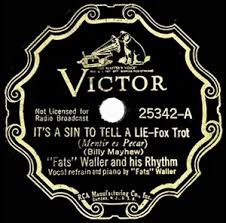

Fats Waller, after Louis Armstrong the most life-enhancing jazz musician ever to make recordings, is never very far from my iTunes player. Needing a pre-bedtime boost of spirits, I clicked on “It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie,” one of his celebrated deconstructions of insipid Thirties pop tunes, and began smiling from the first bar onward. It starts with a get-the-hell-out-of-my-way introduction, immediately succeeded by a jaunty chorus of solo piano in which Waller’s infallible left hand bounces up and down the keys like a fat man on a pogo stick.

There follows a quintessentially Wallerian vocal that goes something like this, sort of:

Be sure it’s true when you say “I love you.”

It’s a sin to tell a lie-uhhllllrrrry!

[unctuously] Millions of hearts have been broken, yes, yes,

Just because these words were spoken. (You know the words that were spoken? Here it is.)

[simperingly] I love you I love you I love you [in an orotund bass-baritone] I love you. [gleefully] Ha-ha-ha!

Yes, but if you break my heart, I’ll break your jaw and then I’ll die.

So be sure it’s true when you say “I love [twitteringly, in falsetto] yooooou.” Ha, ha!

It’s a sin to tell a lie. Now get on out there and tell your lie. What is it?

But words fail me. Go here and rejoice in the real right thing.