For some reason I cannot fathom, I’ve been receiving many press releases lately about museum acquisitions, by gift or purchase, and in one case, about a wonderful gift to make acquisitions. I hope they keep coming!

Let’s look at them in reverse chronological order:

This morning came news that the Art Institute of Chicago received more than $35 million designated to the purchase of new works in its Prints and Drawings and Asian Art departments. It came from a long-time benefactor named Dorothy Braude Edinburg who, in 2013, made “a landmark gift of more than 1000 works of art” and “established the Harry B. and Bessie K. Braude Memorial Collection in her parents’ honor.” The collection consisted of European prints and drawings, Chinese and Korean stonewares and porcelains, and Japanese printed books. More details here.

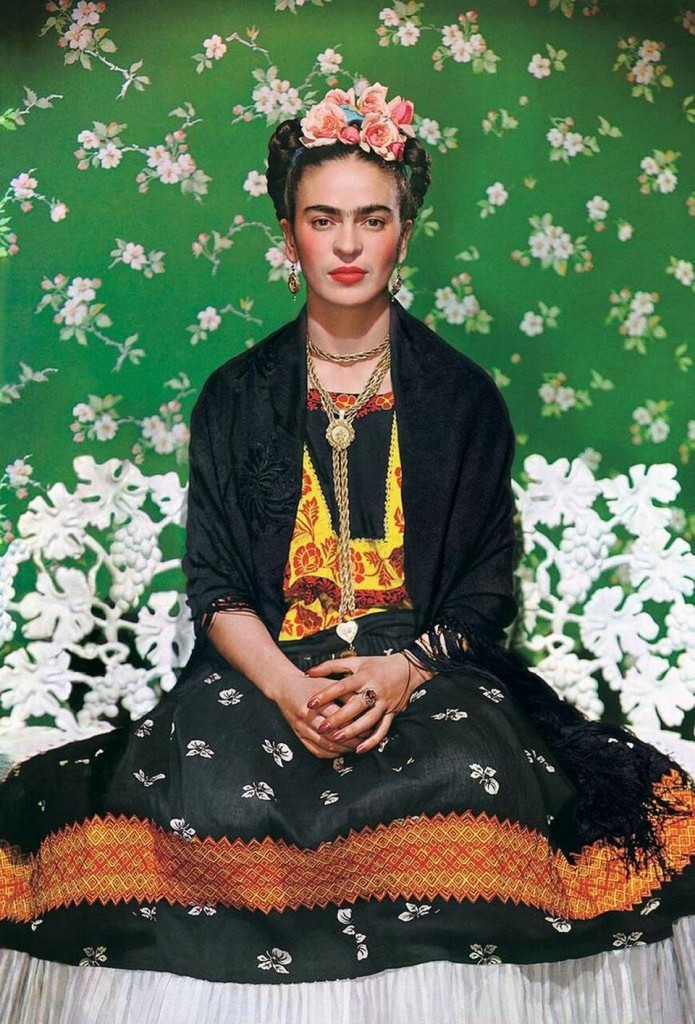

Yesterday, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston announced that it had purchased its first work by Frida Kahlo–not the most representative of her work but important because it was the first painting she ever sold. “Dos Mujeres (Salvadora y Herminia)†was painted in 1928 and portrays two maids that Kahlo knew, set against tropical foliage. More details here.

Yesterday, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston announced that it had purchased its first work by Frida Kahlo–not the most representative of her work but important because it was the first painting she ever sold. “Dos Mujeres (Salvadora y Herminia)†was painted in 1928 and portrays two maids that Kahlo knew, set against tropical foliage. More details here.

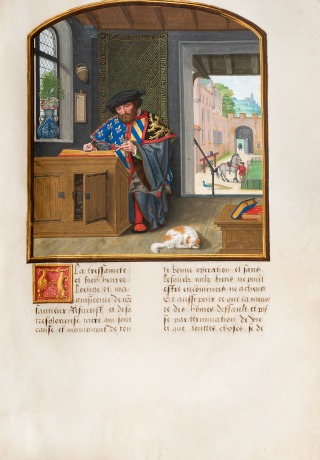

The Getty Museum also landed a treasure (at left), announcing that it had acquired a rare Flemish manuscript. It requires a quoted description:

Livre des fais de Jacques de Lalaing (Book of the Deeds of Jacques de Lalaing), a highly important illuminated manuscript comprising text by Jean Lefèvre de Saint-Remy and a frontispiece by Simon Bening, the leading Flemish manuscript painter of the period. The manuscript also contains 17 lively miniatures attributed to an anonymous painter in the circle of the Master of Charles V. The Livre des fais de Jacques de Lalaing is considered one of the greatest secular manuscripts produced during the last flowering of Flemish illumination in the second quarter of the 16th century. The vivid illuminations, rendered with remarkable detail and vibrant colors, extol the ideals symbolizing the age of chivalry.

Nicely, the piece was bought in honor of recently retired Thomas Kren, the senior curator of the Department of Manuscripts there from 1984 – 2010 and then Associate Director of Collections. More details here.

In mid-January, the very lucky Getty also acquired–part purchase, part gift–31 pieces of 18th century French  decorative arts from the collection of Horace Brock. More details here.

In Pittsburgh, the Mattress Factory announced a dandy gift: James Turrell has donated a Skyspace with an estimated worth of more than $1 million. The museum did not announce the size and shape of the piece, probably because Turrell must yet design it and, maybe more important, the Mattress Factory has to raise funds to pay for the work’s installation. More details here.

In Pittsburgh, the Mattress Factory announced a dandy gift: James Turrell has donated a Skyspace with an estimated worth of more than $1 million. The museum did not announce the size and shape of the piece, probably because Turrell must yet design it and, maybe more important, the Mattress Factory has to raise funds to pay for the work’s installation. More details here.

Yesterday, the Huntington announced several acquisitions by its Collectors’ Council, including some art works (the library took in two large archives):Â collection of 19th-century images that trace the history of photographic practice in the American West, a rare, annotated Latin manuscript about the Three Magi, Â written on parchment and produced in England between 1400 and 1450. More details here.

Earlier this month, the Cincinnati Art Museum said it had acquired The Wilderness, an 1861 landscape by Sanford Robinson Gifford, and a life-size glass sculpture, Seated Dress with Impression of Drapery, created in 2005 by Karen LaMonte (at right). More details here.

That’s a pretty great list, going back just two weeks. And I probably some as not every museum sends me such announcements.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Getty (top) and the Cincinnati Art Museum (bottom)