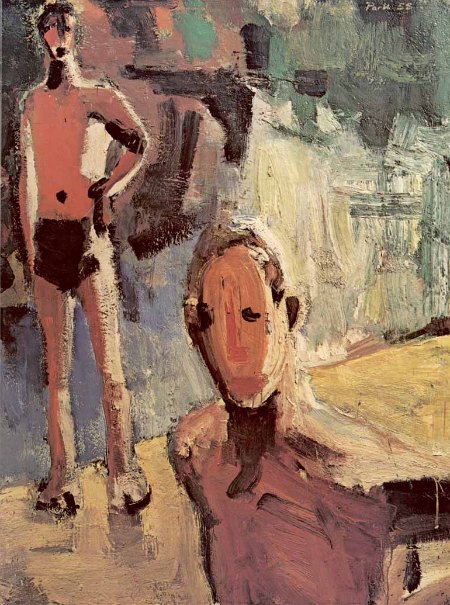

In 1949, David Park took his paintings to the dump. They were abstract in an Abstract Expressionist vein. With a clean slate, he used what he knew about the push and pull of moving paint around to return to the figure. Made of big, blunt brush-and-knife strokes, his quiet moments marked the beginning of Bay Area Figurative. In 1960, at age 49, he died of cancer.

Almost everyone I know who cares about art and lived in the Bay Area in the second half of the 20th Century considers his work a touchstone.

David Park (Image via)

In the 21st Century, his influence is everywhere, or, as Auden wrote about Yeats, “he has become his admirers.”

In the 21st Century, his influence is everywhere, or, as Auden wrote about Yeats, “he has become his admirers.”

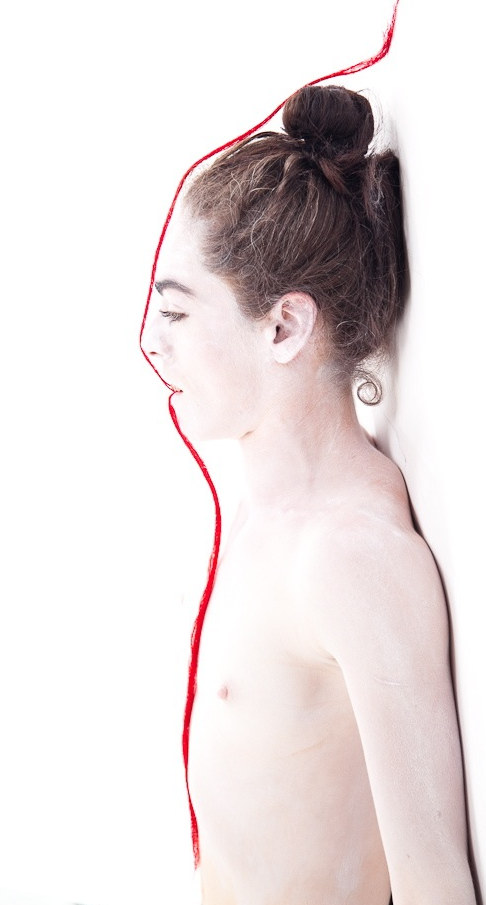

Julia Kuhl, for that quality of living in inside a head and stuck at an impasse, for the inadvertent tenderness.

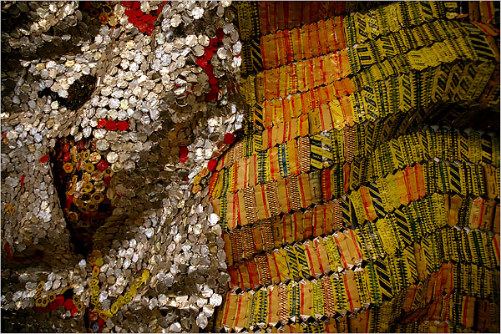

Peter F. Gross, for tactile intensity. (Anonymous Russian poet: “Can I help it if your bones rattle in my heavy, tender paws?”)

Peter F. Gross, for tactile intensity. (Anonymous Russian poet: “Can I help it if your bones rattle in my heavy, tender paws?”)

