main: May 2007 Archives

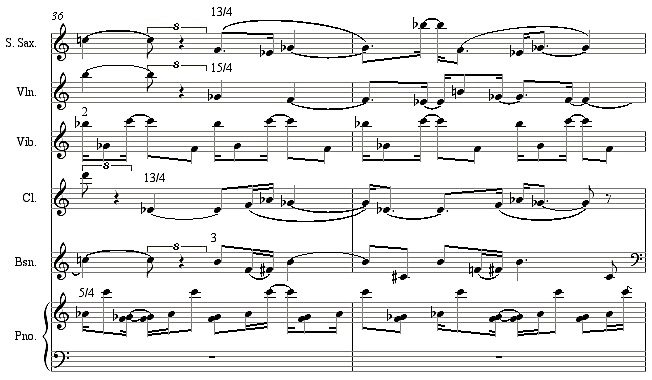

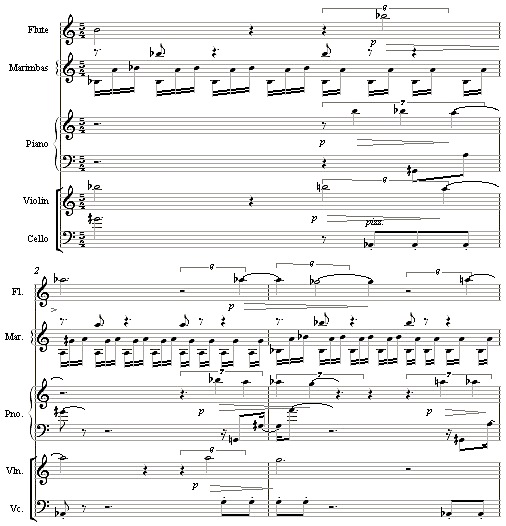

I spoke in my last post of James Tenney's postminimalist streak, which I have always most associated with his Tableaux Vivants of 1990. A few years ago, learning of my intense interest in the piece, Jim kindly sent me a score, and I've long itched to analyze it, never finding the time until this week. As I start working my way through it, I realize that it is far more complex than it sounds on the recording by the Toronto ensemble Sound Pressure, and that it is really not postminimalist at all, but rather classically totalist, or, as we now call it here, metametric. It is unusual for Tenney in being composed mostly of repeated phrases, and in that those phrases loop at different lengths to create a counterpoint of recurring impulses at different speeds (or rather a "harmony of phrase lengths," as Cowell would have said). The piece sounds gently undulating, not as wild as it looks, because of its uniformly soft dynamic level. May Doug McLennan and those with dial-up modems forgive me, but I'm going to post several measures of this 20-minute work here. All I've added, in numbers above each new phrase, is the length of the phrase expressed in beats (i.e., 11/3 = 11/3 of a quarter-note long, or 3 and 2/3 beats):

As you can see, or figure out anyway:

the first "moment" in mm. 34-35 forms lines in triplet 8th-notes, to make repeating periodicities of 5 against 7 against 11;

mm. 36-37 move to a 16th-note common unit for phrase/phase relationships of 5 against 12 against 13 against 15 (12 being the clarinet line three beats long);

m. 38 changes back to triplets for loops of 3 (piano) against 8 (violin) against 9 (clarinet) against 13 (bassoon) against 16 (sax);

and in mm. 40-42, a trio pursues phrase loops of 15 against 17 against 25 in 16th-notes. Notice that this last passage is entirely within the B-flat major scale.

I've posted Sound Pressure's recording of the piece here. The excerpt given above begins at 2:18, immediately following the first sustained vibe-and-piano chord.

In his program notes, Jim calls the piece an attempt "to resume the exploration of harmony in the twentieth century without regressing to some earlier style...." He alludes to stochastic processes, by which I imagine he means the way the pitches are chosen, which seems somewhat random from "moment" to "moment": the instruments overlap in pitch considerably (which puts the bassoon, you'll notice, in an incredibly high register even above Le Sacre du Printemps), and the harmonies range from quite tonal to sharply dissonant. I take this to mean that the harmonic aspect of the piece is not susceptible to conventional analysis; if anyone knows more about the piece in this (or any other) respect, I'd appreciate some sharing of information.

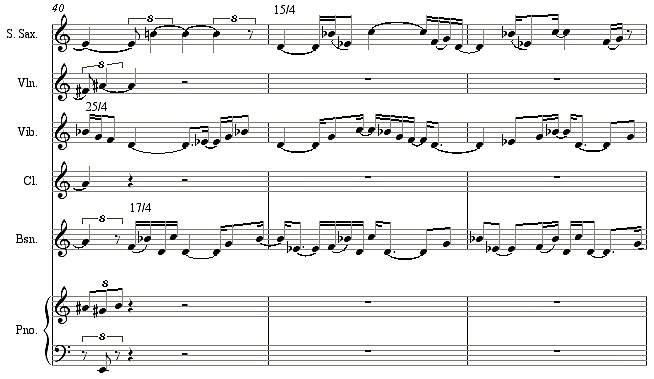

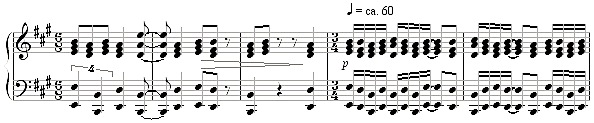

What surprises me most is the use of repeated motives in lengths not divisible by the quarter-note beat to create an effect of conflicting periodicities not based on the beat, and also a kind of gear-shifting effect, as those periodicities switch among lengths like 13/3, 3, and 15/4, quite akin to what totalists like Michael Gordon, Mikel Rouse, and myself were doing in the '80s and '90s. Compare it, for instance to this gear-shifting effect, also using "misaccented" triplets to change the perceived pulse, from my Snake Dance No. 2 (1994) for unpitched percussion:

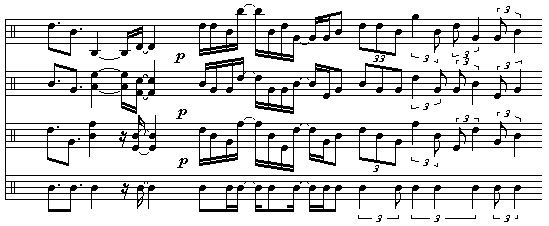

Then with this passage from my Unquiet Night (2004) for Disklavier, which combines periodicities of 21/13 of a measure (top system), 16/11 of a measure, and 13/7 of a measure:

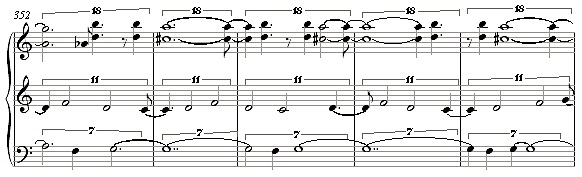

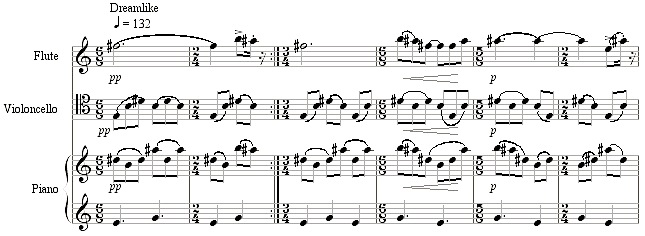

Then look at this passage near the end of Bunita Marcus's chromatically saturated Adam and Eve (1987), with its implied periodicities slightly longer than a measure in the piano, violin, and flute, and an impression of layered tempos created by both triplets and septuplets:

It so happens I still have Adam and Eve on my web site, so you can hear it here; the excerpt above comes late in the piece.

Next here's an excerpt from Michael Gordon's Yo Shakespeare (1993 - mp3 on my web site here). The little threes above the top system indicate triplet quarter notes, even though other notes are interpolated between them; the grouping of triplets in quantities indivisible by three was a potential Henry Cowell pointed to in New Musical Resources, which I also tried out in my Folk Dance for Henry Cowell (1997). I don't even know what instruments these are in Michael's score, because my old copy was pre-publication, but each line is doubled. The top system gives a repeating rhythm 7/3 beats long in quarter notes, the middle line has a rhythmic pattern 7 16th-notes long (7/4 of a beat), and the bottom repeating phrase is five beats long:

And we can even find the same basic idea in easier, more orchestrally digestible form in John Adams's Lollapalooza (1995), one of his most totalist works. Here a three-beat ostinato in the bass clarinet marks a steady tempo against which the other instruments repeat ornamental phrases at various periodicities, including the title "Lollapalooza" motive every five beats in the triombones and tuba (score greatly simplified and much material omitted):

I'd like to think that Adams was inspired to play with loops-out-of-phase by listening to the younger generation, but he could well have absorbed the same technique from Nancarrow, whose music he has championed, and whose Studies Nos. 3, 5, and 9 in particular experiment with a similar device. Another example could be John Luther Adams's Dream in White on White (1992), which carries out the idea at lengths too great to quote in notation here. Even I've got limits.

In any case, I was pleasantly surprised to find Tenney playing around with the same metametric concerns as me and my totalist crowd. Any info about Tableaux Vivants would be much appreciated. Perhaps he even has other similar pieces, I'm certainly not familiar with his entire output. The examples above will be raw material not only for my Music After Minimalism book, but for a paper I'm presenting ("Phase-Shifting as an American Compositional Temptation") in September at a minimlism conference at the University of Bangor in Wales.

Someday someone will appear who has analyzed more minimalist-influenced music from the 1980s and '90s than I have, and if that person feels that I have divided my era into categories inappropriately, I will be glad to listen to her argument. So far, I've gotten plenty of argument, but only from people who don't come anywhere close to fitting that description.

There are several ways to characterize a style. One is to catalogue all relevant qualities associated with pieces associated with that style. I've done this for postminimalism elsewhere, and I have no intention of replicating that feat today. Another, less cautious tactic is to isolate a compositional aim that one perceives as the essence of a style. This has the disadvantage of marginalizing (or at least discategorizing) pieces that do not manifest that particular idea, for artistic styles, it seems to me, are rarely homogenous in their makeup. Nevertheless, if I had to point to one characteristic that strikes me as quintessential to postminimalism, it would be the impulse to write music freely and intuitively within a markedly circumscribed set of materials, outside of which the piece "knows in advance" it will not venture. For me, and reinforced by the contemporaneous writings of Steve Reich, minimalism's essence was its quasi-objectivity, its linear movement from one point to another, along with its adherence to audible process or structure. Postminimalism at once became much more subjective, often even mysterious, imitating minimalism's extreme limitation of resources but replacing the idea of linear, audible structure with that of a nuanced, intuitive musical language.

For instance: Several movements of Bill Duckworth's Time Curve Preludes (1978-79) fit this paradigm exactly. Not all of them, for Time Curve Preludes is something of a transitional work, and several movements preserve the idea of additive and subtractive process that I think of as continuing minimalist practice. Prelude No. 7 is a movement that strikes me as the postminimalist piece par excellence:

This languorous dance is made up of only three elements: a slowly arpeggiated bass line whose final dyad sometimes gets extended (A); a melody that here and there breaks the continuity (B); and a set of six chords that create an impression of bitonality by wandering conjunctly through scales from various keys, though the lower two lines are not actually diatonic (C):

There is some inheritance from minimalism here in the systematic way the phrase lengths expand at first according to lengths proportional to the Fibonacci series, but even this structural element recedes as the B melody intrudes more and more. You can listen to the movement here. I don't think of the Time Curve Preludes as Bill's best piece any more than I think of In C as Terry Riley's best piece, but they are parallel in that they seem to be their respective composers' most memorable pieces, the ones everyone knows, the ones whose perfectly clear intentions serve as a manifesto, of which their subsequent music works out the ramifications.

Even more restrictive in their materials are some of Peter Garland's works. Here is an excerpt, mm. 19-23 (showing a transition between sections) from the second movement of his piano piece Jornada del Muerto (1987):

The entire movement employs only five chords in the right hand - given only as seen here, mind you, with no transpositions or octave displacements - plus the pitches B, D, and E in the left hand, usually as octaves, and in one section as single notes:

No process or continuity device informs this music; it is entirely and intuitively melodic in conception, if chordal in execution. Yet despite its extreme paucity of material, this lovely five-minute movement goes through seven sections touching on four different textures and rhythmic styles, undulating between two tempos. "I feel influenced," Peter has said, "by American modernism from the '20s, not the '50s and '60s. My take on modernism goes back to Cowell and Rudhyar." Point taken: a line can be drawn from Garland's use of only specific sonorities to the (vastly underrated) piano music of Rudhyar. Nevertheless, the conscious asceticism of his music is a far cry from Rudhyar's employment of the entire piano as a mammoth sounding board, and it is worth noting that Peter studied at CalArts side by side with two other seminal postminimalists, Guy Klucevsek and John Luther Adams (all with Jim Tenney, who had his own postminimalist streak). In any case, the appearance of Jornada del Muerto in the late '80s was exactly in keeping with the then-current postminimalist aesthetic. You can hear the second movement here.

Like Duckworth's, Janice Giteck's music is widely heterogenous in its sources of inspiration, but each movement blends those sources into a seamless fusion. The fourth movement of her Om Shanti (1986) draws inspiration from Indonesian gamelan music, and its melody, sung wordlessly by the soprano and doubled in various other instruments, runs along a pelog scale, F G B C E:

The piece is pervaded by a single line of 8th-notes running without interruption through the piano left hand and clarinet, all on those five pitches E F G B C, without ever repeating, like an endlessly flowing river that is never the same twice. In addition, the pitch A appears in the voice melody and its doublings, but only in the upper register and at moments of maximum intensity. At various points the melody is punctuated, as shown above, by one or two notes in the upper piano and crotales, always on the ambiguously unresolving pitch F, rendered even more unsettling by a bass note B in the cello (whose C string gets tuned down to B in the third movement, but that's another story). The movement, which you can hear here, is a masterpiece of intuitive intensification of melody, texture, and even harmony within an invariant limited scale.

Merely five pitches also suffice for the nine-minute length and formal complexity of Paul Epstein's Palindrome Variations (1995): G A Bb C D. The most formalist of them all, and a purveyor of note-by-note intricacy, Epstein could be called the Webern or Babbitt of postminimalism, the extremist in search of a purely musical logic. His 1986 Musical Quarterly article "Pattern Structure and Process in Steve Reich's Piano Phase" gives almost more insight into his own composing impulses than it does into its ostensive topic; he is fascinated by note combinations that result from permutational patterns. All the same, Palindrome Variations is not (as some Epstein pieces are) a work composed by linear process. What's interesting about Epstein is that the musical units with which he works intuitively are not notes, chords, or even phrases, strictly speaking, but notational units resulting from the interplay of meter and repetition. Here, the 6-beat phrase of the first two measures (repeated in the second one) is rotated within the measure afterward, so that in m. 3 the pattern starts on the third beat, in m. 4 on the fourth, in m. 5 on the sixth, m. 2 on the second, and so on:

Of course, in so uniform a texture, the meter isn't felt as a unit, and so the effect is a constant unpredictable juggling of the same elements over and over. By a nonlinear process of note substitutions, the texture gradually transforms into a canon in which all instruments are playing the same motive but out of sync; then there are canonic solos for the flute and cello, and with inexplicable logic the piece moves to a conclusion foreshadowed by a dominant preparation and a convincingly logical, almost Bartokian, closing move to unison melody, all without any perceived breaks in Epstein's tightly wound motivic flow. You can hear all that here. I think of Epstein as music's answer to an op artist like Bridget Riley, whose superficially strict procedures result in wildly expressive visual surprises; similarly, Epstein's rigorous attention to geometric detail creates conundrums for the ear. I doubt anyone can deny that, like Babbitt within the 12-tone world, he sets a certain edge beyond which postminimalism can go no further.

The first 25 measures of Belinda Reynolds's Cover (1996) certainly seem to be those of a postminimalist piece. Again, only six pitches are used - E F# G A# B D# - with E in the piano as a low drone note, and a certain obsessive reiteration of characteristic figures, particularly the competing fifths E-B and D#-A# (repeat sign not in the original, but mm. 3 and 4 are identical to 1 and 2):

However, the music crescendoes to a sudden new chord at m. 26, and subsequently every few measures the music ups the energy by shifting to a new scale. There might be no reason to call this curvaceous, quasi-organic piece postminimalist except that, within each "moment" (to use the Stockhausenesque term), it tends to build up pitch sets and melodies additively, starting as an undulation of two notes and adding in others, almost like a memory of minimalism. Ultimately, Cover's form is not postminimalist - there are no more implied limitations on where the music could go than there are in Mozart - but its technique is. One of the advantages of defining postminimalism (or any style) in terms of its central idea is that we can treat the style itself as an ideal form, and talk about degrees to which a particular piece participates in that style. Just as Time Curve Preludes lies slightly on one side of postminimalism, coming from minimalism, Cover is a piece evolving from postminimalism and leaving it behind toward something else, but with its origins still much in evidence. You can hear the entire ten-minute work here.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Now, don't write in and tell me you don't like these pieces. Who cares if you like these pieces? Do I care if you like these pieces? Do I, Kyle Gann, personally give a shit whether you like these pieces? No. No, my friend. I do not. What I care about is that you acknowledge that these pieces by different composers with very different creative personalities share several very clear stylistic characteristics - that they, in effect, define a style. What we name that style, I do not care. If everyone wants to call it Charlie, we can call it Charlie. But I have called it postminimalism, because that word was already in use in the early '80s but floating around loose without any specific definition. (Rob Schwarz applied the word to John Adams and Meredith Monk in his Minimalists book of 1996. But I have trouble finding important differences in method between Meredith and the true minimalists, while composers of the "neoromanticism with minimalist elements" style that Adams represents were vastly outnumbered in the '80s by the postminimalists who fit my definition. There are many more of them today.) And it is clear that these composers were all reacting to minimalism, but that minimalism was not their only influence. They defined, among them, a soundworld quite different from minimalism, one of brevity rather than attention-challenging length and stasis, one of intuitive lyricism and mysticism rather than obvious structure and worship of "natural" processes.

Nor - to preclude the kind of silly clichés that some composers bring to these discussions - is postminimalism a "club" that anyone ever decided to join. Not one of these composers ever sat down and said, "I'm going to write a postminimalist piece," and it would be surprising if anyone (aside from myself) ever has. Anyone who thinks there could be a "doctrinaire" postminimalist doesn't understand. The style is accompanied by no ideology. Nor was postminimalism even a "scene." Duckworth and Giteck were unaware of each other until I introduced them. I doubt Peter Garland has crossed paths with Belinda Reynolds to this day. Minimalism unleashed a set, or several sets, of potentialities into the ether, and, in the way that great minds so often think alike, several dozen composers pulled new musical solutions out of the air that happened to have a lot in common. The grouping of these composers into a postminimalist style is not a fact of composition, but a fact of musicology. It is the perception of the first person to study all this music - and I have hundreds more examples where these came from, don't even get me started on my John Luther Adams file - that commonalities among a certain body of pieces constitute a style. That perception will stand (and has already been widely quoted in the literature) until it is replaced by a more compelling perception, as perhaps will happen someday. This remains true even despite the music world's refusal to deal with this music as a repertoire, after the vogue it enjoyed temporarily among the New Music America crowd in the mid-1980s.

I wonder if that indifference is perhaps due to postminimalism's generally formalist concerns, its fascination with pattern and texture, at a time when the music world had become totally disenchanted with formalism. The widespread abandonment of serialism around 1988 (the year it seemed to me that disgust with the 12-tone idea reached a tipping point) inspired a near-universal move toward social relevance and widespread appropriation of pop and world-music elements, a conviction that music should refer to the world and not only to its own processes. Totalism, the other big movement that branched off from minimalism, throve much better in the post-serial milieu, as evident in the more visible careers of the Bang on a Can composers. In many respects, postminimalism was an answer to serialism far more than minimalism was. The postminimalists, like the serialists, worked at creating self-sufficient and self-consistent musical languages, in this case a language in which the reduction of musical elements made musical logic apparent. The attitude was almost, "Let's do formalism over again and get it right this time, not anxious and apocalyptic and opaque like the serialists, but transparent and lyrical and pleasant."

By 1990, however, formalism of any kind was a hard sell. Justifiably tired of music that begged for technical analysis, the world wanted big, messy Julian Schnabels of music, not clean, pristine Bridget Rileys. It was, and remains, difficult to argue for music so focused on its own musical processes, no matter how pleasant to the ear. In fact, postminimalism's very pleasantness works against it: in the macho music world that John Zorn ushered in and the faux-blue-collar Bang-on-a-Canners have continued, postminimalism has never seemed kickass enough, its archetypes too feminine and conciliatory. (Kickass, kickass, kickass... I remember with perverse pleasure how ridiculously frequently that word came to everyone's lips in the New York scene of the late '80s, as though they had suffered some dire threat to their collective masculinity, and how easy it was to make fun of.) But pendulums swing, fashions change, and at some point the music world will remember that notes themselves can be made into patterns fascinating to listen to for their own sake. When that time arrives, the beautiful, varied, surprising postminimalist repertoire will be here to be rediscovered.

UPDATE: My little tirade above earned me a very funny comparison with Milton Babbitt via Darcy James Argue. Part of what's funny is that the Babbitt paragraph he quotes is one I happen to have always agreed with. Babbitt's a smart man, and not wrong all the time.

"Toward the seven deadly arts Sam had had the inarticulate reverence which an Irish policeman might have toward a shrine of the Virgin on his beat... that little light seen at three of a winter's morning. They were to him romance, escape, and he was irritated when they were presented to him as a preacher presents the virtues of sobriety and chastity. He hadn't the training to lose himself in Bach or Goethe; but in Chesterton, in Schubert, in a Corot, he had always been able to forget motors and [his competitor] Alec Kynance, and always he had chuckled over the gay anarchy of Mencken. But with rising stubbornness he asserted that if he had to take the arts as something in which he must pass an examination, he would chuck them altogether and be content with poker."

- Sinclair Lewis, Dodsworth

Hey, I got mentioned in the Times, in connection with Mark Morris. I love how the dance critics think the Disklavier is neat and sort of spooky, unlike musicians, who often see it as a problematic performance situation in need of rectification, somehow.

UPDATE: I can tell you why, as a composer, I prefer dance to theater. I've written for theater, and gotten always the same question, rehearsal after rehearsal: "Can it be softer?" Mark Morris asked if it could be louder, and I fell in love.

Two-movement form intrigues me, partly because there are so few two-movement pieces. Unlike three- and four-movement form, its paradigm is so far from being done to death that it is impossible to call any two-movement work typical - it still feels like partly unexplored territory. I love the Clementi two-movement sonatas, which come close to the most perfect balance in the genre, the movements differentiated in meter and density, yet weighted just alike; the Op. 33 No. 2 sonata in F major is the most exquisite case (though less well-known than the F# minor). The elephantine example, of course, is Beethoven's Op. 111, which is perhaps second only to the Concord Sonata as a work that hangs over my life. Other instances are easy to ennumerate:

Webern's Opp. 20 through 22

Nielsen's Fifth

Mahler's Eighth

Schoenberg's Chamber Symphony No. 2

Gottschalk's A Night in the Tropics Symphony

Copland's Piano Concerto

Bernstein's Age of Anxiety Symphony (actually six movements in two continuous parts)

the Becker Third Symphony.

(No one knows John J. Becker anymore, but when we dedicated New Music America '82 to Cage, Cage asked us to include a work by Becker because of his historical importance to the midwest. His Third Symphony is aptly regarded as his best work.) The two-part form of Beckett's novel Molloy, with the second half mysteriously parallel to the first, is an incredibly masterful new paradigm of the genre. Other examples that come to mind seem like cheating; Schubert didn't finish his Eighth, Schuman's Third is in two movements but each divides into two sections (like the Berg Violin Concerto), and the two Branca Symphonies, Nos. 8 and 10, are companion pieces, with four movements between them.

I find the simple duality of two movements inspiring: either this or that, black and white, happy and sad, before and after. Three-movement form is so classical, so easy with its matching fast bookends around an aria (or in Ives's refreshingly reversed slow-fast-slow pattern). By contrast, two-movement form defies you to find a balance. The very fact that one movement is first and the other last makes a true balance impossible; one of them will have the last word, and it can't refer back too much to the first movement and still achieve a satisfying diversity. The second movement's finality represents, in effect, the death of the first movement's idea, and it can't come back to life in the cheery third to make you feel better. These elements are not going to synthesize. One philosophy of life is going to win, and there's no escape.

Perhaps that's why it seems problematic. In 1994 I wrote a two-movement sonata for pianist Lois Svard, and it seemed like no performance would go by without someone coming up to me afterward and blithely telling me, "Great piece, Kyle. You oughta write a third movement." The second 15 people who said this to me never realized how close they came to being throttled within an inch of their lives. I had balanced those movements by making them the same length, but - perhaps thinking subliminally of Nielsen's Fifth, which I adore - I built up a great crescendo of energy in the first movement and slowly released it in the second. I never even had a glimmer of an idea for another movement: those two gestures were the piece, from its first conception. So either I failed to make my bipartite emotional arc convincing, or else my listeners were just so conditioned by the classical Oreo cookie with its creme filling in the middle that they were unable to quit waiting for the third shoe to drop. To mix metaphors.

And so, in my piano concerto, which is "about" Katrina's devastation of New Orleans - thus "before" and "after" - I'm taking a tip from Op. 111. The first movement is seven minutes long, the second somewhere between 16 and 20. I imagine that Beethoven (along with Mahler in the Eighth and Becker in the Third) realized that, to make the classical audience quit waiting for a reassuring synthesis, they had to be dragged through a mysterious, disturbing, second-movement landscape that would kill any yearning for a glib rondo. Where Beethoven's first movement is angry and the second transcendently accepting, my first is pure rowdy fun and the second devastatingly sad (before transcendent acceptance, of course). Like the first movement to the Ives Fourth, my first movement is almost little more than introduction, the setup for the devastation. As I see it, to cure the audience of thinking about third-movement symmetry depends on making the second sufficiently dreary, daunting, and disorienting (being only slightly tongue-in-cheek here) to make them forget there had ever been a first movement. And I swear to god that if people come up afterward and tell me it needs a third movement, I'll double the length of the second movement and only use the pitches C and D-flat in the second half. In whole notes. Pianissimo. Muted.

The remainder of May is hereby proclaimed Finish-My-Piano-Concerto-and-Get-On-with-the-Rest-of-My-Life Month, so don't expect much else from me. The job has taken on the terrible proportions of Alex Ross's recent book. I'm 18 minutes into a first draft with at least five more minutes to go, and then a deluge of polishing details. I'll tell you about it soon, but everything beyond its barlines is outside my focus for a while.

The world according to Wikipedia, as told by David Malki at Wondermark.com (thanks to B. McLaren):

I've finally figured out what I want to do when I grow up: write Disklavier pieces for dance. The music is irreproachably acoustic, the performances endlessly perfect and unchanging, the audience superbly friendly and impressionable, you get to watch nice-looking people transfer your rhythmic ideas into three-dimensional space in gestures surprising, comical, and poignant, and then you stumble onstage and bow at the end. What could possibly be better? The gratification-to-work ratio is through the roof. In fact, having seen the Mark Morris Dance Group perform to my music last night, I'm convinced now that dancers, as intermediaries, create a sympathy for the music that it could never inspire by itself. The audience enjoys the dancers, the dance is visibly indebted for its energy to the music, therefore, the music must be something special; or, perhaps, the dancers so underline the ideas in the music that they come across with an immediacy no simple audio presentation could achieve. In any case, I received an outpouring of enthusiasm from total strangers at intermission far beyond anything I'd experienced before, and that I don't believe could possibly result from a mere music concert.

My music has been choreographed a couple of times before, but never by someone who translates the music phrase by phrase with the thoroughness that Mark Morris does. Taking five pieces from my Nude Rolling Down an Escalator CD and repeating two of them, he fashioned a seven-movement dance called Looky all around the general theme of actors versus spectators. Tango da Chiesa became a group of people taking a tour through a museum as a guard sat idle but vigilant. Folk Dance for Henry Cowell became two rows of statues who surreptitiously changed position for each new group of tourists. Most hilariously, Bud Ran Back Out became a four-minute Western movie, with gun-slinging hero (female), Mae West-style hooker (male), poker game, floor show, drunk, and final gun fight in which everyone died but the principals. And in Texarkana, I saw my oh-so-clever 29-against-13 cross rhythms translated into arm and leg movements with a precision of which I thought only computers were capable. Those five pieces melded into a ballet with beginning, middle, and end, as though Mark was Martha Graham and I was Aaron Freakin' Copland. Never before has my music been so savored, so analyzed, so complimented.

Dance is the artform I least understand (I probably should harbor more of a grudge than I have against the pretty girl who told me in high school I couldn't dance and shouldn't try, for I took her advice), and I've never felt I possessed the vocabulary to distinguish Fred Astaire from Merce Cunningham. But I know what goes into my music, and to see dance come out taught me more about it than I'd ever known. What struck me most was how much Mark had to think, as much as any composer, in terms of time proportions. Some moments were drawn out in slow motion, others so hurried that I feared the music wouldn't be long enough, and I was quite impressed by the variety of tempos, and the counterintuitive imagination of Mark's pacing. Equally impressive was his associative imagination. I think of Bud Ran Back Out, my Bud Powell homage, as pure New York, but its transformation into a tawdry western was inspired. Mark also played a lovely joke with the Disklavier: the piece opened with 50 seconds of darkness, and the audience chuckled appreciatively when a spotlight faded on to reveal a piano playing by itself. But within 25 seconds, the simultaneity of independent lines in the high treble, middle register, and low bass implied the presence of at least three hands on the keyboard if any at all, and posed a conundrum for the ear.

Whenever I play those Disklavier pieces at a concert, a few people inevitably come up and irritatingly ask, "Wouldn't you rather have them played by a piano duo?" (As if that were possible. And the answer is "no.") But with the dancers providing the human element, no one asked any such thing. A good dance audience is amazing: they expect empathy and surprise, and, unlike a classical music audience, they are exhilarated rather than upset by divergences from traditional boundaries. Personally I think classical music audiences should be fed the uniform diet of endless Schubert they crave until they die, thus vindicating my friend Greg Sandow. But dance lovers aren't afraid of creativity and innovation, and these people, led by Mark's sensitive orchestration of my rhythms into movement, connected with me in a way no audience ever had before. It was extremely generous of Mark to share his perfect-vintage audience with me, as one would share a $200 bottle of rare single-malt scotch.

There are reviews in the Boston papers here and here. The climax of the concert was not Looky, but Grand Duo, set to a powerful, impressively memorable, emponymous work for violin and piano by Lou Harrison that seems not to be available on recording at the moment. If I thought I could do the dance justice in words, I would try. It was unforgettable.

I had five hours yesterday to program the Disklavier for Mark Morris's dance Looky, which is being performed to my Disklavier music tonight. Had I had a clue how Disklavier technology has changed in the last few years, I would have known I didn't need nearly so much. Yamaha used to employ a proprietary file format for the Disklavier. It wouldn't read standard MIDI files; you had to record a special Disklavier file by playing a MIDI file from your computer. It took me, Mark's excellent tech crew, and someone at Yamaha tech support two hours to learn that the new Disklavier grands won't even record a MIDI file from a computer anymore, so we had spent a lot of time trying to do the impossible. Instead, the Disklavier can now read MIDI files directly - and once we realized that, all I had to do was burn a MIDI file to a CDR and pop it in. It worked beautifully at rehearsal last night - as easy as playing an mp3.

The thing is, Yamaha gives the impression that it works according to a completely utilitarian paradigm: it sells (or loans in this case) these marvelous computerized pianos to schools and performance spaces for purely workaday purposes, like recording song accompaniments and providing background music. They no longer provide a manual, there's no how-to info on the internet, and the tech support people were difficult to reach because they were out traveling. There's no assumption that someone might be trying to transfer a file from an old Disklavier to a new one, nor that anyone might be trying to do anything more elaborate than pressing "record" and playing a tune on the keyboard. The idea that a composer might actually write pieces for the instrument and tour with them doesn't seem to have occurred to them. Still, now that Disklaviers read MIDI files they'll be a lot more versatile to use, and with luck - as long as they don't keep altering the way the thing works every year or so - I won't run into any of these problems again.

Geez, there are 18 dancers in Looky! It's like being played by a chamber orchestra, very exciting.

My arm twisted by my ACA chum Andrea La Rose, I went to hear Anti-Social Music in New York last night. I'm not going to review them, because the opinion-forming center in my brain burned out a few years ago and doesn't work any more. But I think I can convey in this space the extraordinary quality of their program notes, which give the appearance of having been produced in the same amount of time it takes to read them - as though they were read into a dictaphone hooked to a computer with instant voice-transcribing software. The general feel is not so much stream-of-consciousness as extemporization under extreme pressure:

Berry Seroff wrote Guitar Duo #2 for two rockin' guitars. I can't find any program notes for this piece, so I'll just say that Barry Seroff is a jerk who once shunned me on MySpace. Sure, he's befriended me since then, but the bruises will never heal....

Pat Muchmore is a complete douche bag, but sometimes he writes pieces too. This one is called:

[an ornate wordless diagram follows]

See what I mean?Peter Hess may or may not have written a Voiceprint. If he did, you should be hearing it now. If he didn't, you should be hearing the next piece. If you're hearing your mother's voice telling you to kill small animals, you are awesome....

Jean Cook has played violin since 1979. She recently started buying stamps online and thinks it's fabulous. www.usps.com

Brad Kemp (bass) would rather talk about YOU....

What can I say about Ed Rosenberg that hasn't already been said?

Scrapworm did the art. who is scrapworm? what's the point? a new worldview is possible. art is a function of such energies. activate the noosphere. resonate in the 5th day....

What can I say about Pete Wise (vibes) that hasn't already been said about Ed Rosenberg?

The ensemble patter between pieces was identical in tone and apparent speed. I enjoy these guys. Unlike classical composers they don't flash their credentials at you, but unlike rockers, they're not so cool that they have to keep mum and leave you wondering, either. The underlying message - "Who gives a shit where we went to college?" - is a healthy one for postclassical music. The patter filled up the spaces between the pieces and left no room for boredom. The show was a fast-paced circus, and the actual music, performed with an attractive looseness and the occasional rough edge, was interesting, savvy, and intricate enough to prove that the surrounding irreverent verbiage did not indicate any superficiality of compositional intent.

An incidental note to all those New York spaces whose managers think that the way to keep audiences entertained between pieces is to turn on recorded music in between the live performances: I hate you! I hate you! I hate you! Die! Die! Die! Anti-Social Music's solution was infintely smarter.

A comment from Scott, a former Bard student, brings to mind ideas about teaching composition that I wonder if anyone else shares. I've never heard of anyone being taught how to teach composition, except indirectly and by example. We're all winging it, aren't we? I had one composition teacher who never said a word I understood, and seemed to enjoy keeping me confused; another who disliked every piece at first and thought it was lovely as soon as you copied it out neatly; another who was brilliant but considered Cage and minimalism hoaxes; another who merely tinkered with my orchestration (Feldman); one who changed my life simply by telling me about just intonation (Johnston); and another who did me a world of good simply by enthusing about everything I did. Little of that activity seemed like teaching, though by default that's what we have to call it. I know of teachers who start out, "Here's how you compose a piece," and actually show you how to do it, step by step. I think that would have driven me nuts. It always seemed to me that what you mainly absorbed from an older composer was attitude, and you gravitate toward the attitudes that appeal to you.

Subsequent experience has suggested to me that there are two kinds of composition students: those who write too little music because they're too self-critical and those who write too much because they're not self-critical enough. (Those who write just the right amount are unheard of.) I feel much more useful with the ones who don't write enough, because that's the problem I worked through myself. First of all, I hardly make any suggestions on the first piece or two, because I need to learn what their reflexes and aims are before I can tell what they're trying to do and figure out where they're not succeeding. Then, when I see them turn down the same road a third or fourth time, I can say, "Aha! You always do that, don't you?" Not to prevent them, but just to make them conscious. Sometimes I'll play them, and analyze a little, pieces that do something similar. In rare cases, if they're really stuck, I'll assign specific compositional problems to attack (like, write a trio only using five pitches). I've only had one case in which that strategy really lit a fire under the student; more often, they start composing their own pieces faster to induce me to stop.

Typically I try to isolate the essential idea of a piece and write my own little variations on it, to look for ways to continue. Sometimes, like all composers, I'll pull out a piece of my own, show the original problem I struggled with, and show how I solved it. I almost never write notes on their score, because that drove me nuts when I was a student. But I love taking their Sibelius files, "saving as" something else, and tinkering with changes. Occasionally they like the changes, but it seems to me that most of this activity simply serves to focus them and make them think harder once they leave my office. As an ongoing influence, I harangue them to turn off their superegos, to silence the constant critical carping in the back of their minds that tells them, as soon as they've written three notes, that those notes aren't good enough, that compares every line they write with Bach and finds it wanting. If they can do that, they can do anything. Sometimes, if they're obsessed with a certain composer they worship, I'll forbid them to listen to that composer any more. I had to quit listening to Cage in college for that reason.

The students who write too much are much harder for me. They often come in with a new completed piece every week, which suggests a certain success that's hard to argue with. It's difficult to convince them that revision is golden, that even when it's going well you shouldn't always settle for the first idea that presents itself. And then, there's little opportunity to direct the course of a piece when it comes in with the final double bar already in place. Of course, like all composition teachers, I pound away at notation, and describe at length how performers respond to, especially, rhythm and articulation markings. That's the easy part, though they won't always believe that you can't start a 4/4 measure with an 8th-note followed by a half-note. My teachers' generation often taught little besides penmanship and types of manuscript paper. Similarly, I end up teaching the finer points of Sibelius (the software).

I've taught mostly undergrads, and am happy with that, because they're more pliable and need more advice. What I'm not sure is practically helpful is trying to prepare them for the way a composer's process changes with the years. I think it seems pretty well established - though I don't know that I've ever read this anywhere - that young composers tend to get inspired by a sonic image and then just start out without knowing where they're going. At some point, in a person's 20s or 30s, those sonic images become less spontaneous, and it seems to me that a composer has to learn to quit waiting for that inspiration. Typically, I think - and I ask this as a question - college age composers tend to have tremendous bursts of inspiration, and be almost incapable of composing when not inspired. As your psychology changes in your 20s, you start thinking less of individual moments (or melodies, or motives) and more about strategies for entire pieces (like chord progressions or rhythmic structures). Then it becomes easier to just sit down and start writing, inspired or not, and at some point inspiration creeps in and lifts the piece off the ground.

I've interviewed dozens of composers for my articles and books, and I've heard one process described over and over again. A young composer will find some method to generate his music, and use it strictly. At sometime in his 30s, he or she will have internalized the method enough to quit using it consciously. My favorite example like this was Petr Kotik, who, in his early years (Many, Many Women is the famous example) based all his melodies on graphs he had found discarded in a science department that showed the rates of alcohol-level response in experimental rats. For years all his music went back to those found graphs as a kind of chance process based on "found" contours. Then, he said, at some point he learned to intuitively write melodies that had those characteristics without using the graphs anymore. I think you find the same pattern - overly strict at first, then later freer and more intuitive - in most of the good serialist composers, Boulez and Stockhausen in particular. Then, many composers also go through another tremendous shift during their 40s, in which many of the compositional ideas they studiously avoided in youth begin to appeal to them, and their music finds a whole new level as they start playing with the devices they swore they'd never use. It certainly happened to me, when around 1999 I started allowing myself to borrow stylistic paradigms from jazz and other composers. (Make sure to shy away from some great ideas when you're young, so you'll have great new toys to play with in old age. I have an article in Music Downtown. "Mistaken Memories," quickly tracing this phenomenon through a wide range of composers.)

As I say, I don't know to what extent it helps a young composer to be aware of the eventuality of these changes coming in later in life. I like to think that they'll accept the changes more easily if they know it's a lifelong process of evolution, that they won't get stuck clinging to the process that always worked in the past. The most important thing of all, I think, is to get them used to the process of trying to extend their technique into some area they've never tried before, getting stuck, feeling helpless, and just living with their failure until some imaginative breakthrough suddenly makes them see where their imagination had been too limited. It's a process that can cause considerable despair when young, and, as you gain experience, you learn more (or I have) to accept that "stuck" feeling as the necessary prelude to a creative breakthrough.

These, off the top of my head, are my thoughts about teaching composition - almost as much, or more, a process of emotional therapy than actual musical instruction. I am curious as to whether other teachers find this same dichotomy between young composers who write too little and those who write too much. I wonder if other composition professors muse as often as I do that training in psychotherapy might have been more helpful for this line of work than musical training has been. And I wonder if the process of "switching gears" in your 20s, relying less on sudden inspiration because it doesn't come as often and you no longer need it so much, is as universal as I imagine. It seems to me that we composers don't talk about these processes enough, that we all live in ignorance, blindly feeling our way, having to figure out how it works through self-examination and anecdotal evidence. Perhaps the blogosphere is the arena in which to shed some light on the categories of artistic evolution. I yield the floor.

I have an interesting and unusual student graduating this year whom I'm fond of, and I don't think he'll mind my writing about him here. Coming to college later than most, he was blown away by 16th-century counterpoint early in his education, and his music has remained intransigently tonal. In his more characteristic moments it begins to resemble the sustainedly consonant music of Arvo Pärt, with the same kind of self-conscious spirituality; at other times, it resembles a kind of diatonic romanticism, veering close to John Williams-type film music.

One of my colleagues, with whom I had a mild and friendly disagreement about him, considers it a problem that this student doesn't seem to have absorbed the music of the 20th century - meaning, of course, dissonance, atonality, abstract structural techniques. I pointed out that not only has Pärt made a career out of diatonic music, but that one of the most widely-performed orchestral works of our time - Tobias Picker's Old and Lost Rivers - is entirely couched in the D-flat major scale, with only one accidental in the entire piece, a D-natural in the violins. If living composers as disparate as Pärt and Picker can become incredibly successful staying within a single diatonic scale, who am I to tell my student that what he's doing isn't "modern" enough?

Of course, I am also sympathetic to my colleague's point. A student composer should learn some versatility in college, and trying out different styles is part of the process of finding one's own voice. (God, I hate that facile, heavily-laden term "a composer's 'voice,'" but that's perhaps a subject for another day.) My colleague teaches a course in which students practice composing in the style of various 20th-century composers. But I tried many times to write a 12-tone piece in college, and could never manage to finish one. The limitations seemed arbitrary and ridiculous. I was the type of student for whom composing in a style I couldn't feel as my own would have seemed a wasted enterprise.* Consequently, I feel that the place to expose students to 20th-century styles is in theory class, not composition lessons, and I try to make all the composers take my course "Analysis of the Classics of Modernism," which starts with Socrate and The Rite of Spring and runs up through Rothko Chapel. I take them inside works like Gruppen, Quartet for the End of Time, Bartok's Sonata for pianos and percussion, and Nancarrow's Study No. 36, and figure, if they find anything that attracts them, they'll incorporate it into their own music. I try not to send a message that this is how you're supposed to compose - my emphasis is more, these are things that have already been done.

Of course, the bigger picture, as my colleague pointed out rather glumly, is that there is no longer a single route to one's own musical style. What we call "20th-century music" is now a historical period. Why, at this point, is it any more necessary that a student composer internalize Messiaen than Brahms? What does either composer offer the 21st-century sensibility - or why not Brahms as much as Messiaen? My students may come up through Bartok and Stravinsky, but they are just as likely to arrive at their musical taste via Pärt and Reich; or Eno and Captain Beefheart; or Bjork and Sigur Ros; or Sun Ra and Ornette Coleman; or Sibelius and Britten. There is no longer a privileged mainstream. Yet what are we professors here for, except to lead them through some tradition they would never have discovered on their own?

And aside from their starting point, what about their ending point? It strikes me that my "conservative" student might do well writing film music, and even better tapping into the huge choral market that most college-trained composers bypass. Knowing as I do how few resources there are for the ambitiously avant-garde composer these days, why would I try to funnel him into the life of the same kind of "professional" composer as myself? I do tell him that he's not going to make it in the academic composing world writing whole-note triads and elegantly resolved suspensions, and he gets it. But if he can head off to Hollywood and write like John Williams, why would I deflect him? Or if he's one of the few people with smooth enough contrapuntal technique to compete with someone like Morton Lauridsen on the choral circuit (where copies of a singable psalm can well sell in the 25,000 range), why would I deflate his marketability by pressing him towards "modern" techniques that even I consider dated? Not every composer is aiming at Guggenheims, orchestral residencies, a Harvard teaching gig, and the Pulitzer Prize. Excuse me, I meant to say the goddamned Pulitzer Prize (which I'm certainly not aiming at myself, either).

