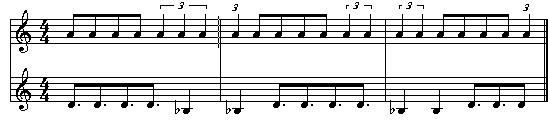

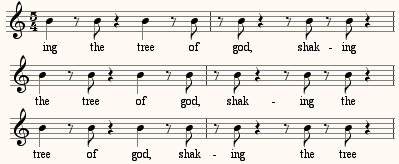

In my extensive post on Metametric music (you know, The Style Formerly Known as Totalism, c’mon, man, get with the program) I mentioned that I could never figure out how the California Ear Unit performed the three meters at once of Art Jarvinen’s Murphy-Nights. To save you from having to look, the piece starts off with an 8/4 ostinato (32 16th-notes) in the electric keyboard against a 33/16 ostinato in the electric bass – on top of which the rest of the ensemble enters in changing meters, starting in 6/4. (You can hear the effect here.) I wish I could show you the actual score: in its postminimalist way it’s as scary as any early Stockhausen outside of Gruppen. I’ve known Art for years and could always have asked him how they did it, but sometimes when I’m amazed by something I enjoy not knowing the secret, and just letting my imagination run wild. Well, Art decided to dispel my imaginings, and I provide his explanation – which will ring familiar, I think, to every composer/performer who has performed in his or her own chamber music. The trick, he says, was

rehearsal, mainly. But some other factors played in.

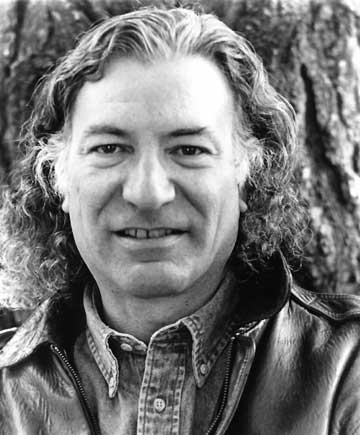

First of all, it’s just not that hard for the melody instruments to lock into the keyboard, which is in straight 8 – might as well be four-four. The bass is the one that has to be on his toes, and that was me. When I came up with the idea, I test drove it at home, playing bass over a tape of the keyboard part. No problem. Knowing I could hang with it, the rest of the group just had to follow the keyboard, and trust me to be with them at the next big downbeat. We played the piece live exactly 14 times, and no, we didn’t always get it right, but we did most of the time. For the recording we put down bass and keyboard together first. That was the only take (he said somewhat proudly, but not smugly). It was such a treat to work every day with such great players.

Almost the whole group had a couple of advantages over most conventional players such as orchestra section players. We had played a LOT of Reich, as well as Michael Gordon, Andriessen, etc. We cut our teeth on music made from these sorts of schemes. And of extreme importance I would add, is that most of us played in rock/jazz/pop bands, and understood groove as a collective thing, not just accuracy within one’s own part. The one time we had some difficulty getting the piece to work was when we broke in a new keyboardist. Fabulous player, but zero pop music experience. Even played “accurately” the groove wasn’t happening. So we had a sectional with just bass and keyboard, with clarinetist Jim Rohrig coaching the keyboardist on feel, not counting. It all came together again pretty quickly after that.

Back when I used to perform in my own ensemble pieces, I’d write rhythms in my own part that I wouldn’t have dared put anyone else through, and also left parts blank to fill in in performance. Art also adds commentary to my post on Lucky Mosko’s music:

You definitely zeroed in on a couple of major issues, things he was consciously trying to do, such as sabotage the listener’s sense of temporal placement. His succession of “nows” forms a coherent continuum – of sorts – but it’s not a “classical/logical” formal argument he makes. I always thought of all of Lucky’s pieces as “middles” of a much larger, eternal, piece, that we are given samples of now and then. None of his pieces really start or end. They just happen.

While I’m at it, I was about to say (before Samuel Vriezen anticipated me) that I could imagine making a distinction between metametric music and totalism. Part of the idea of totalism, beyond the rhythmic issues, was that it brought together elements from rock, jazz, and world musics, and also appealed both to pop music fans and postclassical fans. The term metametric focuses in on just the rhythmic angle, and (since coined by a Dutch composer in response to an American style) could indicate a broader realm of music, defined more technically and less by style and milieu. Don’t goad me on this, you don’t want to know how anal I can get when it comes to defining musical terminology.

I had never heard Mosko’s music, but was well aware of his activities as a conductor. I once reviewed his Newport Classic recording of Feldman’s For Samuel Beckett as being the best available. Last week Art Jarvinen was kind enough to send me the O.O. Discs CD of Mosko’s music, performed by the California Ear Unit, and he tells me there’s a hard-to-find one on Cambria as well. I had no idea what to expect. Mosko’s music is thorny – or gnarly, in the parlance of our time – but his time sense is distinctive. Even when the music’s individual gestures are quick, it sustains its focus for many moments in succession, and changes slowly. It is quasi-atonal in a way that allows tonal passages to happen in a non-quotation-like way, almost as if it simply makes no distinctions among sonorities. Therefore it is playful rather than tense, with highly soloistic instrumental writing, and reminds me, more than anyone else, of Stefan Wolpe’s music. There is much stasis, dotted by delicate bursts of activity that build up no momentum. His early influences include Webern, Feldman, Cage, Icelandic folk music, and Sufi music, the first three more evident than the others.

I had never heard Mosko’s music, but was well aware of his activities as a conductor. I once reviewed his Newport Classic recording of Feldman’s For Samuel Beckett as being the best available. Last week Art Jarvinen was kind enough to send me the O.O. Discs CD of Mosko’s music, performed by the California Ear Unit, and he tells me there’s a hard-to-find one on Cambria as well. I had no idea what to expect. Mosko’s music is thorny – or gnarly, in the parlance of our time – but his time sense is distinctive. Even when the music’s individual gestures are quick, it sustains its focus for many moments in succession, and changes slowly. It is quasi-atonal in a way that allows tonal passages to happen in a non-quotation-like way, almost as if it simply makes no distinctions among sonorities. Therefore it is playful rather than tense, with highly soloistic instrumental writing, and reminds me, more than anyone else, of Stefan Wolpe’s music. There is much stasis, dotted by delicate bursts of activity that build up no momentum. His early influences include Webern, Feldman, Cage, Icelandic folk music, and Sufi music, the first three more evident than the others.