With some slight hesitation I post a new and rather comical work to the internet. It was supposed to be titled Triskaidekaphonia 2 because it uses the same tuning as my piece Triskaidekaphonia, but it turned out so programmatic that I couldn’t leave it with such an abstract title. So it’s The Aardvarks’ Parade (click to listen, just over ten minutes), in honor of an animal with which I had a childhood fascination. For the first time ever I’ve written a microtonal piece in a scale I’d already used before, and it’s the simplest one I’ve ever used: all the ratios of the whole numbers 1 through 13 multiplied by a fundamental, yielding 29 pitches. The form is AAAA: I was musing about a melody repeated over and over, in simple quarter-notes and 8th-notes, but so intricate in its tuning that several repetitions wouldn’t be enough to make it predictable. If I Am Sitting in a Room is the conceptualist Bolero, maybe this is microtonality’s Bolero. I tend to repeat things four times in my pieces: partly because it’s an American Indian tradition, paying homage to the East, West, North, and South, and partly because my first college composition teacher, Joseph Wood, told me that you could only get away with repeating something three times in a piece, instantly stirring my innate rebelliousness.

With some slight hesitation I post a new and rather comical work to the internet. It was supposed to be titled Triskaidekaphonia 2 because it uses the same tuning as my piece Triskaidekaphonia, but it turned out so programmatic that I couldn’t leave it with such an abstract title. So it’s The Aardvarks’ Parade (click to listen, just over ten minutes), in honor of an animal with which I had a childhood fascination. For the first time ever I’ve written a microtonal piece in a scale I’d already used before, and it’s the simplest one I’ve ever used: all the ratios of the whole numbers 1 through 13 multiplied by a fundamental, yielding 29 pitches. The form is AAAA: I was musing about a melody repeated over and over, in simple quarter-notes and 8th-notes, but so intricate in its tuning that several repetitions wouldn’t be enough to make it predictable. If I Am Sitting in a Room is the conceptualist Bolero, maybe this is microtonality’s Bolero. I tend to repeat things four times in my pieces: partly because it’s an American Indian tradition, paying homage to the East, West, North, and South, and partly because my first college composition teacher, Joseph Wood, told me that you could only get away with repeating something three times in a piece, instantly stirring my innate rebelliousness.

Some Composers Are Not Islands

I have to say, this has become one of the most richly fulfilling summers I’ve ever had. On one hand I’ve done all this work on piano recordings by Harold Budd and Dennis Johnson, plus a long John Luther Adams analysis I’m finishing and my Robert Ashley biography (3000 words written today, after hours of composing); on the other, recording my piece The Planets with Relache, and then a slew of music rushing out of me lately, with a ten-minute microtonal piece written this week (of which more soon), and two other new pieces begun in the same span.

Cage wrote a mesostic for Nancarrow that reads, “oNce you / sAid / wheN you thought of / musiC, / you Always / thought of youR own / neveR / Of anybody else’s. / that’s hoW it happens.” I think I probably could have been as reclusive as Nancarrow, had not economic necessity forced me into the public life of music criticism. But I certainly am not like Nancarrow in this other respect. A life exclusively focused on my own music seems unimaginable. My musicological work feeds my composition, and vice versa. When I’ve been doing too much critical work and not composing, I get cranky; and when I’ve been composing continuously, I dry up a little, and I start to need the interaction with the music of others. It’s not that I steal so many ideas from other composers, though of course I never scruple to do that. Nothing about the other people’s music I’m working on went into the piece I just finished, though I do absorb inspiration from the brilliant things Ashley says, and Budd always reconfirms my love for the major seventh chord. I just need that rejuvenation from other artist’s ideas, the mere presence of simpatico music I didn’t write.

I seem not to be unique in this respect among my close contemporaries. Larry Polansky, a far more prolific composer than myself, has done loads of important musicological work on Ruth Crawford, Johanna Beyer, and Harry Partch, not to mention running Frog Peak Music for the publishing of other composers’ music. Peter Garland, in between writing his own wonderful pieces, published the crucial Soundings journal for many years, and made available the music of many who didn’t seem so obviously important at the time as they do now. Some of us need this close interaction with the music of our contemporaries. Nor does it seem like just an American thing. Schumann certainly spent a lot of his career inside other composers’ heads, and seems to have enjoyed having a trunkload of Schubert’s manuscripts in his apartment, from which to draw for the occasional world premiere whenever he fancied. Liszt played the piano music of every significant contemporary except Brahms (who offended him by falling asleep at the premiere of Liszt’s B minor Sonata).

