Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. weekend ’18 was a big one for jazz in NYC with the first Jazz Congress at Jazz at Lincoln Center, a glorious Winter Jazz Fest, artists showcases at the conference of APAP (the Association of Performing Arts Presenters) and diverse independent venues — but not least of all the first […]

International Jazz RIPs, 2017

Photographer-writer-author Ken Franckling has painstakingly compiled a compendium of more than 400 jazz artists and associates from around the world who died in 2017, with links to obituaries of most of them. Posted at JJANews.org. It’s a striking document and useful resource, though Franckling says, sadly, “The list seems to get depressingly longer each year.” Maybe that’s […]

Celebrating Chicago pianist Willie Pickens (1931-2017)

Pianist Willie Pickens, 86, a powerful, lyrical and generous modernist who performed, taught and mentored young musicians from Chicago starting in 1959, died of a heart attack on Dec. 12 while at Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City, readying himself to play at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola with 29-year-old trumpeter Marquis Hill. Having heard […]

Hyde Park Jazz Fest, summer’s last dance (photos)

Chicago’s Hyde Park Jazz Festival in the first days of fall (Sept. 23 & 24th) which were unusually hot, is an exceptional event, curated for creative artistry, local and otherwise, drawing a highly diverse crowd to a fair that mixes popular and specialized performances at a range of boutique venues. Produced by an independent 501c3, the 11-year-old Hyde […]

Jazz community upends Englewood’s bad rep

The 18th annual free Englewood Jazz Festival in south side Hamilton Park last Saturday (9/16) affirmed the best of Chicago’s grassroots culture, promoting an opposite image of this challenged neighborhood as a dangerous place — unless one fears powerful, creative music that speaks as directly as dance rhythms to its family of listeners. Produced on behalf of the Live […]

My Q&A for Blues@Greece & Spirit of Jazz Award

Jazz, blues, American literature and where I’d go for a day in a time machine are topics I address in an email interview with Michalis Limnios who blogs at Blue@Greece. I post this item out of sheer vanity, reinforced by my being presented with a Spirit of Jazz Award tomorrow (9/16) by the Englewood Jazz […]

Youssou N’Dour on stage & screen, PoKempner photos

Photo-journalist Marc PoKempner‘s images from the Chicago Jazz Fest, as featured in my previous post, and these from Senegalese superstar Youssou N’Dour’s rousing who two weeks earlier, exhibit how he’s dealing straightforwardly and creatively with the screen backing musicians at the Pritzker Pavilion of Millennium Park. Giving us eyefuls to enjoy. Here’s what we can […]

Jazz on Millennium Park’s big screen – PoKempner photos

A 40-by-22½-foot LED screen is a dominating feature of the stage in the Pritzker Pavilion of Chicago’s Millennium Park, difficult to ignore though many try. Photographer Marc PoKempner does the opposite in his shots from the 39th annual Chicago Jazz Festival: he uses what he (and everybody else) sees to create striking images, in the […]

Chicago Jazz Fest expanded review & Deutsch photos

My DownBeat review of the 39th annual Chicago Jazz Festival held over Labor Day weekend in and spilling out of Millennium Park, highlights the best I heard — including the specially organized big band led by trumpeter Jon Faddis, making big fun from his mentor Dizzy Gillespie‘s fresh-as-fire arrangements dating 60 to 70 years back. (Gotta wonder what a […]

Jazz/Improv Chicago: Wide-ranging talents, free fests, PoKempner pix

Chicago’s jazz/improvised music scene contains multitudes, last week ranging from the wild yet earnest Liberation Music Collective to veteran piano sophisticate Michael Weiss in trio, as two of Marc PoKempner‘s photos document (and more of his vision, focused on links between local music and politics — Obama included — is on exhibit titled “Harold’s Got […]

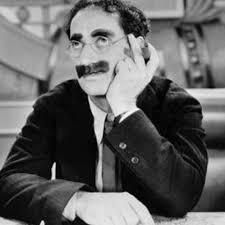

War for laughs: Marx Brothers, Strangelove, Chaplin, Lehrer

My father taught me at age 8 to trust the Marx Brothers’ for trenchant social commentary. Here’s Groucho, Chico, Harpo and Zeppo in Duck Soup. On the night of my 17th birthday I sat in a theater, alone, watching the incomparable Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb . . . Thanks […]

The Jazz & Blues Art Box — instant collection, rare data trove

Two hundred and thirty dvds of concerts and 96 interviews from the International Jazzfestival Bern (Switzerland), 1983 to 2002, 20 yearbooks plus a 344-page large format graphics-rich volume, in a cabinet on wheels standing almost 4 feet tall, 3 feet wide, 15 inches deep. Released as a one-time-only edition with a promise of no reissues and […]

Great new jazz photography: Sánta’s faces of Northsea Jazz Fest

The faces of jazz musicians Sánta István Csaba hears, sees and snaps are indelibly expressive — like the memorable phrases, inspired improvisations and magical connections these players play, so meaningful to listeners in the moment, remembered or recorded. JazzTimes magazine has published some of Sánta’s images from the Northsea Jazz Festival in early July — here are […]