Erwin Helfer, the 84-year-young Chicago pianist of heartfelt blues, boogie, rootsy American swing and utterly personal compositions, has told his tale of covid-19-related profound depression, hospitalization, treatment and recovery to the Chicago Sun Times. I’m a longtime friend, ardent fan and two-time record producer of Erwin’s, and had lunch with him soon after the article […]

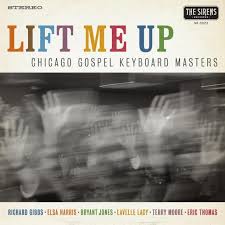

Gospel (not my usual bag) keyboards revelations

I’ll never be an avid fan, much less an aficionado, of gospel music — but Lift Me Up, Chicago Gospel Keyboard Masters, new from The Sirens, a local independent label, is clearly full of joy and inspiration. It also is notable for documenting a seldom spot-lit but obviously thriving American roots music scene. Art arising from or meant to beget religious transcendence […]

Earma Thompson, unheralded piano jazz star, dies at 86

A Chicago mainstay, whose efforts supported local and touring musicians starting in the early ’40s but who didn’t record under her own name until 2004, Earma Thompson deserves to be celebrated as an outstanding example of how women have participated in jazz often more than is acknowledged, from behind the scenes. As the Chicago Tribune’s […]