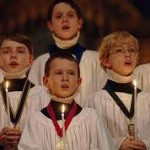

I learned something new last night during an interview about boychoirs for VoiceBox, the weekly public radio program on KALW 91.7 FM, podcast series and website which I host and produce all about the vocal arts:

I learned something new last night during an interview about boychoirs for VoiceBox, the weekly public radio program on KALW 91.7 FM, podcast series and website which I host and produce all about the vocal arts:

My in-studio guest for the show, Kevin Fox, the founder and director of the Pacific BoyChoir Academy in Oakland, said that in the UK, people talk about boys’ voices “breaking”, whereas in the US, they talk about the voices “changing.”

Why should this apparently subtle difference in semantics matter any more than the contrast between referring to the back storage compartment of a car as a “boot” or “trunk” or the pedestrian walkway of a street as a “pavement” or “sidewalk”?

According to Kevin, there’s a world of difference between referring to the male voice as being in a state of “breaking” or “changing.” More than a semantic distinction, it explains a difference in attitude towards boys’ voices between the two vocal traditions.

Apparently, in the UK boychoir scene, boys are generally sopranos. They typically do not get trained as altos. Those parts are handled by grown male countertenors. The word “break” acknowledges this dramatic shift from soprano into the adult vocal terrain.

In the States, however, boys typically perform both as sopranos and altos. Grown males sing tenor and bass. As a result, choral instructors see the development of the voice downwards as a process that happens over time, rather than a sudden inability to sing a high part effectively. It’s not uncommon for boys move between several different parts until their voices settle. Hence “change” rather than “break.”

I wonder if this difference in word choice speaks in more profound ways about the contrasts between Anglo and American culture?