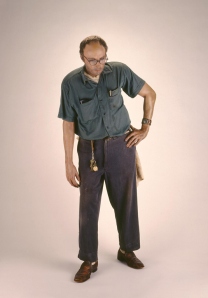

Surprise: Britain’s annual giving list places an artist — David Hockney — at the top of the roster for 2011.

The list, published by the Sunday Times, calculates rank based on the amount of wealth given away as a proportion of overall income, not on absolute value. But Hockney does well on either score, if you allow for the fact that his gifts were of his own art. He gave away £78.1m worth of paintings to charitable causes, which is more than double his estimated £34m wealth.

The list, published by the Sunday Times, calculates rank based on the amount of wealth given away as a proportion of overall income, not on absolute value. But Hockney does well on either score, if you allow for the fact that his gifts were of his own art. He gave away £78.1m worth of paintings to charitable causes, which is more than double his estimated £34m wealth.

Hockney also gave away £730,000 in cash through his David Hockney Foundation, whose website is currently under construction. A listing for it at Charities Direct, however, says that it was founded in 2008 with a goal of “The education of the public in the appreciation of art and in particular the creative art of today.” Its “total funds” as of December 2010 were £77.51m.

What I could not determine was how values were placed on Hockney’s gifts — and by whom.

Hockney’s recent exhibition at the Royal Academy, which led to a dispute over what art is with Damien Hirst, did well, according to one of the reports on the philanthropy rankings — before closing on Apr. 9, it attracted more than a half-million visitors and featured some works that belong to the foundation. Which raises another question — of those assets (total funds), how much is art? Will he sell any to put cash into education of the public?

And the larger question is this: many artists are rich nowadays. Are others actively giving away money?

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Third Sector