Norman Lundin is slow to embrace the new. He stakes his studio practice in the pre-modernist 19th century, as an off-shoot of the Barbizon School with a hat tip to 17th Century Dutch still life. His palette is sliver-gray and mossy green. When he hits a hot note, it’s usually an emergency, like a fire.

The Fire at Petersons Crossing

oil / canvas, 2008

unframed: 38 x 86″

About the artist’s own life I know little, but his paintings live in the world as depressed solitaries. The he who is their unseen narrator drives alone on country roads. Usually it’s raining. If he stepped outside, his shoes would sink into muck. If there’s light ahead, he hasn’t reached it.

About the artist’s own life I know little, but his paintings live in the world as depressed solitaries. The he who is their unseen narrator drives alone on country roads. Usually it’s raining. If he stepped outside, his shoes would sink into muck. If there’s light ahead, he hasn’t reached it.

Tornado Weather Northeastern Wyoming oil / canvas, 2010

42 x 90″

In describing his studio, the narrator allows himself a few flourishes. Like the Dutch before him, he can paint a bowl with the qualities of ceramic next to translucent glass and the dull sheen of polished tin. As a view beyond his leaded-glass windows, he can articulate spindly winter trees in a foggy purple haze.

In describing his studio, the narrator allows himself a few flourishes. Like the Dutch before him, he can paint a bowl with the qualities of ceramic next to translucent glass and the dull sheen of polished tin. As a view beyond his leaded-glass windows, he can articulate spindly winter trees in a foggy purple haze.

Studio in Half Light II

oil / canvas, 2009

31 x 91″

The play of light interests the narrator more than what it plays upon. Light is never redemptive, but it’s worth the time it takes to notice its qualities. Objects are interchangeable, like roads or tables or nude women reclining on beds.

The play of light interests the narrator more than what it plays upon. Light is never redemptive, but it’s worth the time it takes to notice its qualities. Objects are interchangeable, like roads or tables or nude women reclining on beds.

Room with Three Jars oil / canvas, 2010

40″ x 66

Here’s the entirety of Lundin’s artist statement:

Here’s the entirety of Lundin’s artist statement:

The less you have, the more important what is there becomes.

Nearly 30 years later,

Nearly 30 years later,

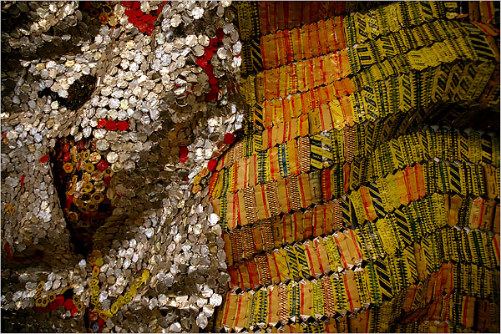

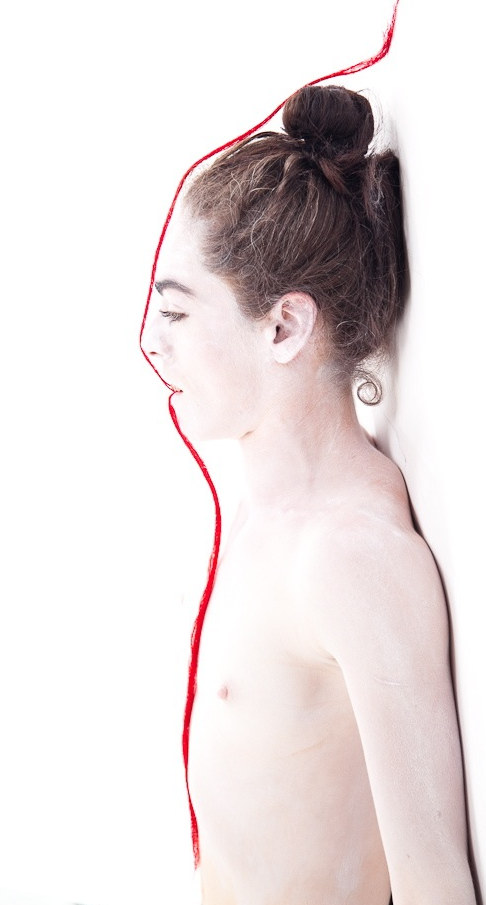

It’s the meaning of their movements,Salander in a boxing ring, Scofield on stage. Scofield never would have made it as a ballet dancer, she says in the video below, because she “couldn’t stay in line.” Any line other than her own. She is light on her feet but owns the floor. Gravity