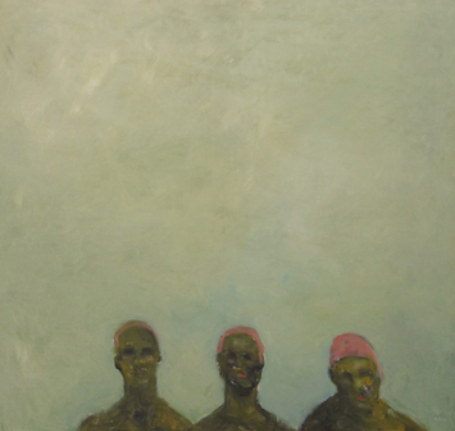

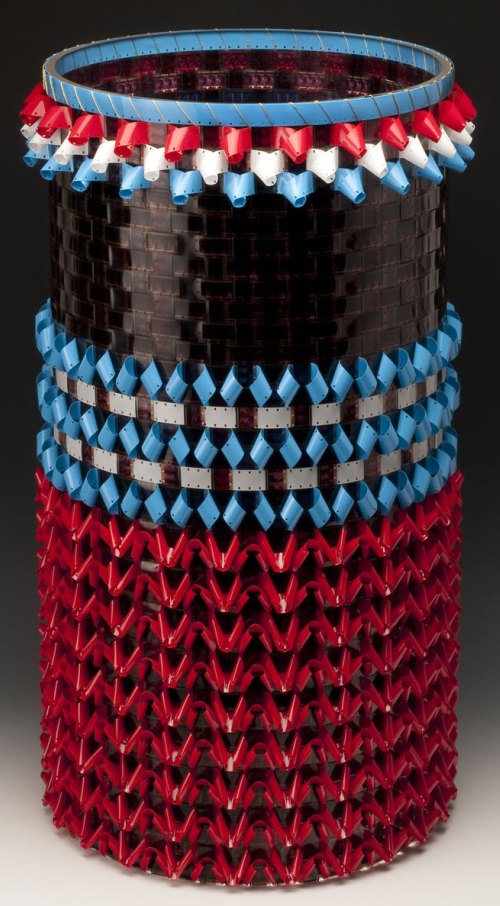

Mark Takamichi Miller – for bodies that own the air around them, without noticing it, and for big color.

Mark Takamichi Miller – for bodies that own the air around them, without noticing it, and for big color.

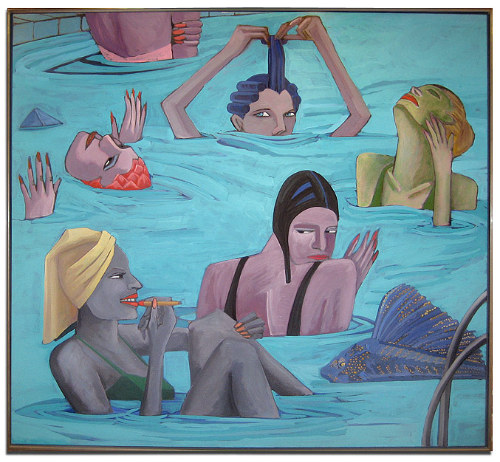

Mette Tommerup – What is the opposite of observant? A David Park figure.

Mette Tommerup – What is the opposite of observant? A David Park figure.

Brian Burke – stones in the river, lumpen proletariat in the sky.

Brian Burke – stones in the river, lumpen proletariat in the sky.

A happy hum

A happy hum And choreographed symbology, life in death.

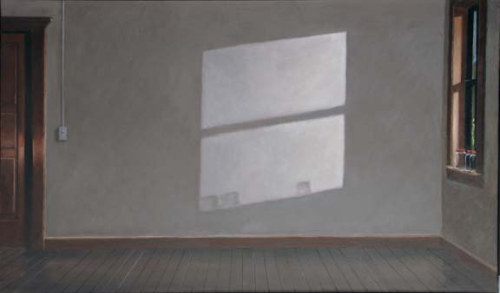

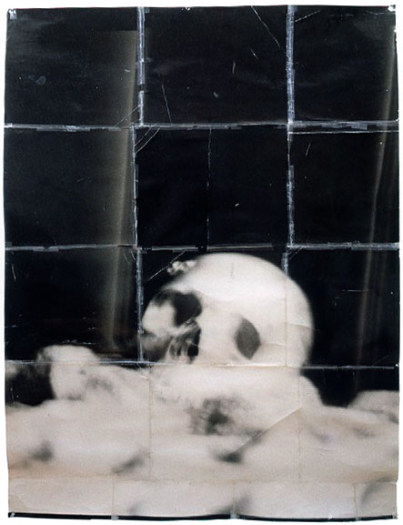

And choreographed symbology, life in death. About the artist’s own life I know little, but his paintings live in the world as depressed solitaries. The he who is their unseen narrator drives alone on country roads. Usually it’s raining. If he stepped outside, his shoes would sink into muck. If there’s light ahead, he hasn’t reached it.

