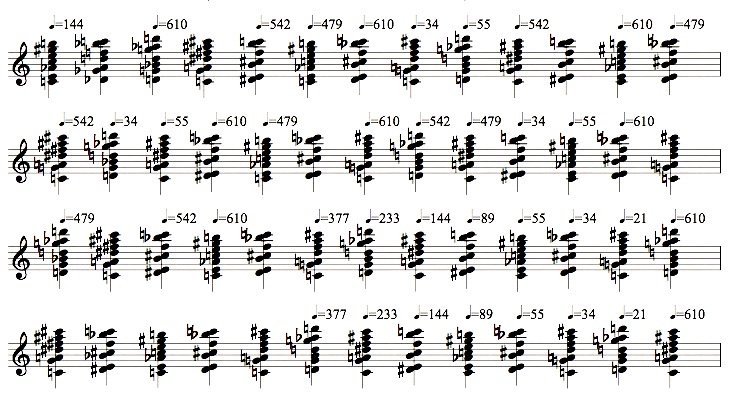

A brief new tuning study for the 232-key piano of my imagination: Romance Postmoderne. As I was playing it, my wife said, “Boy, the pitches in that are really bendy.” Then she looked at me suspiciously and added, “You can’t hear it, can you?” And I had to admit I couldn’t. It sounds so normal to me; I’d love to hear how weird it sounds to other people, but I’ve just grown too accustomed to thirteenth harmonics. The tuning is really elegant, all harmonics of Eb: the odd numbers from 1 to 15 multiplied by each other, an 8 x 8 grid comprising 33 different pitches once the duplicates are accounted for (7 x 11 = 11 x 7, for instance). In other words, eight harmonic series’ each up to the 15th harmonic, based on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th, 13th, and 15th harmonics of Eb. Hate the piece if you want, but admit that if musicians could learn to hear these intervals, there’d be enough new material here to invigorate new music for at least the next century. UPDATE: complete tuning chart here.

AFTERTHOUGHT: The main difference between this and impressionism, or bebop harmony, is that there are fewer pivot notes between chords. Except for the 3rd harmonic (V chord), which is a special case and I don’t use it much, any two (potentially eight-note) chords tend to contain only one pitch in common. Of course, the result of that is parsimonious voice-leading heaven.

(Incidentally, I tried to turn the file into an mp3 in iTunes, as usual, and the aiff – which had sounded fine when I made it in Logic – got all distorted. I looked around the internet and found that everyone’s complaining about distortion in iTunes in the latest Mac OS. I had to find an internet audio converter to change the file. What a pain. Damn you, iTunes!)