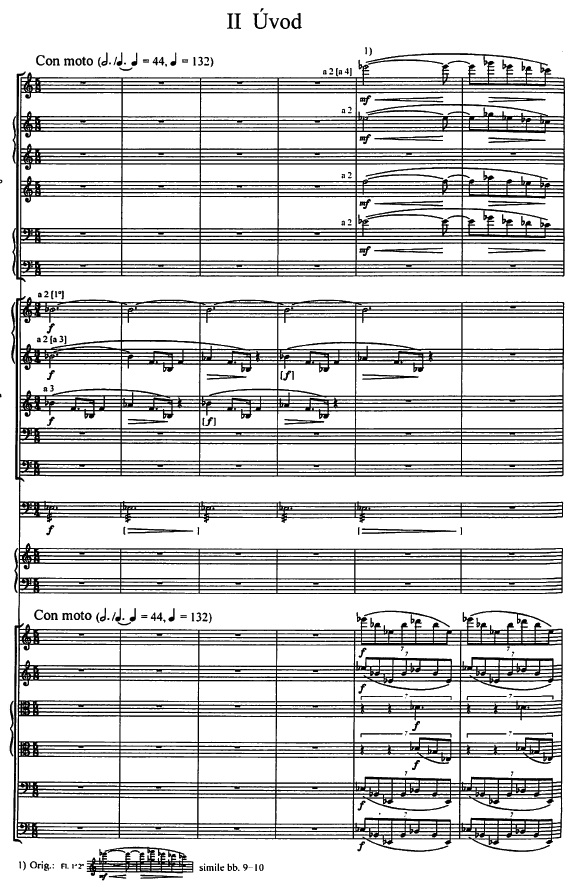

With all of the classical prototypes for musical minimalism that are so perennially trotted out – Perotin, the first six minutes of Das Rheingold, Bolero, Vexations and other Satie works – I’m surprised no one ever mentions the duet between Point and Elsie, “I have a song to sing-O,” in Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Yeomen of the Guard. The entire, rather long song is sung over a drone on D, and the verses follow a strict additive process, adding four new measures with each verse, somewhat akin to the early works of Glass and Rzewski:

This strikes me as a much more truly minimalist impulse than the Das Rheingold opening, which is nothing but a spectacularly long dominant preparation of a type Beethoven would have recognized. I suppose Gilbert gets credit for the additive process idea, since his lyrics necessitate it – and Sullivan carries it off so gorgeously. This I can accept as a minimalist prototype.

UPDATE: To stave off further ludicrously off-topic comments, let me clarify the context of this post. That Young, Riley, Reich, and Glass were inspired, in their early minimalist efforts, by John Coltrane, Indian music, African drumming, Ravi Shankar, and other non-European traditions is well documented. I have written many times, in many places, that minimalism was an irruption of non-Western influences into the Western tradition – even, American music’s attempt to connect with the rest of the world. This blog entry is not about the actual origins of minimalism.

This blog entry is about what I see as a simplistic tendency, which I’ve written about here repeatedly before, on the part of people who don’t know much about minimalism to identify various relatively static examples in the classical repertoire as precursors of minimalism. I find it ridiculous to think of Das Rheingold or Bolero as minimalist, but I did find this one G&S song to which I thought the term could legitimately apply. Perhaps, as Doug Skinner suggested, G&S were channeling some ancient Saxon archetype foreign to the European mainstream. I find this interesting as a comment on the occasional originality of G&S. Believe me, I am not sitting around wondering where the minimalists (Young, Riley, Reich, Glass) got their ideas and jumped on this song as the only thing I could think of because Western classical music is the only thing I know. I do not imagine that La Monte, Terry, Steve, and Phil started minimalism after seeing The Yeomen of the Guard together.