About the artist’s own life I know little, but his paintings live in the world as depressed solitaries. The he who is their unseen narrator drives alone on country roads. Usually it’s raining. If he stepped outside, his shoes would sink into muck. If there’s light ahead, he hasn’t reached it. In describing his studio, the narrator allows himself a few flourishes. Like the Dutch before him, he can paint a bowl with the qualities of ceramic next to translucent glass and the dull sheen of polished tin. As a view beyond his leaded-glass windows, he can articulate spindly winter trees in a foggy purple haze.

In describing his studio, the narrator allows himself a few flourishes. Like the Dutch before him, he can paint a bowl with the qualities of ceramic next to translucent glass and the dull sheen of polished tin. As a view beyond his leaded-glass windows, he can articulate spindly winter trees in a foggy purple haze.  The play of light interests the narrator more than what it plays upon. Light is never redemptive, but it’s worth the time it takes to notice its qualities. Objects are interchangeable, like roads or tables or nude women reclining on beds.

The play of light interests the narrator more than what it plays upon. Light is never redemptive, but it’s worth the time it takes to notice its qualities. Objects are interchangeable, like roads or tables or nude women reclining on beds.  Here’s the entirety of Lundin’s artist statement:

Here’s the entirety of Lundin’s artist statement: Nearly 30 years later,

Nearly 30 years later,

It’s the meaning of their movements,Salander in a boxing ring, Scofield on stage. Scofield never would have made it as a ballet dancer, she says in the video below, because she “couldn’t stay in line.” Any line other than her own. She is light on her feet but owns the floor. Gravity

It’s the meaning of their movements,Salander in a boxing ring, Scofield on stage. Scofield never would have made it as a ballet dancer, she says in the video below, because she “couldn’t stay in line.” Any line other than her own. She is light on her feet but owns the floor. Gravity At the

At the  To his interest in what it means to live in a body, Shuey contributes a haunted unease, an inability to connect. The gap between him and other people equals the gap between him and himself. He involves the audience in his perceptual play, shrouding visitors in doubt the way fog rolls over the moors when Sherlock Holmes walks on them.

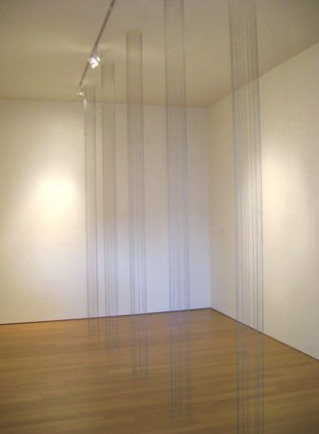

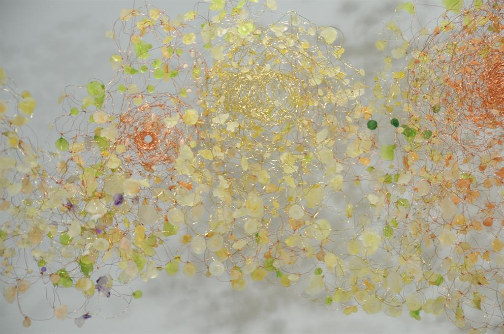

To his interest in what it means to live in a body, Shuey contributes a haunted unease, an inability to connect. The gap between him and other people equals the gap between him and himself. He involves the audience in his perceptual play, shrouding visitors in doubt the way fog rolls over the moors when Sherlock Holmes walks on them. More than 2,000 strands make an overhead cove in the gallery space. Each one is a vertical drawing, a dissolute calligraphy lost in the chorus of its fellows.

More than 2,000 strands make an overhead cove in the gallery space. Each one is a vertical drawing, a dissolute calligraphy lost in the chorus of its fellows.

Hickey, Seattle 1997

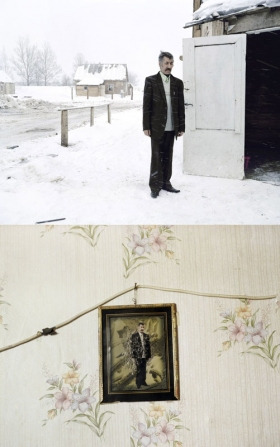

Hickey, Seattle 1997 In 2007, he published a book of portraits featuring Lithuanian Roma titled,

In 2007, he published a book of portraits featuring Lithuanian Roma titled,  Miksys:

Miksys: