Nearly two months ago, the Brooklyn Museum’s* press office sent me links to two blog posts about its Russian paintings, saying I might be interested. I was, but not until now, as you will see shortly.

The first was about an exhibit of the museum’s modern Russian paintings collection, acquired starting in 1906. Russian Modern, “celebrates for the first time in over eighty years its renowned collection of modern Russian paintings,” wrote Richard Aste, Brooklyn’s curator of European paintings. Which makes one wonder why such a renowned collection hasn’t been on view for so long, right?

The first was about an exhibit of the museum’s modern Russian paintings collection, acquired starting in 1906. Russian Modern, “celebrates for the first time in over eighty years its renowned collection of modern Russian paintings,” wrote Richard Aste, Brooklyn’s curator of European paintings. Which makes one wonder why such a renowned collection hasn’t been on view for so long, right?

In the second post, Aste talks about refining the collection by deaccessioning one of three paintings by Vasily Vereshchagin called Crucifixion by the Romans, from 1887 (above). Explaining his decision to dump it, he wrote:

Crucifixion by the Romans is a wonderful example of Vereshchagin’s passion for late 19th-century European academic painting. Theatrically staged in 1st-century A.D. Jerusalem, the picture is typical of the dramatic historical spectacles–here of capital punishment under the Roman Empire–that wowed period audiences across Europe and America. Today the painting continues to impress the viewer with its monumentality and academic exoticism or Orientalism… [and] an awesome sense of realism.

Crucifixion is not, however, an example of Russian avant-garde painting–the focus of Brooklyn’s collection– which in Vereshchagin’s own lifetime meant critical depictions of modern Russian society or Critical Realism….[it is] a powerful expression of Vereshchagin’s foray into Orientalism, and as such it merits greater study and exposure than it could get here, where it was last on view in 1932.

There’s more at the link above. ArtDaily also published an article with information about the painting’s reception and exhibition history.

Brooklyn invited comments, and got them: of six (plus a final note from Aste), four came from experts opposing the sale for good reasons; one came from an unknown agreeing with them. A sixth — also from an unknown — said “The truth is the crucifixion is in terrible condition, and couldn’t be shown without heavy work, which the museum couldn’t afford on the spot.”

Brooklyn invited comments, and got them: of six (plus a final note from Aste), four came from experts opposing the sale for good reasons; one came from an unknown agreeing with them. A sixth — also from an unknown — said “The truth is the crucifixion is in terrible condition, and couldn’t be shown without heavy work, which the museum couldn’t afford on the spot.”

Aste responded by repeating his earlier points and concluded, “The Brooklyn Museum is neither physically nor curatorially positioned to properly celebrate this painting; it hasn’t been [sic] since 1932 and it will not be in the foreseeable future.”

But wait — the others haven’t been on view since 1932 either, have they? Why not is another pertinent question. And, if, as he wrote, the painting deserves greater study, how could that be accomplished by selling it, most likely, to a private collector?

Meanwhile, Christie’s, calling the work “incredible,” put the painting in its London sale of Russian art, which took place on Monday. Estimated at £1,000,000 – £1,500,000

($1,545,000 – $2,317,500), the work fetched £1,721,250 ($2,664,495), including the buyer’s premium.

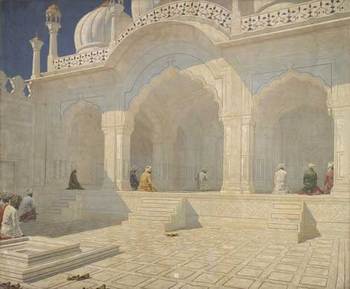

Vereshchagin is having a bad, or good, depending on how you look at this, month. In early November, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, also deaccessioned a painting by him — Pearl Mosque at Delhi fetched $3.1 million, including the premium, vs. an estimate of $3 million to $5 million. MFA had a bit of an excuse — at 13 ft by 16 ft, it had little room to show it and it was rarely on view. The proceeds will help the MFA purchase Caillebotte’s Man at His Bath.

At least there we know where the money will go. What will Brooklyn do with its new funds? I have no doubt that they will be used to buy art, but what kind? Will the funds stay in the European painting department, as they should? The museum hasn’t said.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of Christie’s (top); Sotheby’s (bottom)

*I consult to a foundation that supports the BM

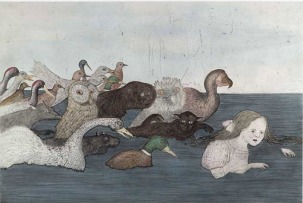

The exhibition goes to the source: Carroll’s original 1864 manuscript, which he wrote and illustrated as a gift for ten-year-old Alice Liddell; it’s on loan from the British Library. The images were, as the Tate says, “central to the story, creating a visual world which took on a life of its own.” Carroll’s drawings and photographs, as well as Victorian Alice memorabilia (biscuit tins, tea tins, figurines, etc.) and John Tenniel’s preliminary drawings for the first edition of the novel, are on view.

The exhibition goes to the source: Carroll’s original 1864 manuscript, which he wrote and illustrated as a gift for ten-year-old Alice Liddell; it’s on loan from the British Library. The images were, as the Tate says, “central to the story, creating a visual world which took on a life of its own.” Carroll’s drawings and photographs, as well as Victorian Alice memorabilia (biscuit tins, tea tins, figurines, etc.) and John Tenniel’s preliminary drawings for the first edition of the novel, are on view.  Levkoff, since 2009 the curator of sculpture and decorative arts at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, wrote the book while she was curator of European sculpture and classical antiquities at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; LACMA present a show with the same title in 2008-09.

Levkoff, since 2009 the curator of sculpture and decorative arts at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, wrote the book while she was curator of European sculpture and classical antiquities at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; LACMA present a show with the same title in 2008-09. When I last wrote about the Center

When I last wrote about the Center  That’s when the trouble began. According to a press release,

That’s when the trouble began. According to a press release,