Part of it is what I think Henry Cowell sensed: that there’s no such thing as a famous composer in a musical genre no one’s heard of, and so one’s personal survival depends on a rising tide raising all boats. But Morton Feldman also tells a story of an artist in the ’50s who, after seeing Jackson Pollock’s first astounding exhibition of drip paintings, remarked, “I’m so glad he did it. Now I don’t have to.” And Feldman adds, for thoughtful emphasis, “That was not an extraordinary thing to say at the time.” Some of us do have this feeling that art is a collective activity, that it’s not all about ourselves. I hear an exquisite piece like John Luther Adams’s The Light Within, and I do think, somehow, “I’m so glad he did it, now I don’t have to” – partly because I want to hear that kind of ecstatic wall-of-sound genre, and he can so it much better than I could. Mikel Rouse’s music is so much more sophisticated than my intentionally naive fare, but listening to him gets me back on track. I listen to Eve Beglarian’s music, and I hear things I might have been tempted to do, but she’s got them covered. These aesthetically close colleagues free me up to pursue what I do best, but I somehow need to participate in their achievements by analyzing them and writing about them.Â

We Americans are taught to worship individuality, in art above all, but there is a strong collective aspect to creativity that many composers strenuously ignore or deny. I have no idea why I’m so attuned to it, especially being as anti-social as I am by temperament. But I do know that if anyone ever regrets that I had to write all these books and articles instead of working non-stop on my own music, they will have missed the point. It’s all the same thing.

A Cautionary Example

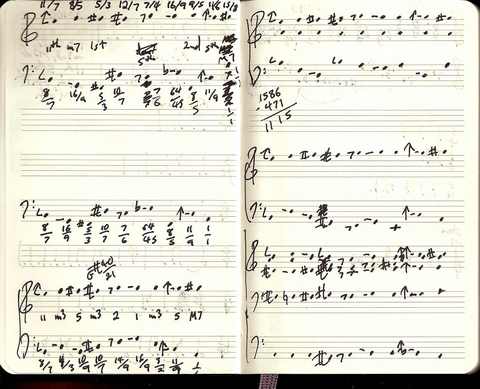

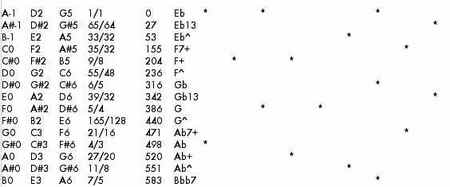

If you have a friend who’s considering becoming a microtonal composer, and you are frantic to spare him a life of agony and unfulfillment, I’m about to do you a big service: just have him read this. All day yesterday and this morning I spent hours filling my little sketch book with pages of notes and numbers like this:

The Composer’s Code of Polite Silence

I’m transcribing my interviews with Bob Ashley (kind of in shorthand, I don’t have time to do a real transcript; some student can do that someday if he wants). A name of one of Bob’s contemporaries would occasionally come up, and he’d give me a frank appraisal of the person’s music. Sometimes he’d asked me to switch off the tape recorder to do so, sometimes he’d instead hesitate a moment and then say, “You can put that in the book.” After one of those, he said, “There’s got to be somebody who says something about somebody.” Amen.

Ear-Driven Music

Composer David Bruce has an interview with me up on his Composition:Today web site.

Those Jangling High C’s on the Piano

What a pleasure it was to find Robert Carl’s new book about Terry Riley’s In CÂ (from Oxford) in my mailbox today (or actually, on top of it, which was poor judgment on the mailman’s part, since it’s rained here every day for the last month). I wrote a blurb for the back cover and shouldn’t say anything more, but I’m impressed once again with the smoothness and non-academicism of Robert’s writing style – I thought composers had to work for a newspaper for years to achieve that. Also with the number of people he interviewed in great detail about Riley’s early career, which is stuff that I’ll surely end up quoting. There are people I won’t have to interview because Robert’s already done it. It’s about time we had a book on In C, which was my generation’s Rite of Spring. My Long Night (1980), though quite opposite in atmosphere, was, formally, closely modeled on it. My only thought was, if some card-carrying musicologist had written the book, and Robert had written his Fifth Symphony instead, I would be twice as happy. Why is the musicology of new music (and not all that new at that) being left to us composers? It’s a question to bring up at the minimalism conference, at which Robert will be giving a keynote address.Â

What a pleasure it was to find Robert Carl’s new book about Terry Riley’s In CÂ (from Oxford) in my mailbox today (or actually, on top of it, which was poor judgment on the mailman’s part, since it’s rained here every day for the last month). I wrote a blurb for the back cover and shouldn’t say anything more, but I’m impressed once again with the smoothness and non-academicism of Robert’s writing style – I thought composers had to work for a newspaper for years to achieve that. Also with the number of people he interviewed in great detail about Riley’s early career, which is stuff that I’ll surely end up quoting. There are people I won’t have to interview because Robert’s already done it. It’s about time we had a book on In C, which was my generation’s Rite of Spring. My Long Night (1980), though quite opposite in atmosphere, was, formally, closely modeled on it. My only thought was, if some card-carrying musicologist had written the book, and Robert had written his Fifth Symphony instead, I would be twice as happy. Why is the musicology of new music (and not all that new at that) being left to us composers? It’s a question to bring up at the minimalism conference, at which Robert will be giving a keynote address.Â

Column #54

My profile of composer Julia Wolfe is out in Chamber Music magazine this week.