It’s the meaning of their movements,Salander in a boxing ring, Scofield on stage. Scofield never would have made it as a ballet dancer, she says in the video below, because she “couldn’t stay in line.” Any line other than her own. She is light on her feet but owns the floor. Gravity At the

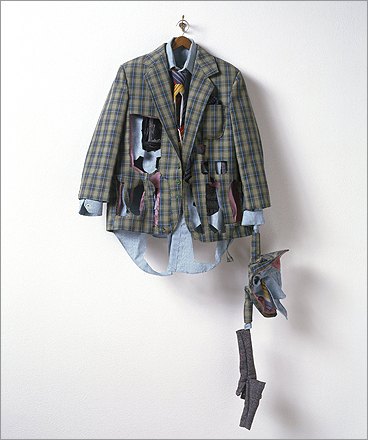

At the  To his interest in what it means to live in a body, Shuey contributes a haunted unease, an inability to connect. The gap between him and other people equals the gap between him and himself. He involves the audience in his perceptual play, shrouding visitors in doubt the way fog rolls over the moors when Sherlock Holmes walks on them.

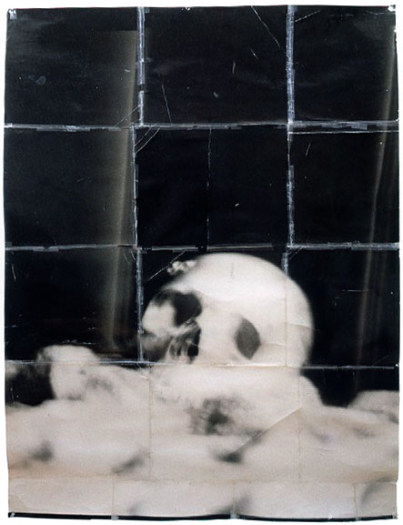

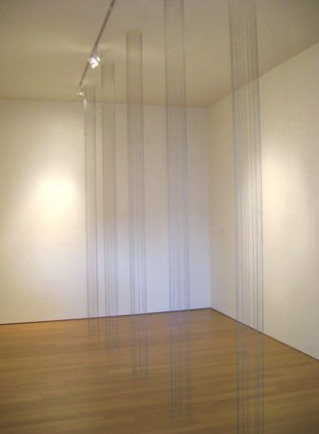

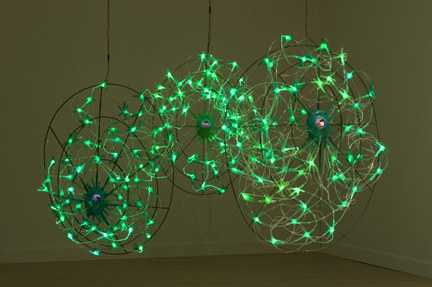

To his interest in what it means to live in a body, Shuey contributes a haunted unease, an inability to connect. The gap between him and other people equals the gap between him and himself. He involves the audience in his perceptual play, shrouding visitors in doubt the way fog rolls over the moors when Sherlock Holmes walks on them. More than 2,000 strands make an overhead cove in the gallery space. Each one is a vertical drawing, a dissolute calligraphy lost in the chorus of its fellows.

More than 2,000 strands make an overhead cove in the gallery space. Each one is a vertical drawing, a dissolute calligraphy lost in the chorus of its fellows.

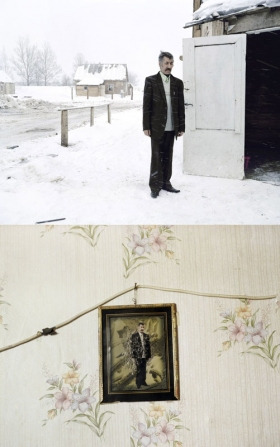

Hickey, Seattle 1997

Hickey, Seattle 1997 In 2007, he published a book of portraits featuring Lithuanian Roma titled,

In 2007, he published a book of portraits featuring Lithuanian Roma titled,  Miksys:

Miksys: