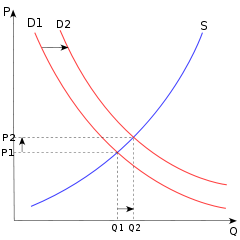

I’m ready to take a break from the supply/demand discussion, at least for a while. As I’ve been thinking about it I find that other work I’m doing is refracted through the lens of that discussion.Â

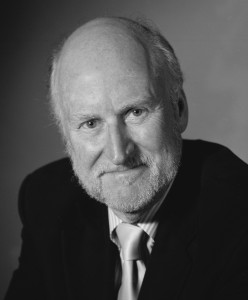

One such item is an article that Russell Willis Taylor recommended to me and I’m passing it along to all of you. It’s called No Big Deal, by Thanassis Cambanis, and was published in January in the Boston Globe. Cambanis writes about the Columbia University economist Scott Barrett whose research looks at the history of success or failure in resolving large-scale global problems — problems that cannot be solved by the efforts of any single nation.

Barrett’s research shows that modest and incremental efforts have resulted in lasting change in instances where global, comprehensive agreement cannot be reached.  Barrett’s analysis of a century of human problem-solving concludes that holding out for the negotiation of  “grand bargains” is tactically less promising than working on a “piecemeal approach” (Cambanis’ language in quotes).

This roughly parallels my own experiences in implementing change — that little steps add up to big steps, and it’s faster, to boot.  Consistent momentum in small steps is nearly always easier than sweeping change in grand gestures. People and systems are also less stressed by incremental change than by sweeping change, and we can see the evidence of this in politics, business, nonprofits and in our personal lives. Neuroscience tells us that the brain experiences change as pain. The leader’s challenge is bring about the necessary change while being mindful of ways to minimize pain and therefore resistance.  (See The Neuroscience of Leadership by David Rock and Jeffrey Schwartz to read more about this. The site requires free registration.)Â

So, while it is interesting to think about a grand re-drafting of the systems in place that inhibit the fullest expression of the arts and culture, research points us in a different direction. We will get about the work faster and be met with less resistance if we plunge in and begin the work in little but persistent steps.  If applied to the national conversation we are having about the relevance and vibrancy of the nonprofit cultural sector, we can look to the incremental steps that artists and organizations are taking now that will add up to sweeping change in the coming years. I would argue that changes in interactivity with audiences, in fresh approaches to community engagement, in the re-thinking of organizational structures, in the use of digital tools, and in the processes of artmaking all are proceeding creatively and effectively within our sector, and that these many small steps are adding up to big change. Do you see this, too?