A Little Slow with the Index Cards

Speaking of Robert Ashley, I had a wonderful moment interviewing him a couple of weeks ago. We covered his entire life up to 1979, and then hit Perfect Lives. Of course I think Perfect Lives (then titled Private Parts) was the onset of the spectacular part of Ashley’s career, the moment at which he transcended the post-Cage conceptualist movement he was a player in. The piece will get an entire chapter in my upcoming book. And as we discussed it I learned that I had been involved in the world premiere. On October 24, 1979 – I have the poster for the performance in my living room – Ashley and “Blue” Gene Tyranny came to Northwestern University, at the invitation of my composition teacher Peter Gena, to perform Private Parts in its entirety for the first time. I had forgotten, if I knew then, that this was the first complete performance. Bob, as was his wont, needed a bottle of vodka to drink during the performance. As the grad student go-fer in charge, it was my job to drive in a rush to Desplains, Ill. (since Evanston, home of the Women’s Temperance Union, was a dry town) and buy the vodka. Vodka was a little heady for my taste at the time – a 1994 trip to Warsaw would change that – so, imitating my hero, I picked up a bottle of wine for myself. Bob was then performing the piece by reading the text from a video monitor. Technology being what it then was, the monitor was connected to a backstage camera, and someone had to hold index cards containing the text in front of the camera. That someone was me. So Bob was onstage drinking vodka, “Blue” was playing the piano in his inimitably gorgeous way, and I was backstage sipping wine while moving cards in front of a video camera. At one point late in the piece I was a little slow, and I heard Bob patiently say, in the middle of the text, “Kyle….”Â

Young Avant-Gardists at Play

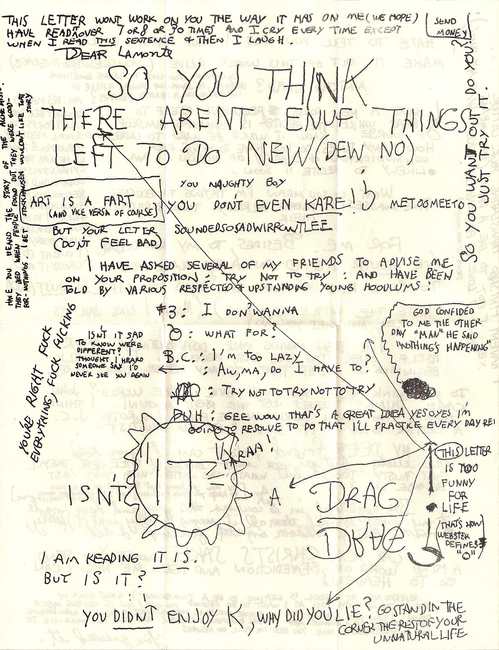

Anyone remember this?

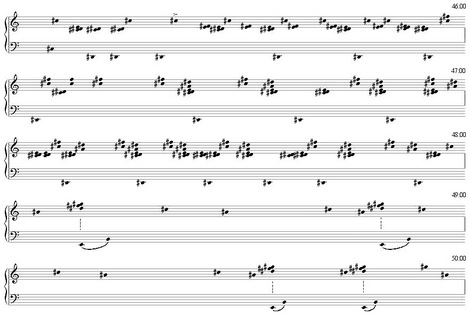

Notating Dennis

And here’s an mp3 of this passage in the original 1962 recording so you can compare. (I suppose you might have to reopen Postclassic in an additional browser window to listen and follow along at once.) This is one of my favorite moments in the performance, where the relatively dense (by ’50s minimalism standards) section on the dominant of G# minor gives way to a kind of beatific deceptive cadence and much slower material. Each section of the piece, each tonality, has its own atmosphere and tempo that seems drawn from the intervals played around with.

And that’s the problem: you can’t gather that from the original notation. The first three systems above are all drawn from this little bit of Johnson’s score labeled IIIa and IIIb:

Wherever this material recurs, it’s the fastest part of the piece, with a kind of anxious melody leading down from F# to D# to C#. In some notes he apparently made later in the 1980s, Johnson singles this material out to try to figure out what his logical process was, which was a kind of ABACABACDCDB, and so on, among closely related figures. The E major material that follows, on the other hand, doesn’t appear in the manuscript score at all. The piece is intended to be improvised from the scores, and needn’t duplicate the tape; in fact, an alleged four hours is missing from the tape. So neither the score nor the tape is sufficient to construct a performance. Using the score, a pianist could play the work, but only after considerable study of the available 112 minutes on the tape, to find out how Johnson moved from one section to another and how he characterized the material in each section. It’s a peculiarly hybrid form of improvisation, in which you’re limited to what’s on the page, but the page isn’t enough. Hopefully my transcription will yield up enough analytical insight to resurrect some version of the whole thing.