One of my sabbatical-and-summer goals, which I have now achieved, was to finish five out of the fifteen chapters of my book on the Concord Sonata. In particular, I wanted to finish the analytical chapters on “Emerson” and “Hawthorne.” Between them those two movements account for more than 3/4 of the sonata’s pages, and by far the most complex ones as well; comparatively, “Alcotts” and “Thoreau” will be a snap. If I could finish “Emerson” and “Hawthorne,” I thought, accounting for every measure and system – and I have, with 14,000 words and 80 musical examples in the “Hawthorne” chapter alone – then the rest of the book will fall into place. I’m waiting to hear back from a publisher, and I could go on and on about about neat things I’ve found, but this is going to take a couple of years and I don’t want the information pre-empted, even by myself. Thus, partly, my recent uncommunicativeness.

One thing I’ve been realizing, though, is how much we need a new performing edition of the Concord. Ives published two editions, in 1920 and in 1947, with quite a few changes between them. A lot of dissonance was added to “Emerson” in particular, but, as Geoffrey Block has shown in his article “Remembrance of Dissonances Past” in Philip Lambert’s Ives Studies, the bulk of it was restoring dissonances that Ives had omitted from the first edition as possibly seeming too radical. (Specifically, many of them were dissonances in the orchestra part of the discontinued Emerson Concerto from around 1909.) So much, once again, for the idiot charges about Ives “modernizing” his music after the fact, may they rot in music history’s dustbin.

Theoretically, my object is to analyze the 1947 score in every detail, but I keep running into deviations between that score and the recordings I’m familiar with, especially John Kirkpatrick’s, which I’ve known for 43 years. For instance, there’s a passage at the end of “Hawthorne” where the “Human Faith” theme returns in an abstract thicket of notes at the middle of page 47, with a couple of chromatic oddities thrown in (left hand):

The normal version of the theme wouldn’t have the D-natural, and the final G’s and A’s would be sharp. This next example is how it appears in the manuscript, and how Kirkpatrick plays it in both his recordings, 1945 and 1968:

OK, so Kirkpatrick didn’t like some of the 1947 changes, and in fact, refused (uncharacteristically) to help Ives prepare the new edition because of it. But in the copy of the 1920 score that Ives used to make the changes for the 1947 score, I can find where Ives did indeed add naturals to the second (tied-over) D, but I can’t find any naturals on the G’s and A’s – and Ives caused a lot of problems, all through the sonata, by sometimes canceling accidentals and sometimes not, usually assuming that they shouldn’t carry over but occasionally, it seems, forgetting. So I don’t feel at all confident that the naturals in 1947 are right. I can imagine, at this kind of hairy point in the movement where all is chaos, maybe he really wanted a weird, chromatically distorted version of his main theme. But certainly in the first draft he wanted it the way Kirkpatrick plays it, and I can’t, myself, trace the process through the manuscripts that led to the 1947 alteration. Meanwhile, we know that Ives himself liked to play the piece differently every time he sat at the piano, so there’s plenty of rationale for taking liberties – but the present score only gives one version, and how many pianists get to go through all the sources and see the different versions? It would certainly be nice to have an edition that includes all the reasonable ossias.

A worse problem has to do with the quotation of the hymn Martyn in F# on page 34. In both 1920 and 1947 versions, it’s just triads in the key of F#. But many of you will recall that Kirkpatrick adds a lot of little dissonant “shadow” thirds as afterbeats:

Again, Ives didn’t print these thirds in either score. Some of them – the first few – are included on one of his manuscript pages, along with some other variations that didn’t fly. (Next to those thirds he wrote “angels of our” and the next word looks like “inarla” – but could be “nature”? A Lincoln reference? But if so, why?) More of them, but only single notes, not thirds, are included in the version of this passage that got drafted into the second movement of the Fourth Symphony. A few of them, but also some very different lines, went into another piano piece based on “Hawthorne,” The Celestial Railroad. Kirkpatrick adds them tastefully, they sound consummately Ivesian, and I’m so used to his recording that I’m disappointed when I hear a recording that omits them. But while Ives certainly toyed with the idea, I can’t find a manuscript with textual evidence for the specific ones Kirkpatrick plays. So I feel kind of guilty now when I hear them – they’re so beautiful, and Ives clearly thought about them, but after a quarter-century of planning a new edition of the Concord, he equally clearly decided not to add them.

As for the pianist who wants to add them, where will you find a text? Well, I took these down in dictation from Kirkpatrick’s 1968 recording, but Kirkpatrick also produced his own hand-written private performance edition of the Concord, which I’ve seen. (Not a printable option: he puts in meters everywhere, and the Ives scholars are trying to roll back what’s seen as Kirkpatrick’s too-free hand with the Ives scores.) Among the recordings I have, Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Nina Deutsch, and Robert Shannon play some of these thirds, but fewer than Kirkpatrick and not always the same ones; and most of the other pianists stick to the score and omit them. So a good, new performance score should offer some guide to including them, since they’re now so much a part of the tradition – but which text to use? How many different possibilities? The hell of it is, Ives probably would have found any solution acceptable, but a good performance edition should offer guidelines as to what the options are. As it is, you can’t really prepare an authentic performance of the Concord, it seems, without doing your own research at the Yale library.

No new edition is in the works, and I’m ambivalent – I’m very specifically keying my analyses to the 1947 edition, and a new one that was paginated differently could render my book obsolete. You just can’t use measure numbers with this piece, because there are so few bar lines. Ives sure knew how to make things difficult and ambiguous.

(And yes, I know all about Ives’s house in West Redding being up for sale. Sad story, very expensive land, the huge sums it would take to save it aren’t forthcoming. I feel even sadder that the Ives birth-house in Danbury, which I visited and toured so many times, is literally falling down. Seems nothing can be done. Not being a one-percenter, I try not to think about it and think about the Concord manuscripts instead.)

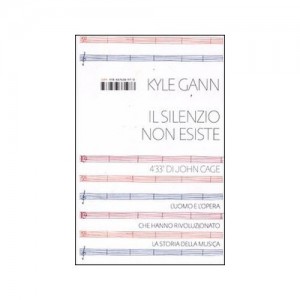

Apparently “The Silence Does Not Exist” (as Google retranslates it)

Apparently “The Silence Does Not Exist” (as Google retranslates it)