As I’ve watched museums over the past several months as they curate shows from their own  collections and sometimes from private collections nearby, I’ve had a sneaking suspicion that there’s a big downside to this as well as an upside.

collections and sometimes from private collections nearby, I’ve had a sneaking suspicion that there’s a big downside to this as well as an upside.

The upside, of course, is that many visitors go to museums only — or mostly — to see the special exhibitions, leaving permanent collection galleries empty of visitors. Exhibits curated from permanent collections will expose those works to more people and perhaps entice visitors into permanent collection galleries on a regular basis.

The downside, which I confirmed this week, is that many exhibits are going without the preparation and publication of catalogues.

Consider an exhibit that the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, opened in December: Object, Image, Collector: African and Oceanic Art in Focus. According to the press release, the exhibit

traces the ascent of African and Oceanic objects from artifacts to works of art in the 20th century, drawing on 20 Boston-area collections and on the collections of the MFA. Besides presenting some 60 three-dimensional works and textiles of excellent quality, the exhibition also examines the role of photography and photographically illustrated books in promoting this shift in appreciation of pieces from Africa and Oceania.

But it has no catalogue — just a color brochure.

But it has no catalogue — just a color brochure.

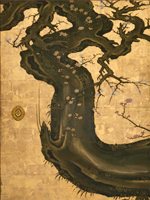

The Metropolitan has not published a catalogue for 5,000 Years of Japanese Art: Treasures From the Packard Collection and small, exhibitions built around a masterpiece or two, like The Milkmaid, aren’t getting catalogues either.

These are just a few examples. So I ask, are we losing scholarship here? Without catalogues, will those people who buy catalogues learn less? Will we lose permanent records of these exhibits?

We may well. Catalogues are expensive – $50,000, $60,000, and sometimes often (usually?) much, much more. (See comment, below.)

On the other hand, the Philadelphia Museum of Art is probably blazing a trail for its coming exhibit, Picasso and the Avant-Garde in Paris. There’ll be no “hardcopy” catalogues — but the museum responded to my query today by saying it will publish an online catalogue, “including all of the works in the museum’s permanent collection.” (More details as I get them.)

Auction houses and some galleries have been using very good technology for online catalogues for ages now, of course. For just one page-turning example, take a look at Jill Newhouse’s digital catalogue for Wolf Kahn’s Early Drawings.

UPDATED, 1/8: I asked Jill about the costs for the Wolf Kahn digital catalogue, which she put at about $3,500 plus a small monthly fee. She also referred me to her designer, Larry Sunden, who adds that all one has to do to use PageGangster, the site that published the Newhouse catalogue, is create a PDF and upload it. PageGangster does the rest for $200 and a monthly fee ($10 or so) to add the page-turning and other features and to store the catalogues on their server. Pretty simple. Newhouse is also doing one for her coming Master Drawings exhibit.

And here’s a tale: Some scholarly publishers have learned that online publication actually led to an increase in demand for hardcovers. Once people had perused contents, they wanted their own copies.

Photos: Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts (top); Metropolitan Museum (bottom)

Museums’ financial difficulties aren’t going away in the near future, and neither are deaccessioning controversies, and that’s why I wrote an op-ed for The New York Times, which published it in Saturday’s paper as “

Museums’ financial difficulties aren’t going away in the near future, and neither are deaccessioning controversies, and that’s why I wrote an op-ed for The New York Times, which published it in Saturday’s paper as “