Steve Wynn brought out his checkbook again last night, and paid an eye-opening $12,8 million for a set of four Empire ormulu-mounted Chinese porcelain baluster vases, including the buyer’s premium. Christie’s had set the presale estimate, minus the premium, at $961,200 to $1.6 million.

The four-foot high vases, which date to the Jiaqing period (1796-1821), with mounts circa 1815, once belonged to the Dukes of Buccleuch. The family sold them at Christie’s in 1973, and they were resold at Bonhams in 1980.

The four-foot high vases, which date to the Jiaqing period (1796-1821), with mounts circa 1815, once belonged to the Dukes of Buccleuch. The family sold them at Christie’s in 1973, and they were resold at Bonhams in 1980.

It was a shrewd purchase, even at that price. According to Bloomberg,

After the auction, the casino-owner’s leisure group said the vases had been bought by Wynn Resorts Macau Ltd. for its new Cotai Resort Hotel, scheduled to open in 2015. It was also the buyer of a Chinoiserie tapestry for 169,250 pounds.

“We are delighted to return works of this extraordinary quality to the city of Macau and the People’s Republic of China,” Roger Thomas, executive vice president of Design for Wynn Design and Development, said after the sale.

Talk about currying favor and good will — and a new reason to exceed estimates.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Christie’s

According to his MFA bio:

According to his MFA bio: It is exactly the kind of show the Whitney should be doing, far more often than it has done: one that makes a definitive statement, showing the full range of work of an artist whose reputation is not what it should be or who (perhaps) isn’t well known.

It is exactly the kind of show the Whitney should be doing, far more often than it has done: one that makes a definitive statement, showing the full range of work of an artist whose reputation is not what it should be or who (perhaps) isn’t well known.

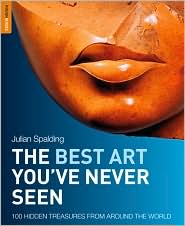

The Best Art You’ve Never Seen isn’t an exhibition, though; it’s a book, by one Julian Spalding, a former museum director in Britain. It was published late last year, but I just came across it recently (it hasn’t had much recognition here, at least), and I was intrigued. The subtitle is 101 Hidden Treasures from Around the World. Fittingly, the publisher is

The Best Art You’ve Never Seen isn’t an exhibition, though; it’s a book, by one Julian Spalding, a former museum director in Britain. It was published late last year, but I just came across it recently (it hasn’t had much recognition here, at least), and I was intrigued. The subtitle is 101 Hidden Treasures from Around the World. Fittingly, the publisher is