His trio came to my once-segregated Missouri hometown in 1969 to play a concert that made a lasting impression on me. Would that the film’s brief performance sequences offered more than a tantalizing taste of his playing! The Shirley I saw on stage a half-century ago was a man of polished urbanity whose private melancholy—he appears to have been a closeted gay—is depicted by Messrs. Ali and Farrelly with sharp, sad clarity.

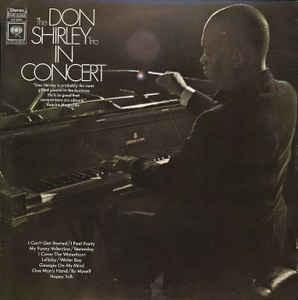

I recall that concert vividly, in part because it was the first time I ever saw a black musician perform in person. I was thirteen years old and had only just started listening closely and attentively to my father’s albums and 78s, many of which featured the likes of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Erroll Garner, and (my favorite) the King Cole Trio. Unlike them, Shirley wasn’t a true jazzman: he was a classically trained musician who took up popular music only after being warned by Sol Hurok, the Russian-American classical-music impresario, that a “colored man” couldn’t hope to make a living as a concert pianist in America. From then on, he played his own written-out arrangements of pop tunes and spirituals accompanied by a classical-style “rhythm section” of cello and double bass, and had considerable success doing so throughout the Fifties and Sixties. Nevertheless, Shirley was the closest thing to a jazzman that I’d seen in the flesh, and I was so impressed by him that I blew a week’s allowance on a copy of The Don Shirley Trio in Concert, then taught myself how to play by ear the bass part to his arrangement of “Water Boy.”

The “Don Shirley” of Green Book is in many ways very much like the man I saw on the stage of the Smalltown Middle School gymnasium, the same stage on which I saw my first play, a high-school production of Blithe Spirit, later that year. Surviving interview footage suggests that Shirley, unlike Ali, was more than a little bit campy, but I was too naïve in 1969 to know a gay man when I saw one. (Not until years later did I finally figure out that my best friend at the time was gay.) What struck me about him, rather, was his absolute self-assurance, a quality that Ali conveys with perfect fidelity.

Needless to say, I couldn’t possibly have known what it took for a black man—much less a gay black man—to stand up in front of a white audience in a small town located a stone’s throw from the Deep South and conduct himself with that kind of unflappable poise. Shirley hinted at what it took, though, when he spoke to a New York Times reporter in 1982:

I am not an entertainer. But I’m running the risk of being considered an entertainer by going into a nightclub because that’s what they have in there. I don’t want anybody to know me well enough to slap me on the back and say, “Hey, baby.” The black experience through music, with a sense of dignity, that’s all I have ever tried to do.

These, however, are reflections very much after the fact. At the time, I knew only that the elegant man seated at the piano was one of the most fabulously gifted musicians I’d ever heard, and listening to him made me think that I might possibly want to become a professional musician, too.

I did, at least for a time, but I never saw Don Shirley play again, and when I read about Green Book last fall, it was the first time I’d thought of him in years. I wish our paths had crossed in later life: I would have liked to tell him what it meant for me to see him perform in Smalltown in 1969. Perhaps it would have pleased him, for he died in semi-obscurity, his great talent all but forgotten.

It is for this reason that I have no trouble forgiving the failings, such as they are, of Green Book. Everyone who watches it, after all, comes away knowing exactly who Don Shirley was, and what he did. I can’t see anything bad about that.

* * *

Don Shirley’s 2013 New York Times obituary is here.A rare film clip of Don Shirley playing Richard Rodgers’ “Happy Talk” in concert, accompanied by Robert Field on bass:

The Don Shirley Trio plays Shirley’s arrangement of “Water Boy” at Carnegie Hall in 1968. Gilberto Mungula is the cellist, Henry Gonzalez the bassist: