Based on last week’s discussion of Hairspray on the podcast and on Arts Journal, and looking forward to the string of really exciting podcast guests I have coming up (!!), I realized I had a very specific thing I had been wanting to write about for months — or rather for years, since I first saw the show on Broadway in 2002. In fact, though this thing is so small and so specific, I felt it needed an entire “Theatre Love Letter” devoted to it. So without further ado…let me wax poetic about…Tracy Turnblad’s vertical bed in the opening number of Hairspray (“Good Morning Baltimore”).

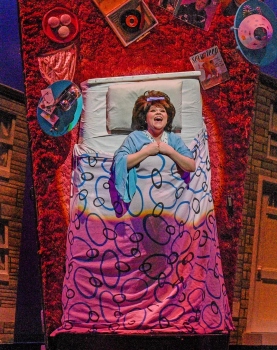

Maybe you saw the original Hairspray on Broadway (which I bet many of you did — it ran for nearly seven years and 2,642 performances). Maybe you saw one of the many National Tours that have since traveled the country (in fact, there’s a non-equity tour performing now, making its way to Ames, Iowa and La Crosse, Wisconsin this weekend). Maybe you saw the show when it opened on the West End in 2007, or on one of its many UK/Ireland tours. Or maybe you watched the Live! production on NBC in 2016, directed by Kenny Leon. (You couldn’t have remembered it, however, from either the original, 1988 John Waters source material or the 2007 film version, because neither of them open in this way). No matter what, if you’re anything like me the opening is seared into your brain: the lights fade down (on an overture version of what you’ll come to recognize as “I Can Hear the Bells”), and, in the dark you start to hear the classic syncopation of the drums. Bum….babum…BUM. Then, the lights pop up, and you see her — Tracy Turnblad — “asleep” in her teenage bedroom. But it’s not just any bedroom set, we can see Tracy’s “bed” is facing us vertically, as if we, the audience, have a bird’s eye view on her bedroom ceiling. An alarm clock rings, and Tracy “wakes up,” delivering the entire first verse and chorus of the song — “uh uh oooh woke up today/feeling the way I always do” — tucked “in bed,” before she flings her “sheets” off, splits the “bed” apart, and jumps into the rest of her day fully clothed — and from a normal vantage point.

I’ve seen a lot of Broadway musicals in my life (as I’m sure you can imagine). And I’ve loved a lot of moments. But nothing has stayed with me as much as this very specific aesthetic choice and the one minute and thirty seconds of pure magic it creates.

Now you may be wondering…Katie, this sounds like a cool moment, and, yeah, I remember it, but what makes it so special? Moreover, why devote an entire article to it? Well, first of all, I imagine many of my readers and listeners are just as big musical theatre nerds as I am, and want to focus on the specifics of our craft. And, second, I focus on it because, over the years of thinking about this particular set piece, and in advance of writing this article, I’ve come to see it as a symbol of musical theatre as a genre, and what makes it so special.

As discussed above, and as you may recall (if not — do yourself a favor and watch a clip on YouTube…I won’t fully condone bootlegs by linking you…but I’ll just say that it’s possible to find), the “vertical bed” I praise is a trick of set design — almost like a special effect — that makes the audience feel as if they are looking down at Tracy on her bed. It’s a strong perspective shift from that which the audience usually enjoys. In fact, one of the reasons many directors, and viewers, prefer film and TV to theatre is because of the ability to shift perspectives often: the camera can take the audience anywhere it likes. If you were watching the film version of Hairspray, for example, you wouldn’t be surprised if the movie opened with a perspective where you were looking down at Tracy on her bed (with the camera on the ceiling) and then immediately cut to looking straight at her, as if you were having a conversation. Obviously, over the years, filmmakers have been able to do far more than just switch camera angles, but that agility — the ability to take the audience anywhere, anytime, from any vantage point, as if you were truly a “fly on the wall,” or an unseen character in the story — is one of the things people love about film and TV, and which distinguishes it from other art forms.

Indeed, one of the critiques that people sometimes level at theatre is that there’s not much room to play with perspective or the audience relationship. Traditionally, the audience is looking up, or straight at, the onstage action, and their perspective doesn’t change much. What’s more, this proscenium relationship is expected — most audiences understand from years of theatregoing and years of theatre production in the world, from the days of the Greeks to A Beautiful Noise, that they will sit in their spots, looking directly at actors and dancers as they move roughly in front of, or slightly above, them. Even in the case of theatre in the round, a flexible, blackbox space, or, my worst nightmare, audience interaction, the perspective is pretty straightforward. Tracy’s vertical bed at the opening of Hairspray, however, acts like a film camera, shifting the traditional audience perspective, and audience relationship, and taking them up to the “ceiling,” looking “down” at our protagonist.

But this article is not one of those “anything film can do, theatre can do” think pieces. In fact, I’ll be the first to admit that Tracy’s vertical bed, though it shifts the audience perspective, does not deliver the same sense of realism that a camera can. Indeed, the Hairspray Live! opening is an especially interesting case study because it almost literally replicated the Broadway opening — the audience appeared to look down at Tracy using a vertical bed that could split apart. But because it was filmed with a camera, the moment felt more realistic. Even though it was being performed live, like a show, the camera made it believable that we, the audience, would look down at Tracy from her ceiling. When watching the show in a theater, you have the sensation that you’re looking down at Tracy while also knowing that you are in a proscenium-style theater, looking up at a stage in the audience.

In this way, Tracy’s vertical bed highlights the sense of doubleness inherent to a theatrical performance. You’re in their world, but you’re also still in the theater. The characters are the characters, but they’re also still themselves. It’s something people know about film — that the actors onscreen are separate people with separate lives, who were paid many months, if not years ago, to “act out” this story — but it’s easier to forget when the camera allows you, as the audience, to jump around so much and get so close up. Live theatre has to live in that duality for better or for worse — the sweat on a dancer’s face after finishing a tap number, the spike marks you can see from the mezzanine, the actor who forgets their lines or falls down.

Many performance studies scholars have written about this unique phenomenon: Alice Rayner’s 2006 book Ghosts: Death’s Double and the Phenomena of Theatre focuses on the ways that everything and everyone involved in a theatrical production becomes invariably “doubled” and therefore “haunted.” “Theatre, as a space of repetitions (with a difference),” Jennifer Cayer, another theatrical scholar says, “invites the doubling and blurring of a single given present.” Just as the actors appear as both themselves and their imagined characters, so the audience, Cayer argues, “by showing up for the 8:00 PM curtain…agrees to participate in a dream of sorts that is not altogether separate from their own daily lives.” As audience members we are ourselves — perhaps more so than the actors are themselves — but, building on the works of Lacan, Freud, Garber, and Ricoeur, Rayner would argue that they’re also something else, transformed by the theatrical performance, and their own participation in it.

And that’s the last amazing thing about Tracy’s vertical bed in Hairspray. Instead of trying to shy away from, or apologize for, the ways that it’s not realistic like film, it seems to acknowledge, with a kind of wink, its own fallacy, or, as Rayner would put it, its own “ghosts.”

It’s something I’ve long believed that musicals, in particular, do well. By already operating in a more “unrealistic” world, in which people break out into song and dance, musical theatre, more than any other form of performance, acknowledges, and accentuates, this doubleness. I think it’s why musicals are so often described as “meta” or are thought to have “wink to the audience” moments (I think about “like a professional” or “don’t help me” in The Producers, “well, wouldn’t you?” in Guys and Dolls, or “you’re all great dancers” in the most recent musical I saw, Some Like It Hot). As the ultimate form of artifice, to some extent uninterested in realism, musicals are able to reach new heights of expression. In this way, Tracy’s vertical bed in Hairspray becomes more than a trick of the eye and a shift in perspective, but a loud and proud acknowledgment of the artifice and joy of performance. “Welcome to Hairspray,” it seems to say. “We’re about to tell you a story.”

True Call Time fans may remember that when I had the honor of speaking with Jack O’Brien, the original director of Hairspray, on an earlier episode, I asked him about this moment and the vertical bed choice. While acknowledging that Hairspray was in no way the first show to use these kinds of aesthetics, he gave all credit to the scenic designer, David Rockwell, for whom Hairspray was only his second Broadway show. All of this demonstrates the power that one very short, but specific theatrical moment can hold. Indeed, for me, Tracy’s vertical bed stands for the ingenuity and creativity of theatrical designers, the fun and humor of a show like Hairspray, and the philosophical bedrock of musical theatre as performance (and ghost story?). I always knew I’d be talking about Hairspray and Lacan in the same breath…

Thanks for reading what was essentially a peek inside my brain this week. And please let me know in the comments: what did you think of this moment in Hairspray? Do you love it? Are there other, deeply specific moments in musical theatre to which you often return?

Love this. There’s nothing better than when a writer can take what might be looked over as simply fun and illuminate a broader, deeper idea. Thank you, Katie!

Another brilliantly written essay, illuminating a scene that I certainly took at face value, but is so much more interesting than just another set design! I love learning with you every week!