Creative Capital and the Warhol Foundation have an idea I adore: Offer grants “directly to individual writers . . . Â in recognition of both the financially precarious situation of arts writers and their indispensable contribution to a vital artistic culture.” From the Request for Proposals: The program, which issues awards for articles, blogs, books, new […]

Rhymin’ Simon swings $3.6 mil Wynton’s way

Jazz at Lincoln Center has released a “Post Gala Report” on the April 18 concert debut of Paul Simon performing his career songbook with both his band and the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis, plus special guest vocalist Aaron Neville. Â $3.6 million was raised at the black tie event, which provided dinner and […]

Limor Tomer: Principles for curating performance at the Met Museum

My new City Arts column is reviews of newly released recordings by Henry Cole and the Afro-Beat Collective, Steve Lehman Trio, Less Magnetic, Esperanza Spalding, Michael Bates and Wayne Escoffrey. You may have to pick up a hard-copy of the paper for that. But the issue also features my interview with Limor Tomer, the Metropolitan Museum’s recently appointed […]

Jazz close to home: Community blogathon entries start on Jazz Day

My Brooklyn neighborhood, called Kensington, is full of musicians, because residences are large and still semi-affordable. So I hear the guitarist across the street get excited while practicing, run into NEA Jazz Master pianist Kenny Barron when walking to the bakery and go to Sycamore, a flower shop-bar with basement recital room where  on Sunday […]

Dr. John w/ Black Keys’ Auerbach in Brooklyn Acad Music

Locked Down is The Black Keys guitarist-songwriter Dan Auerbach’s collaboration with Mac “Dr. John” Rebennack — the two premiere it April 5 – 7 at Brooklyn Academy of Music, second program of three the good Dr. presents there over three consecutive weekends. I bet it’ll be a better-produced show than his “Tribute to Louis Armstrong,” the […]

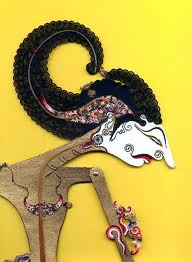

Shadow puppet and Javanese gamelan video now viewable

A followup: the Asia Society posted the  entire video of the  3.5 hour wayang kulit (shadow puppet and Javanese gamelan orchestra performance) that I wrote about Sunday — the one in which President Obama stopped by — in five parts. And colleague Richard Gehr wrote up the event for the Village Voice blog. howardmandel.com Subscribe by […]

Obama at Javanese shadow puppet show, Asia Society

President Obama made a surprise cameo appearance at the Asia Society’s production of a Javanese shadow puppet show  — a Wayang Kulit — by dhalang Ki Purbo Asmoro with Gamelan Kusuma Laras on Manhattan’s upper east side on Friday night (March 16). As a translucent strip of water buffalo hide, upright if not as nimble on his tusk-bone rods […]

Herbie Hancock, keytar master

The Herbie Hancock who concertized at Jazz at Lincoln Center last Saturday night was the casually joking yet research-minded fusion meister. A review of his Friday night concert by Jon Pareles in the New York Times takes a generous view of Hancock darting among his multitude of possibilities, but I was less taken by his […]

Which Herbie Hancock comes to Jazz at Lincoln Center

Pianist Herbie Hancock is a chameleon — as I say in my newest column in CityArts-New York. For his first appearance at Jazz at Lincoln Center on Friday night (3/9 ) he leads a trio, and on Saturday (3/10) adds Benin-born guitarist Lionel Loueke,  in formats a far cry from The Imagine Project, Hancock’s latest album. […]

Composer Heiner (Brains on Fire) Stadler @ It’s Psychedelic Baby

Heiner Stadler is a lesser-known but fascinating New York City-based composer who’s stretched he structures and dimensions of jazz with all-star productions including A Tribute to Monk and Bird and Brains on Fire (which I annotated for recent reissue). It’s Psycheledic Baby, the online magazine by Klemen Breznikar taglined “discover the unknown” has published an interview with Stadler — a Polish-born (’42) WWII refugee who heard a […]

The President sings his hometown blues

President Obama is not to be forgiven for signing the heinous Nat’l Defense Authorization Act and several other bad moves, but as a blues fan I give it up to the guy for singing “Sweet Home Chicago” with B.B. King while hosting the first ever  White House blues party. Obama’s version of Al Green’s “Let’s […]

Swiss jazzers occupy the Stone, East Village

European jazz stars of the Zurich-based record label Intakt come to the Stone, John Zorn’s serious recital room, for a two-week fest March 1 – 15 in which they’ll collaborate with veterans of NYC’s downtown improv scene. I detail some of the shows — and why people think jazz is better loved abroad than at […]

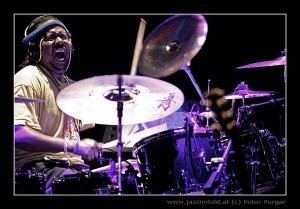

It ain’t easy playing Mahavishnu, but Weston does it

Guitarist John McLaughlin‘s Mahavishnu Orchestra was the highest-flying of any ensemble emerging from Miles Davis’ jazz-rock initiative in the early 1970s, establishing a previously unapproached standard of virtuosity, improvisational excitement and commercial success for all-instrumental electric bands to follow. Drummer G. Calvin Weston‘s Treasures of the Spirit quintet playing music of McLaughlin’s MO at the 92nd […]