At the heart of all this is something I wrote about recently, that professors desperately yearn to feel useful. We want to pass on what we know that was useful to us - and yet it comes so soon that the creative student is involved in a world in which our own knowledge becomes irrelevant. Of course it's crucial that the student become conversant in the body of 20th-century music and its ideas of structure and method. It's just a historical period, though, a toolbox of techniques. For that matter, last month was a historical period. In what possible way does it obligate us this month? "We are not slaves of history," George Rochberg wrote; "we can choose and create our own time." There is the dismaying possibility that a young composer will become a slave to the 19th century, or the 18th, or the 16th. I regret that, but why substitute one period of slavery for another? I do not agree with my colleague that a composer is under any constraint to write music "of his own time" - "his time," that is, as defined by the ubiquitous clichés of the all-too-conformist composing fraternity. "Let no year go by," intoned the great Harry Partch, "that I do not step one significant century backward." We in the classical composition world cherish a little-examined theory that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, that each student finds him- or herself by working his way up through the history of music (as indeed I did myself, from Copland to Harold Budd). But whose history? Which history? Some of my students are recapitulating histories that I've never lived through.

Another of my students wrote an "opera," in the most unconventional sense, which turned out to be quite original and interesting. At a faculty board he said that he didn't know anything about opera, but decided to try one anyway, and all three of us agreed that it seemed to be a good thing that he didn't know anything about opera, because those who do know about opera tend not to come up with as intriguing results. And I thought, What am I doing here? If ignorance and experimentation, mixed with energy, are such fertile ground, why am I trying to remove the first and set limits to the second? Of course, I'm not, really. As a scholar I provide background which ought to be interesting to anyone, even if not useful. As a composition teacher (such a common oxymoron) I'm here to provide assistance when asked for, and as a reality check. And when the student is propelled by his or her own enthusiasm - even if it leads to music that sounds like Bach - I do my level best to stand out of the way.

*[Of course, the irony here is that since I hit my 40s I've taken a Stravinskian glee in imitating the styles of Billings, Brahms, Bud Powell, Jelly Roll Morton, James P. Johnson, and so on.]

One of my coolest gigs ever begins a week from tonight. Mark Morris (pictured) has choreographed a dance called Looky to five of my Disklavier studies, and it's being presented at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Boston. Performances are May 15, 17, 18, 19, and 20, and I'll refer you there for location and times. Because the commission was for a Museum (the ICA), Mark has supposedly made the dance about looking at paintings in a museum, thus the title Looky - cute, huh? Mark is famous for using live music for his dances, and this will be presumably the first dance involving a "live" Disklavier as accompaniment. (Even Yamaha, who makes Disklaviers, has gotten involved in publicity, which is more than they'd do for my CD last year.) The other composers represented on the program - and pardon me for savoring this for a moment, since I may never get to write another sentence like this in my life - the other composers represented on the program are Schumann, Stravinsky, and Lou Harrison.

One of my coolest gigs ever begins a week from tonight. Mark Morris (pictured) has choreographed a dance called Looky to five of my Disklavier studies, and it's being presented at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Boston. Performances are May 15, 17, 18, 19, and 20, and I'll refer you there for location and times. Because the commission was for a Museum (the ICA), Mark has supposedly made the dance about looking at paintings in a museum, thus the title Looky - cute, huh? Mark is famous for using live music for his dances, and this will be presumably the first dance involving a "live" Disklavier as accompaniment. (Even Yamaha, who makes Disklaviers, has gotten involved in publicity, which is more than they'd do for my CD last year.) The other composers represented on the program - and pardon me for savoring this for a moment, since I may never get to write another sentence like this in my life - the other composers represented on the program are Schumann, Stravinsky, and Lou Harrison.

So eat my shorts.

Nah, I didn't mean that.

[Writing new book in head:] One of the problems in discussing minimalism clearly is that the word gets used in a few different senses. Judging from recent debates on the subject, I'd say it has three interrelated meanings:

1. Minimalism was a movement of people who knew each other, worked together, influenced each other, and created variations of a particular common language. In that specific sense, the movement began with La Monte Young's String Trio of 1958 and lasted until the late '70s, or certainly no later than around 1983. Pronouncements that minimalism is dead began around 1978 - I was there - and are only meaningful insofar as the word is applied to that definable scene.

2. Minimalism is a style of music based in audible structure and relative stasis and/or slow transformation. In this sense, certain composers, such as Phill Niblock and Tom Johnson, have continued writing minimalist music up to the present day. Some would say the same of Reich and Glass, both of whom, however, have claimed that around 1980 their music quit having anything to do with minimalism strictly speaking. One can argue, then, that a piece made outside the 1958-1983 time frame - say, Carl Stone's Shing Kee - can be referred to as minimalist, despite the fact that Stone was too young to be involved in the original movement. I've described the outlines of this style at greater detail in a New Music Box article that won a Deems Taylor award and got reprinted in the book Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music, so I am led to conclude that my views on the style do not lie outside the mainstream of scholarly understanding.

3. Minimalism is also more vaguely ascribed to any piece that sustains a specific texture, rhythm, tonality, and so on, from beginning to end. In this sense it is often said that Feldman was a minimalist, that certain pieces of John Cage are minimalist, ditto for pieces by Erik Satie and Federico Mompou, Gregorian chant and gamelan music and a ton of pop music all turn out to be minimalist, also the C Major Prelude from the W.T.C. Book I and many of Schubert's songs, and in fact we find minimalism traversing all centuries and many styles. And let's never, never neglect to mention the first six minutes of Das Rheingold - which, once it finally modulates (or resolves) from E-flat to A-flat at the entrance of the Rhinemaidens, sounds in retrospect just like an inordinately prolonged dominant preparation, about as relevant to minimalism as the Eroica Symphony is.

The first two meanings are what I think of as the scholarly, precise connotations of minimalism. The third sense looses the word from its historical referents and renders it a universal quality, like romanticism or classicism. We can find romanticism in the medieval epic The Song of Roland, or the music of Messiaen, works that lie well outside the boundaries of what has been defined as the Romantic Period, and we can contrast romanticism with classicism in any historical period. We have a long cultural tradition of what romanticism and classicism mean, so that arguments imputing those two qualities to various works of art are subtle, polemical, not simple, and carry a lot of historical weight.

I don't believe it is clear yet that minimalism is going to evolve into the same kind of term. We can call Gregorian chant minimalist, but in that sense the word becomes something of a tautology; that is, the general qualities we associate with minimalism in the broad sense predate the actual historical style by centuries, and were once taken for granted. Unchanging texture and tonality became strikingly associated with minimalism only because the contrast with the musical complexity of the previous century and a half was so dramatic. The qualities of romanticism (emphasis on the individual, subjective, spontaneous, and visionary against the idea of rationally imposed order) and classicism (the dependable restoration of harmony, clarity, restraint, and universality) can be spoken of as innate impulses within the human soul. It's not at all obvious that minimalism's relatively extreme limitations of texture and tonality are ever going to achieve any similar psychological status. There's nothing wrong with using minimalism this way, so long as the user understands that the burden of proof is on him to make a case for some universal applicability of the word. Most instances of such use, however, just strike me as intellectual laziness - anachronisms fallen into by people who are so little familiar with music outside the European common practice period that they are naively surprised to find texturally static music in any other milieu.

Another complicating factor is that many amateurs are only familiar with the tip of the minimalist iceberg - i.e., the works of Reich and Glass plus Riley's In C - so that repetition becomes minimalism's defining feature. Were one familiar with other minimalism of the 1960s - the droning improvisations of the Theater of Eternal Music, Niblock's slowly moving drones, Young's sine-tone installations, Jon Gibson's and Barbara Benary's change-ringing note permutations, and so on - it would become clear that repetition is only one strategy in minimalism's arsenal, and not the sufficient core of a general definition.

An additional problem with taking staticness as the primary criterion is that minimalism grew out of a conceptualist movement started by Cage, whose works tended to be calculatedly static over a period of time. Minimalist music shares its static quality with many works by Cage, Lucier, Ashley, Berhman, Feldman, Wolff, Mumma, and others that predated or were contemporaneous with the minimalist movement; but minimalism self-consciously differentiated itself from that music by embracing various techniques of audible process, in fact deliberately rebelling (as Reich's early writings document) against the hidden quality of Cagean processes. Without taking that differentiation into account, one arrives at a version of minimalism that inaccurately represents what was going on at the time.

Add to this that we now have an entire generation that has come to minimalism through its reuse in DJ music, remixes, ambient music, and so forth, so that there is now a widespread popular image of minimalism that is only a rough caricature of the way the movement looked to those of us who followed it as it was still going on. This will all pass. Until it does, though, I think it's impossible to imagine that any meaningful definition or description of minimalism could be achieved through the consensus of people unfamiliar with the issues, repertoire, and writings of the range of composers involved in the movement itself.

I've seen the light on Wikipedia, and I feel like a fool. I've used it, praised it, and, determined populist that I am, extolled it here as a model. I'm probably one of the few professors who has talked it up to his students and allowed them to cite it as a reference - carefully, with outside confirmation if possible, and judging the quality of an entry carefully. I started contributing to Wikipedia as a kind of spare-moment hobby, and I guess I was lulled into complacency by the fact that most of the entries I worked on were obscure ones, not likely to attract attention. But I had the temerity to do a little badly-needed clean-up on the dismally confused "Minimalism" entry, and learned more than I wanted to know about how the site operates. The articles that a lot of people think they know something about, it turns out, are a nightmare. I take back everything: Wikipedia is a playground for belligerent adolescents.

What pushed me over the edge was that a kindly editor finally directed me to a policy page called Expert retention. (One thing you've got to hand the Wikipedia community: they take self-analysis and self-examination to levels Socrates would have envied, and the site's every foible is analyzed to within an inch of its life.) It turns out that Wikipedia has a difficult time holding on to experts to edit their articles. The site, with its ever-present Wikimania for lists, lists many scholars who have given up on the site, many more who are discontented, and only two who are happy with the status quo. The vandalism problem has received a lot of publicity, but that one's actually fairly minor, or at least relatively fixable. More aggravating is "edit creep," the gradual deterioration of a polished article by well-meaning but careless edits, and, even worse, "cranks," which are classified with typical Wiki-precision as "parasites, scofflaws or insane." And a crank can single-handedly destroy an article's usefulness.

The problem is that Wikipedia forces its contributors to come to a consensus, and building consensus with a crank is a fool's errand. Many of the departing scholars note the incident that finally brought them to leave; mine was a truculent teenager who refused to acknowledge that minimalist music was considered classical, because, as he put it, "it sounds more like Britney Spears than like Merzbow." Let that sink in a minute. A person who insists that Einstein on the Beach, or Phill Niblock's Four Full Flutes, or Tom Johnson's Chord Catalogue cannot be considered classical because it sounds like Britney Spears is not a person one can seek consensus with. Because of that and his flippant rudeness I refused to argue directly with him, and appealed to the Wiki editors. Yet because of the Wikipedia policy about consensus, I couldn't get around him, either. And when I checked the "Expert retention" page, I realized that this was not an isolated bit of bad luck, but that this recurring problem bars the dissemination of knowledge throughout Wikipedia.

Wikipedia is amateur-friendly, and that's what I liked about it. Too many print reference works are hobbled by the exclusion of scholars and thinkers who are ahead of the curve, whose ideas (and even entire categories of knowledge) are not countenanced in the stodgier university departments whence many reference works depend. But Wikipedia is not only amateur-friendly, but expert-unfriendly. They pretend not to be, and give lip service to the importance of expert editors. But when you put the rules together, you realize that people who are actually authorities on a subject are forced to argue with one hand tied behind their backs.

For instance, there's an "original research" rule: original research, i.e. facts you've dug up or deduced yourself but that are not verifiable in the scholarly literature, are not allowed. Well, I can see that. You don't want every unpublished crank using Wikipedia to propagate his crackpot views. Most of what I do is original research, since I rarely write about things other scholars have already covered, but that's all right, since I've published most of my research, and all I have to do is footnote my own books. Ah! but there's another rule called "Conflict of Interest," which disallows quoting yourself for the purpose of bringing public attention to your writings. Which means that any other person on the planet can write something in Wikipedia and quote me as an authority, but if I do it myself, that's suspect. I have done it myself, and the citations stand if no one objects, but if a crank wants to contradict me, all he has to do is yell "Conflict of interest!," and delete whatever he wants. After all, who knows what scruffy, fly-by-night vanity presses my books might be issued by (Cambridge University Press, Schirmer Books, University of California Press)? Editors are sympathetic - everyone agreed with what I was saying except this post-pubescent parasite - but rules are rules, and nothing could be done. There's even an official "Ignore all credentials" policy, which explicitly disallows a writer's credentials from being taken into account. I thought I was egalitarian enough not to mind. Turns out I'm not.

So the "Minimalism" article is wretched, and so it will remain. When I came to it, one of the definitions given was "From hippie to yuppie[,] minimalism is a drip-feed pseudo-art for cultural bottle-babies." That no one objected to. I removed Petr Kotik from the list of minimalist composers, for the minor reason that there is nothing minimalist about his music, and there was a vehement protest. I removed a statement that minimalist pieces are known for their brevity, and there was a protest. Then I ran into the moronic crank, who wouldn't agree that minimalism was the most controversial movement in recent classical music on the grounds that it wasn't classical. He stonewalled. How can one verify that minimalism is part of classical music? No reference work will state as much, because everyone with an above-80 I.Q. simply knows it. I could have overlooked that and gone on, but the "Expert retention" page informed me that such problems are endemic throughout Wikipedia's warp and woof. There is an apparently famous case in which one amateur crank defeated a group of professional scientists trying to describe facts about uranium trioxide. It's kind of an intellectual's worst nightmare: you find out your new editor is the dumb bully who used to beat up on you in seventh grade - and he hasn't changed in any respect! He's still in seventh grade, and imagines you are too.

And so I'm off Wikipedia. What's more, now that I know how the background process chases away experts, I can no longer allow students to cite it. I'm holding out some hope for Digital Universe, which has been designed to elicit expert writing in order to circumvent such difficulties. Meanwhile, I have actual books to write, with adult editors willing to take my word for something. Between my Simpsons videos and The Comics Curmudgeon, I don't need to spend my spare moments building sand castles of knowledge on a heavily-trafficked beach.

UPDATE: Forgive me for turning off the comments here, but some Wikipedians (Wikipediots?) are beginning to come here to continue arguments started over there, and, not having any earthly idea who's right and who's wrong, I don't want to get stuck refereeing. The site clearly stirs violent emotions, sufficient reason for me to keep well away from it.

Let me say that again:

(AP) -- The National Rifle Association is urging the Bush administration to withdraw its support of a bill that would prohibit suspected terrorists from buying firearms.

The next time Democrats are portrayed by Republicans as aiding and abetting the terrorists, turn to someone near you and remind them about this.