European jazz stars of the Zurich-based record label Intakt come to the Stone, John Zorn’s serious recital room, for a two-week fest March 1 – 15 in which they’ll collaborate with veterans of NYC’s downtown improv scene. I detail some of the shows — and why people think jazz is better loved abroad than at […]

Archives for 2012

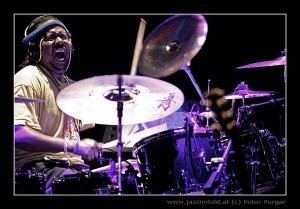

It ain’t easy playing Mahavishnu, but Weston does it

Guitarist John McLaughlin‘s Mahavishnu Orchestra was the highest-flying of any ensemble emerging from Miles Davis’ jazz-rock initiative in the early 1970s, establishing a previously unapproached standard of virtuosity, improvisational excitement and commercial success for all-instrumental electric bands to follow. Drummer G. Calvin Weston‘s Treasures of the Spirit quintet playing music of McLaughlin’s MO at the 92nd […]

Goin’ on about “free jazz” and “the avant-garde”, w/playlists

Jose Reyes of the online listening station Jazz Con Class has posted  a Q&A with me about “free jazz” and “the avant-garde” — which he proposes as two distinct subgenres of jazz, tied to the 1960s. New things — innovations — thinking outside the box — breaks from conventions and the continuum of progress (evolution) — these […]

American novels: as fun to write as they are to read?

Of 10 American novels critic Terry Teachout posted yesterday that he wishes he’d written, only All The King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren similarly appeals to me. I can imagine hunkering down as Penn Warren did, dryly but fiercely etching the sickness of American populist politics, which we’re seeing swirl at its sickest this very  primary season. It would […]

Lone wolf sax composer Tim Berne peddles Snakeoil

Alto saxophonist and staunchly original composer-bandleader Tim Berne’s new album — his 41st, but first on a label as internationally prominent as ECM since he put out two scorchers for Columbia in the mid ’80s — has the strange title, Snakeoil, meaning b.s., originating in the sale of quack medicines. This must be part of […]

“Organ Monk” weds funk & Thelonious, soul and smarts

Organist Greg Lewis, wearing a monk’s robe, plus guitarist Ron Jackson and drummer Damion Reid, tore up with full respect the knotty compositions of the late great Thelonious Monk last night at 55 Bar in Greenwich Village. About a dozen people heard them over a 90 minute period (they played a full set, took a break and performed […]

Etta James and Johnny Otis — Jazz Masters?

Etta James, who died today Jan. 20 at age 73, and Johnny Otis, who died Jan. 17 at 90, Â are rightly recognized as innovators and icons of American rhythm ‘n’ blues and soul. But the jazz world — listeners, broadcasters and journalists, musicians and institutions up to and including the NEA — would be well-served […]

Who should the next NEA Jazz Masters be?

Who should be the next NEA Jazz Masters? With last night’s triumphant and deeply moving webcast of the NEA’s 2012 Jazz Masters induction ceremonies came welcome news the annual fellowships for these major American artists will continue — at least the financial awards of $25,000 per Master. More significant to many jazzers than the $ […]

NEA Jazz Masters @ Jazz at Lincoln Center live and webcast smash

The glory of living American jazz musicians filled Jazz at Lincoln Center last night to celebrate the 30th annual National Endowment of the Arts Jazz Masters fellowships — and some of the best news was the vitality of the music they played (webcast audio by WBGO and Sirius Radio, video at arts.gov). But of equally significance immediately […]

NEA Jazz Masters concert webcast, program to continue

The National Endowment of the Arts, formally inducting its 30th class of  “Jazz Masters” with a concert at Jazz at Lincoln Center January 10 2012 that is being webcast live on WBGO Jazz 88.3FM and SiriusXM Satellite Radio’s Real Jazz Channel XM67, (starting at 7:30 pm ET) has announced that Jazz Masters will again be named and receive […]

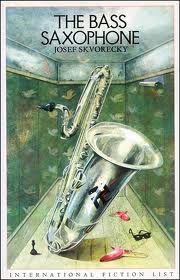

Josef Skvorecky, novelist of jazz = freedom & creativity, RIP

Josef Skvorecky’s The Bass Saxophone is one of a handful of fine novels identifying the extraordinary powers of jazz as an art form, a process, a heritage — which makes it more than something to listen or dance to. Several obits for the Czech writer (d. Jan 3, age 87) who was long exiled in […]

Arts presenters – jazzers, journalists included – kick of ’12 in NYC

The New Year starts bang! with performing arts presenters, artists and the journalists who cover them convening —  GlobalFest world music and  Winter Jazzfest musicians’ showcases — the NEA Jazz Masters fête  and shortly thereafter the  Chamber Music America conference, all in NYC. As pres of the Jazz Journalists Association, I’m happy to announce a four-session mini-conference on Media for Audience Development […]