The words theatre and magic are often seen in the same sentence, even though the two genres place very different demands upon audiences’ understanding of reality that are often difficult to reconcile.

In most forms of theatre, audiences understand that they are witnessing a make-believe world, but choose to suspend their disbelief in order to enter fully into that world and potentially be transformed by it.

Magic, by contrast, requires audiences to completely buy what they’re seeing on stage as hard reality: They have to be convinced that it is truly possible to saw people in half and put their bodies instantly back together again, or for an illusionist to read the secrets of their minds.

That being said, Shakespeare’s The Tempest is one of the few plays I can think of that comes tantalizingly close to uniting magic and theatre together into one seamless whole.

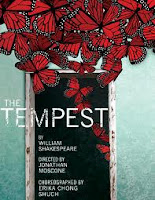

This feat is very much in evidence in Jonathan Moscone’s incandescent new production of Shakespeare’s late Romance at the California Shakespeare Theater, which makes (mostly) carefully calculated demands on both our suspension of disbelief and complete buy-in to an alternate reality.

The most magical quality of the production is its Ariel, Erika Chong Shuch. Shuch is a Bay Area-based dancer and choreographer (she also created the movement sequences for this show.) This is Shuch’s first Shakespearean acting job. But the fine-featured performer executes the role like she was born to play it.

Shuch’s is a very human Ariel — she clearly loves Prospero like a father and we often see her struggle to weigh up the benefits of obeying the old man’s orders and getting impatient with him for stringing her along.

Balanced against this is the physical joy of Schuch’s movement. Aided by fellow sprites, she takes off and twirls around in the air and leaps elegantly from one stack of tattered books to a bit of crumbling boat on Emily Greene’s salvaged wreck of a set. This is what gives the production its uncanny sparkle.

One aspect of the production that adds to the magic is Moscone’s decision to double many of the parts. Doing so obviously comes with economic benefits as there are only nine actors in the production (and three of these are non-speaking sprite roles). But the decision also makes sense in terms of the world of the play.

By having Catherine Castellanos play both Caliban and Sebastian, Nicholas Pelczar take on Ferdinand and Trinculo and Michael Winters perform Prospero and Stephano, the concept of power — who holds it and why — is turned on its head. Power becomes something fleeting and coincidental: He that plays a king in one scene plays a pauper in the next. Magic seems to be the only rational explanation for anyone’s status in life.

But every now and again, the qualities that anchor the theatrical and the

magical in the production come un-moored in a sea-sick inducing way.

The doubling of parts poses particular challenges on the audience’s ability to suspend its disbelief and immersion in the magical “reality” of the story towards the end of the drama.

In the “big reveal” at the play’s conclusion, some inelegant transitions made me fearful about how Emily Kitchens, as Sebastian, would be able to suddenly turn herself into Miranda. I felt the same discomfort regarding Nicholas Pelczar who takes on Trinculo and Ferdinand “all at once.”

The characters didn’t end up having to talk to themselves, thank sprite, but they came uncomfortably close to having to do so. Thus isn’t the kind of stage illusion-making that Shakespeare was shooting for.

Michael Winters’ disappointingly dull Prospero also hampers with our ability to “stay in the play.” Besides bringing little in the way of electricity to this most electrifying of Shakespearean leading roles, the actor struggled with his lines on opening night, creating a knot in my stomach. At one point, Kitchens had to feed Winters a line. And he came close to causing a shipwreck with his character’s famous “Ye Elves…” speech. I would have much rather seen James Carpenter do the role.

Still, getting pulled away from the play is mostly a fleeting issue in this production. In this Tempest, magic and theatre still fly together strong.