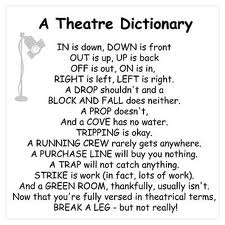

The Theatre Development Fund has launched a whimsical online resource called Theatre Dictionary.

The tool is being billed as “a video guide to ‘theatre lingo’ by TDF and theatre companies from across North America.”

Clearly a lot work has gone into developing the resource.

It comprises mostly lighthearted one-minute-long-ish videos explaining terms like “fight director,” “hybrid theatre” and “fourth wall”, along with written essays providing more background on each term.

There’s also an interactive element where users can submit their own definitions and videos, making the whole thing kinda like a Wiki for the stage.

I’ve been spending some time with the Theatre Dictionary this morning. In principle, it provides a fun, low-barrier-to-entry way of demistifying the art form for a general audience. But the quality of the videos is patchy.

I love the one about “The Scottish Play,” which features a pair of actors at Soho Rep in New York talking about how much they like playing witches, and just as they’re about to utter the title of the cursed Shakspearean tragedy, another actor pops up and stops them. This leads to a funny explanation of what will befall the thespians if they utter the word. Similarly entertaining is the video about “Peas and Carrots,” the term for the gibberish uttered by actors chatting in the background of a scene, while the main action / dialogue is being played out in front.

What’s far less compelling, however, is the video describing “black box theatre.” It features a slide show of photographic stills taken in black box spaces and narration by a guy with a droning voice. The drone may be intentional, perhaps to conjure up the concept of an “empty space” devoid of life. But its monotony exceedingly grates on the nerves.

I am looking forward to seeing the Theatre Dictionary grow and thus increase its usefulness. There’s still much work to do in terms of adding more content. The site is a bit thin right now. I guess that’s where the user-generated aspect of the resource will come particularly in handy.

However, even in its current form, the tool is still provides a much more tactile way of explaining theatre terms than the standard theatre lexicons that exist in print and online.